Eddy Merckx has recently been inducted into the Giro d’Italia’s newly established Hall of Fame. The corsa rosa is a race he won five times between 1968 and 1974. Had it not been for the inconvenient presence of a prohibited substance in a urine sample during the 1969 Giro, it would have been six.

The Belgian champion Eddy Merckx is the first rider to be inducted into the newly-formed Giro d'Italia "Hall of Fame."

Before there was Marco Pantani and Madonna di Campiglio, before there was Michel Pollentier and the Alpe d’Huez, there was Eddy Merckx and Savona. The first Grand Tour leader to be turfed off a race under a cloud of controversy caused by doping.

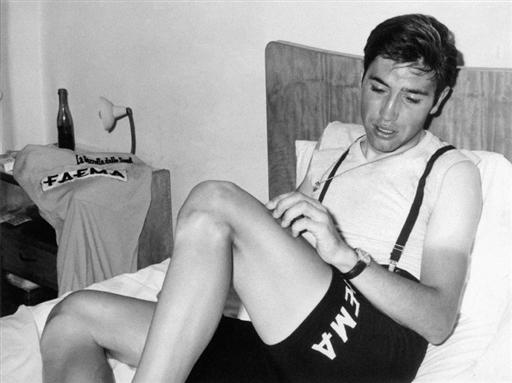

On the morning of Monday, June 2, 1969, Eddy Merckx was in his room in the Hotel Excelsior in Savona on Italy’s Ligurian coast. He and his room-mate Martin van den Bossche were passing time before the start of a stage due to take the Giro to Pavia. Following a rest day and a transition stage from Parma the Giro was warming up for its final Act, a few days in the high hills before the grand finale in Milan, where Merckx’s second victory in the corsa rosa seemed as sure as a sure thing. Thoughts were already turning to the Tour de France. Could Merckx beat the grande boucle into submission, join Fausto Coppi and Jacques Anquetil as the only men to have won two Grand Tours in the one year, done the Giro/Tour double? Not after Savona he couldn’t.

Vincenzo Giacotto, the Faema direttore sportivo, entered Merckx’s hotel-room, along with Vincenzo Torriani, the Giro’s direttore di corsa. With them came a TV camera crew and two journalists, Théo Mathy (a Belgian) and Bruno Raschi (an Italian). It fell to Giacotto to break the news to Merckx: busted. The media duly recorded the maglia rosa‘s reaction: shock, followed by disbelief, denials, and tears.

A sobbing Eddy Merckx on the day he was kicked off the Giro in 1969 (Photo © AFP Photo courtesy cyclingnews.com)

Eddy Merckx’s expulsion from the 1969 Giro d’Italia was more than just a personal tragedy, more than just a sporting tragedy: it became a diplomatic incident, with Belgians and Italian’s facing off and questions being asked in parliament. On the sporting side of the issue, not only was Merckx denied a second victory in Italy but, by virtue of the immediate one-month suspension he was handed, he was also about to be denied his début at the Tour de France, a Tour which had been planned with him in mind, passing as it did through his home town of Woluwe-Saint-Pierre on the outskirts of Brussels.

In 1969 the UCI’s fight against doping was in its infancy. Belgian and French legislators had landed the first blow with national legislation in the mid-sixties. Following the death of Tom Simpson in 1967 – and the less widely reported death of Roger de Wilde – the fight was supposed to be being conducted with new vigour and a clear determination to root out the problem of drugs in sport. The early testing, though, was limited in its effectiveness, barely capable of spotting amphetamines let alone some of the hardcore arsenal of doping products several riders steeled themselves with. But almost as ineffective as the testing itself was the manner in which punishments were meted out: some riders were treated with more leniency than others. It therefore came as little or no surprise when a diplomatic solution to the problem of Merckx’s positive test was arrived at.

The diplomacy of the solution was not simply about repairing relations between Belgium and Italy. It was about balancing the needs of various members of the cycling establishment. The organisers of the Giro d’Italia, and the Italian cycling federation itself, had to be seen to have done the right thing in expelling Merckx from the Giro. The organisers of the Tour de France had to be accommodated and allowed to have Merckx make his first appearance at their race. And the UCI – both through itself and through its professional arm, the FICP – had to be seen to have done the right thing.

In arriving at a diplomatic solution to the problem, the sport was probably helped by the fact that Adriano Rodoni not only headed the UCI but also the Italian cycling federation, and that Félix Lévitan wasn’t just the to co-director of the Tour de France but was also the chairman of the FICP. Within two weeks of Merckx’s exit from the Giro, the bigwigs of the UCI and the FICP met – in, of all places, Brussels – and arrived at a solution that was elegant in its simplicity: the results of the Savona test were upheld and the decision to expel Merckx from the Giro was accepted but Merckx’s one-month suspension was immediately lifted, the rider being given the benefit of doubt, the fact that he’d never tested positive before being ample evidence of the fact that he couldn’t possibly have knowingly doped.

(That ‘not knowingly doped’ is a wonderful cycling circumlocution, a conscience wet-wipe which more often means that it was the soigneur what did it. It was Richard Virenque’s defence, that Willy Voet had doped him without his knowledge. It was Louison Bobet’s defence, that Raymond le Bert had doped him without his knowledge. And, in at least one telling of the Savona story, a Faema soigneur – a temporary replacement for the absent team doctor Enrico Peracino – did soon depart the team after the dust had settled on the affair. But if he was just a temporary stand-in, then of course he was going to soon depart the team.)

Were the UCI today to say that Alberto Contador or Floyd Landis should have been given the benefit of the doubt because they’d never been caught doping before – were the UCI to have a rule that said you had to be caught twice before real action would be taken against you – they’d be laughed off the stage. But in 1969 the UCI could get away with such things. Actually, the UCI could get away with such things until the advent of WADA in 2004. After Savona, the penalties for being busted – which had been introduced in November 1967, a response to the incident on the Ventoux – were swiftly changed and the initial one-month suspension was itself suspended, not coming into force unless a rider got busted a second time.

Merckx was, in case you’re curious, the only rider caught doping at the 1969 Giro. A month later, at the Tour de France, Rudi Altig (Salvarani), Bernard Guyot (Sonolor), Pierre Matignon (Frimatic), Henk Nijdam (Willem II), and Joseph Timmermann (Willem II) all got busted. Whereas the Giro was testing up to five riders a day – the first two stage finishers, the maglia rosa, and two riders chosen at random – the Tour chose to test three: either the first three on the stage, the first three on GC, or three riders chosen at random. Which group of riders was required to piss into a cup each day was decided in secret by Pierre Dumas, the Tour’s doctor and a champion of the fight against doping, before the Tour got underway. The rules already having been rewritten, Altig and the others suffered no more than time penalties, their suspensions left hanging until the next time they were caught (unless they timed out before then – which was the other elegant part of the UCI’s early fight against doping. Not only did you have to be busted twice in order to suffer a suspension but you had to be busted twice within two years. Or, after Kim Andersen tripped a lifetime ban, one year).

* * * * *

As already mentioned, back in 1969 the UCI took a rather laissez-faire approach to the handing out of doping penalties, some riders being treated with more leniency than others. Merckx’s treatment needs to be seen in the context of the time. He wasn’t the first star the authorities had dealt a get-out-of-gaol-free card to in those days.

At the 1966 World Championships Jacques Anquetil (France/Ford France), Rudy Altig (West Germany/Salvarani), Gianni Motta (Italy/Molteni), Italo Zilioli (Italy/Sanson), and Jean Stablinski (France/Ford France) had all refused to be tested after the race, and Raymond Poulidor (France/Mercier) had claimed to have got lost on his way to the contrôle anti-dopage. The one-month suspensions they each received were quickly overturned and Altig got to keep his rainbow jersey. Anquetil and Altig had also had suspensions overturned earlier in 1966 – the Frenchman after Liège-Bastogne-Liège, the German after Flèche Wallonne – where they had each refused to be tested after their victories. And Anquetil again got away with it at the GP des Nations, where he publicly admitted he had doped but was again not suspended, here as a “gesture of mercy” and in recognition of “the great honour bestowed on international cycle sport, to wit his Légion d’Honneur.” (In fairness to the UCI, Anquetil didn’t get away with it in 1967, after he refused to be tested following his Hour record ride. His punishment then was the UCI’s refusual to ratify the new record.)

And then there was the 1968 Giro. All told, that edition of the corsa rosa produced eight positives (Peter Abt/GBC, Raymond Delisle/Peugeot, Gianni Motta/Molteni, Franco Bodrero/Molteni, Franco Balmamion/Molteni, Joaquim Galera/Fagor, Mariano Diaz/Fagor, and Felice Gimondi/Salvarani), two attempts at fraud (Vittorio Adorni/Faema and Victor van Schil/Faema), and one failure to supply a sample (Mario di Toro/Kelvinator – he was actually hospitalised at the time, after a crash). With four previous winners on the list of offenders – Balmamion (1962/63), Adorni (1965), Motta (1966), and Gimondi (1967) – questions had to be asked. Not one of those questions was asked during the Giro, though, as none of the positives were revealed until after the race was over.

All the Giro positives had been for amphetamines. Gimondi and Van Schil argued that they’d actually used the same fencamfamine Merckx would be busted for a year later, which – though, it had amphetamine-like effects – wasn’t on the banned list (yet). Better still, Gimondi claimed that the drug had been recommended to him by a senior member of the Italian fed. This was denied, Gimondi had merely been advised that the drug wasn’t on the banned list. Some of the other riders – including Balmamion – also had their bans overturned. Others saw their guilty verdicts upheld and – in the cases of Motta and Bodrero – their stage victories stripped from them. Because of the events at the Giro, Gimondi and Motta both missed the chance to ride the 1968 Tour.

Looking at those precedents, whether you agree or not with the findings of the dope testers at Savona, you can understand how a rider of Merckx’s stature might have felt that the rules were being applied unfairly against him. But one should also look lower down the food chain and consider some of the riders whose doping positives – and concomitant suspensions – were upheld. Jean Stablinski, Jan Janssen, and Lucien Aimar had each served their time off having been busted, Stab at the ’68 Tour, Jandsen at the ’69 Paris-Nice, Aimar at the same Paris-Nice and again at the Critérium National. If – as seemed to be the case – it was one rule for the grands coureurs and another for the little men then, Merckx must have felt like he had just been handed the biggest insult of his career: he was too small to be worth saving. Slice it, dice it, cut it whatever way you care, but one way or another Merckx had good reason to feel he was being treated unfairly, whether he was guilty or not.

* * * * *

All sorts of stories have been told and retold, dozens of questions asked, about what really happened at Savona. The number and variety of possible explanations for Merckx’s positive – everything bar the possibility that Merckx had actually doped – puts the imaginations of the likes of Tyler Hamilton and Floyd Landis to shame.

There’s the story of the suitcase of money Merckx had been offered on the rest day, the day before the Savona test was carried out, payment to throw the race in favour of an unnamed Italian rider but which the Belgian had turned down. Had that refusal led someone to eliminate Merckx by other means? Or was it a stitch-up by others, fed up with Merckx’s processional ride and his failure to share and share alike when it came to stage victories, both in 1969 and during his 1968 ride to victory?

There’s the story of the mobile testing laboratory sponsored by Hewlett-Packard and used by the Giro organisers to produce timely results and avoid the embarrassment of the previous year when the guilty weren’t identified until after the race was over. As well intentioned as that mobile lab was, it was – apparently – against the UCI’s own rules, which only mandated laboratories in Paris, Rome, and Ghent to carry out doping analysis. And didn’t those same rules also require the A and B samples be tested in different labs? Even if the HP lab and its analysis were legit, could the results really be relied upon, wouldn’t all those miles over Italy’s poxy road network have damaged the sensitive testing equipment? Could the testers themselves – i.e., Angelo Cavalli, who himself went on to become Merck’s doctor at Molteni, where he took the fall for the Belgian’s positive at the 1973 Giro di Lombardia – be trusted, bearing in mind that they were in daily contact with the riders and team personnel? Intimidation at other races was already a fact of life, why not at that Giro too?

There’s the story of the B sample being tested without anyone informing Merckx or his team of the results of the A test. Was the presence of Professor Genovese, the riders’ medical representative on the Giro, really sufficient to lend credence to such testing procedures? There’s the story of the mis-labelled doping sample, a six read for a nine (or was it the other way round?). There’s the story of the poor procedures for storing doping samples, the chain of custody a joke even when compared to the alleged faults in the testing of Floyd Landis’s 2006 Tour samples.

There’s the story of the mysterious bidon which a priest said miraculously appeared on Merckx’s bike while he was praying before the start of the stage to Savona: had Merckx been stitched up, slipped a Mickey Finn? Or had the Mickey Finn been passed up from the roadside, an innocent bottle of water passed from tifiso to champion-elect laced with the easily available Ritalin that would have produced a fencamfamine positive?

There was the question of what sort of fool did people take Merckx for, he was wearing the maglia rosa, knew he’d be tested. Hadn’t Merckx sailed through the eight other tests he’d been subjected to during the race, how could he possibly be guilty on the ninth? The stage from Parma to Savona had been inconsequential, so why would Merckx have bothered doping for it?

There was the question of how – apparently – some teams had known of Merckx’s positive the night before when it was after ten in the morning before Merckx had been informed of it and the first test had only been completed six hours earlier.

There was the question about the coincidence in the fact that the stage to Savona had started in Parma, the home town of Faema’s great rivals in the Salvarani squad. Follow the money – look to who gained the most by Merckx’s expulsion from the Giro – and you end up back in Parma and the Salvarani HQ, where Felice Gimondi’s victory was celebrated.

There was the question of whether Merckx’s positive was connected to the rumours in circulation before the commencement of the race, rumours which said Merckx wouldn’t make it to Milan.

There were the inevitable questions about the identity of the doer of dirty deed. Was he a traitor within Merckx’s Faema camp? Was it the disgruntled soigneur soon set to leave the team? Was it the teammate already tired of playing second fiddle to the maestro?

There was the question of why Vincenzo Torriani hadn’t simply buried Merckx’s positive. Was he really willing to risk damage to his own race in order to deny his rivals in the French tour the much anticipated début of the new hero of cycling?

And then there was the second, unofficial sample Merckx provided after the news of his positive was broken to him. How, if the concentration of fencamfamine was as high in the Savona sample as the experts declared, had all sign of the drug disappeared when that second sample was tested? To whom did that second urine sample really belong, Merckx himself or a publicity-stunt double? Did that second test actually take place or was the result fabricated to feed the media monster?

Questions, questions, questions. Answers came there none. To this day, Savona ’69 remains a riddle wrapped in a major fuck-up tied up in a dozen different conspiracy theories, all hiding a simple truth. A lot of people claim to know that truth. But none of them are speaking it publicly. The secret of Savona is in safe hands.

To this day, Merckx himself insists he was innocent and wronged at Savona. If the UCI gave him the benefit of the doubt shouldn’t we? Perhaps we should. But scroll forward a few years from Savona. Pass that second bust at the Giro di Lombardia, the one for which Cavalli took the fall, and instead pause on Merckx’s third strike: the 1977 Flèche Wallonne, where Stimul was found in his sample. For a third time Merckx protested his innocence:

I do not believe any more in these controls; it is all becoming ridiculous and hypocritical. I haven’t even asked for a second analysis. I am going to make a list of all that is wrong with these controls. As things are nobody could have confidence in them.”

Indeed. A familiar refrain. Familiar down to the fact that Merckx did eventually admit that yes, he too had used Stimul, just like the vast majority of the peloton at the time. Merckx even talked of the times he and one of the De Vlaemincks had fooled the dope testers. Only to change that story yet again in later years and insist he had never used anything stronger than vitamins.

After that, all you have to do is decide for yourself which version of the truth you want to believe.

Up next: Part two of the Merckx marathon continues with Merckx 69: the birth of “The Cannibal.”

* * * * *

Sources: Both of the recently released biographies of Eddy Merckx cover the Savona affair in considerable detail: Eddy Merckx – The Cannibal, by Daniel Friebe (Ebury Press, 2012, 344 pages); and Merckx – Half Man, Half Bike, by William Fotheringham (Yellow Jersey Press, 2012).

The Savona affair is also covered in the three Giro d’Italia-related books released last year: Maglia Rosa – Triumph and Tragedy at the Giro d’Italia, by Herbie Sykes (Rouleur, 2011, 312 pages); Pedalare! Pedalare! – A History of Italian Cycling, by John Foot (Bloomsbury, 2011, 372 pages); and The Story of the Giro d’Italia – A Year by Year History of the Tour of Italy, Volume I, 1909-1970, by Bill and Carol McGann (McGann Publishing, 2011, 309 pages).

4 Comments

[…] But no, 1969 was not the year he did it. He did come close – a cat’s whisker close – but in 1969 Eddy Merckx was turfed off the corsa rosa a week out from home, with four stage wins under his wheels and the maglia rosa on his back. Cycling’s fickle […]

[…] to notice the symbolism of the gladioli to be found in the hotel reception that Monday morning in the 1969 Giro, or drop in comedy moments like Roger de Vlaeminck demonstrating how to mop up spilled coffee […]

[…] Let’s talk doping. Let’s talk Savona. Almost everyone who was there – and quite a few people who weren’t – seems to claim to […]

[…] in ’69, ’73 and ’75 (in the latter 2 cases he blamed the doctor, in the first, he blamed Italy – well, kind of, and a diplomatic row ensued). when Armstrong announced his decision not to […]