Rigoberto Uran climbs into contention at Montasio (photo courtesy SHIFT Active Media and the RCS Sport cycling press office)

At the beginning of the Giro it seemed as though Stage 10 would be the first day where a clear road order would emerge. The climb of Montasio was going to give us a chance to see which of the favourites were up to the task of challenging for overall honours. However, an exciting first week provided us with a good indication of what would happen on the first mountaintop finish of the race.

Bradley Wiggins found himself in difficulty descending in the wet on several stages, and gained only a small amount of time on his rivals in the individual time trial. It is unclear if Wiggins’ difficulties were a sign of form, illness, or injuries due to crashing on Stage 7.

Defending champion Ryder Hesjedal began the race in impressive style, with an unexpected attack on just the third day of racing. Optimism turned to worry as he lost significant time to all major rivals during Saturday’s time trial, and was dropped from a group of thirty the following day.

Of the three main favourites at the beginning of the race, it is the man in Pink, Vincenzo Nibali who has been most impressive. At no time has Nibali looked in difficulty, and his ITT performance makes him a clear favourite to win the general classification.

The first mountain challenge proved to be a continuation of the order which had established during the first week. Hesjedal had been dropped on Sunday, but no one could have predicted what happened on Stage 10. The Canadian lost contact with the main group on the penultimate climb of the day, and was not seen again until the finish. This is no minor struggle with form; Hesjedal is clearly not on the same level as he was in 2012. For the sake of our analysis, Hesjedal is out of the picture.

Early on the final climb, Rigoberto Uran attacked out of the main group. The initial reaction from the bunch was subdued and a genuine reaction would not come until the closing kilometres. Wiggins did not make the final selection which formed on the steepest part of the climb. Uran won the stage, with Nibali the strongest of the main favourites at 31 seconds. Wiggins finished more than one minute behind his teammate.

|

Stage 10 Result |

|||

|

1 |

URAN Rigoberto | 4:37:42 | |

|

2 |

BETANCUR Carlos | 20″ | |

|

3 |

NIBALI Vincenzo | 31″ | |

|

4 |

SANTAMBROGIO Mauro | 31″ | |

|

5 |

EVANS Cadel | 31″ | |

|

6 |

MAJKA Rafal | 31″ | |

|

7 |

POZZOVIVO Domenico | 31″ | |

|

8 |

KISERLOVSKI Robert | 47″ | |

|

9 |

INTXAUSTI Benat | 1’06” | |

|

10 |

WIGGINS Bradley | 1’08” | |

|

… |

… | … | |

|

71 |

HESJEDAL Ryder | 20’53” | |

The climb began in earnest from the 10.61km to go mark, with 859m of vertical gain at a gradient of 8.09%[1]. From this point it took Uran 31 minutes and 15 seconds to reach the finish line.

|

Montasio |

Time |

VAM |

|

|

1 |

URAN Rigoberto | 31’15” |

1649 |

|

2 |

BETANCUR Carlos | 31’35” |

1632 |

|

3 |

NIBALI Vincenzo | 31’46” |

1622 |

|

4 |

SANTAMBROGIO Mauro | 31’46” |

1622 |

|

5 |

EVANS Cadel | 31’46” |

1622 |

|

6 |

MAJKA Rafal | 31’46” |

1622 |

|

7 |

POZZOVIVO Domenico | 31’46” |

1622 |

|

8 |

KISERLOVSKI Robert | 32’02” |

1609 |

|

9 |

INTXAUSTI Benat | 32’21” |

1593 |

|

10 |

WIGGINS Bradley | 32’23” |

1592 |

Earlier in May I used a data set of Hesjedal, Nibali and Wiggins to predict the time it would take for the favourites to complete the Giro’s climbs:

| Gradient | Vclimb | Altitude |

pVAM |

pTime |

90% CI | |

| Montasio |

0.0809 |

859 |

1519 |

1658 |

31’05” |

29’27” – 32’54″ |

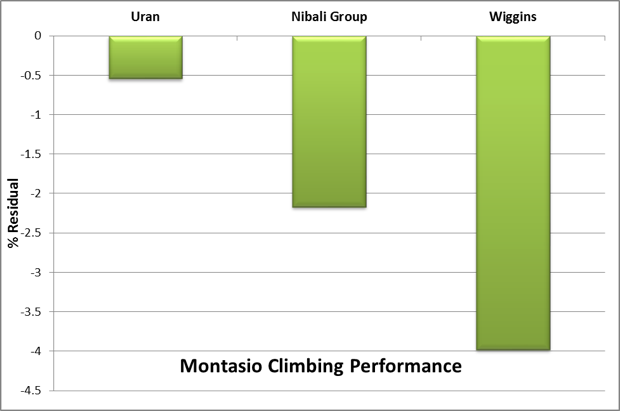

Uran was only ten seconds slower than predicted, with Nibali and Wiggins slower by 41” and 1’18” respectively. In terms of the percentage deviation from predicted VAM, Nibali was -2.2% and Wiggins -4%.

The performance of Uran is more impressive than the results indicate, given that he spent more than three quarters of the climb alone at the front without the advantage of drafting. This is Wiggins’ worst climbing performance in the last 12 months (excluding his Trentino mechanical). In the 2012 Tour, the lowest residual was -0.9% for both Wiggins and Nibali. Nibali may have held something back, content to just mark his rivals. The leader of the race also had a minor mechanical issue in the final kilometre which may have cost him a few seconds. In any case, the two percent difference is well within the range we would expect. Wiggins’ on the other hand was clearly performing at his limit; his lacklustre showing can only be explained by illness or injury. If that is not the case, his form is simply not as good as it was last year.

One result is far from enough to make general conclusions about the condition of riders. All riders were marginally slower than expected and this may be more a reflection of the tactics on the Giro’s first MTF than a definitive example of the limits of the race’s overall contenders. We look forward to the weekend, where summit finishes at Jafferau and Telegraphe-Galibier should provide further evidence of how well the best riders are climbing.

Editor’s note: We’re very pleased with the way the pVAM equation is performing so far in predicting climbing performances, and are hopeful it will give us the ability to do a much more insightful analysis when comparing riders’ efforts than anything previously seen. Look for a new analysis piece here on Cyclismas after each climbing stage. By the end of the Giro we hope that readers will have a better understanding of Scott’s pVAM method. By the time the TDF rolls around hopefully it becomes the go-to source for performance analysis. A huge thanks to Scott Richards and Mike Puchowicz, better known as Doc @Veloclinic, for all their work on this.

[1] The official profile was slightly inaccurate so the data has been updated to reflect the actual length of the climb.

2 Comments

[…] began in earnest from the 10.61km to go mark, with 859m of vertical gain at a gradient of 8.09%[1]. From this point it took Uran 31 minutes and 15 seconds to reach the finish […]

[…] began in earnest from the 10.61km to go mark, with 859m of vertical gain at a gradient of 8.09%[1]. From this point it took Uran 31 minutes and 15 seconds to reach the finish […]