“Honest people don’t hide their deeds.”

~ Emily Brontë

There’s a scene in Mark Johnson’s Argyle Armada that, for me, just about sums up what’s so cool about Jonathan Vaughters’ Garmin. It’s not a scene that’s unique to Garmin, you’ll see it all the time in this strange sport of ours. And it’s a scene that appears, in modified forms, throughout Argyle Armada, at races in France, in America, in Canada. The repetition of the scene probably helps explain why some people like the team that Doug Ellis bankrolls and which Jonathan Vaughters has built. And helps explain why we like the sport of cycling.

This particular scene happens to be set in Belgium. The Garmin-Cervélo boys – Ryder Hesjedal, Christophe Le Mével, Dan Martin, Peter Stetina, and Christian Vande Velde – are out for a pre-ride of the final hundred kilometres of the Liège-Bastogne-Liège course, the Friday before the 2011 La Doyenne rolls off. Behind them in the team-car are directeur sportif Eric van Lancker and wrench-monkey Alex Banyay, Johnson riding along with them and taking it all in.

Van Lancker is pointing out things, the psychogeography of the region: the Côte de Wanne where, traditionally, the peloton gets cut down to size; the Col du Maquisard just outside Spa where a truck once lost its brakes and thrashed a house; a filling station just outside Sprimont, over La Redoute, where he himself broke away for his Liège victory in 1990; the Côte de Stockeau where so many decked it during the 2010 Tour de France. Every inch of the road has some memory attached to it, some ghost image shadowing it.

Up front, the guys are just riding along. All at once, a gang of kids rush out of a yard screaming for a bidon to be tossed to them. Vande Velde duly obliges with a souvenir. Then, on a climb near the end of their ride, there’s a small kid riding along on the pavement. The wee runt can’t even be a teenager yet but he’s decked out in full racing kit. And when he sees the Garvélo boys pass, the competitive juices kick in: he bunny-hops his little racing bike onto the road and gives chase to the pros in front.

Christophe Le Mével looks around and shouts encouragement at the kid – ‘Allez, allez!‘ – and the kid digs in. Then, after a few hundred metres, he falters and falls back. Rather than just riding on, Le Mével sits up and waits for the kid to ride up to him. Placing himself on the kid’s outside the Frenchman puts his hand on the lad’s back and takes him to the top of the climb. There he pulls a bidon from its cage and hands it over. Johnson’s back in the team car, doesn’t hear if any words are exchanged, but the sentiment is clear: ‘Chapeau you little brat, you deserve it.’ Then the Garvélos get back to the business of preparing for Sunday and the kid is left to ride on alone.

Which is that little kid’s biggest souvenir of that day, the bidon given to him or the memory of Le Mével’s hand on his back?

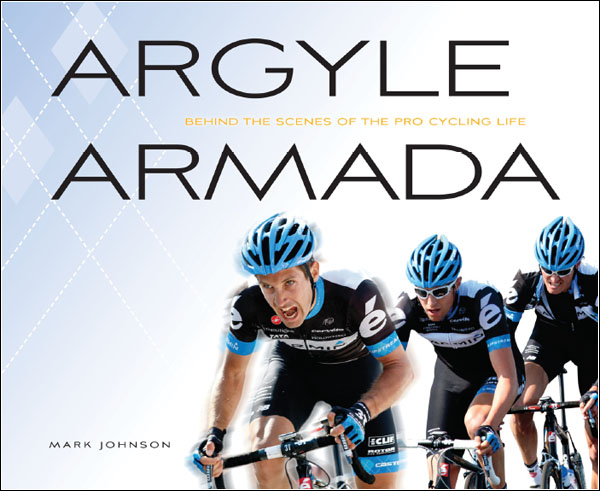

Argyle Armada is a look behind the scenes of pro cycling life, through the lens of a freelance writer and photographer who’s worked with the Garmin team since 2007. That Johnson is a photographer might make you think that Argyle Armada is another coffee-table photo album, but there’s a lot more to it than that. Before getting into the book itself, let’s try and look at it in the context of other cycling books.

One could look to some of the books written about Lance Armstrong – here, particularly Daniel Coyle’s Lance Armstrong’s War or Bill Strickland’s Tour de Lance – which, through the privileged access the authors were given over the course of a particular season, ended up being partly about the team as well as the rider. Or one could look at something like Jeff Connor’s Wide-Eyed and Legless, which is fully about one team, but just for one race, there the ANC-Halfords squad in the 1987 Tour de France. For me, the book that has most in common with Argyle Armada is Richard Moore’s Sky’s the Limit, the story of Team Sky’s début season, 2010.

But, whereas Moore’s book was words with a few images inserted in the middle, Johnson’s tells its story through words and pictures. Most of the photographs are illustrative: you can flick through it as a coffee-table photo album and a few of the pictures will jump out at you and make you pause. But, as you work through the text, you realise that the images are really there to add depth to what Johnson is saying. The words and images work together synergistically.

Generally having avoided coffee table photo albums in the past (for no particular reason) I asked Johnson himself what model he had in mind when putting the book together:

What I had in mind was a series of New Yorker–like day-in-the-life chapters that were illustrated by photographs. Because there is so much political, social, and economic import to what Jonathan Vaughters is trying to do with this team, I had no interest in doing a photo-only book with captions.”

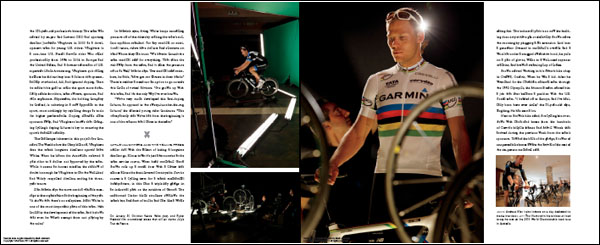

The pictures used in Argyle Armada are an important part of the package, and you’ll find selections from them on the book’s website, ArgyleArmadaBook.com. But, as well as painting pictures with light and shade, Johnson – who has a Ph.D. in English literature from Boston University – also paints pictures with words. Take some of these images: orange-shirted fans on a rock promontory peering into a valley’s profundity; fans cheering a rider up a climb and looking like thousands of agitated cilia urging a blue egg up a nine-mile trench of humanity; ossified sticks protruding from the muck and a scudding mist giving the place the feeling of a primordial graveyard; a ridge sprinkled with the confetti of fans’ camping tents; weak sunlight inscribing a rim of light around a pain-wracked visage; lurid light tracing the cheekbones of a gendarme; riders sibilating down serpentine descents. My own use of the English language may tend toward the more base end of the spectrum but there is something pleasing in seeing cycling described in such language.

An obvious antecedent to Argyle Armada that I should mention is the series of articles Paul Kimmage wrote for the Sunday Times about the team’s 2006 Tour and which can be found in the most recent (2007) edition of his Rough Ride. Kimmage himself crops up a few times in Argyle Armada. At the Tour, Johnson bumps into him and Kimmage explains how and why he has to stop himself from returning to the Garmin bus, force himself to talk to others: “Why I like these people is that they are decent human beings. They are all good people, and I cannot say that about a lot of others.”

Oddly, that inability to say the same of others as he can of Garmin does not endear Kimmage to everyone in the Garvélo team. Andrew Talansky tells Johnson that, while it’s great that his team gives the Irish journalist hope, he personally believes that “somebody like him has no place in the sport of cycling and doesn’t deserve to write about it.” Oddly, I actually like Talansky for having that opinion. I disagree with him, that should go without saying, but that Talansky can and does say it – that I like and admire. And, as Johnson found from different riders on different topics, while they all sing from the same hymn sheet on doping, on other issues – from race radios through to internal team politics – they have and express their own opinions. They’re a tightly knit team but they’re also individuals.

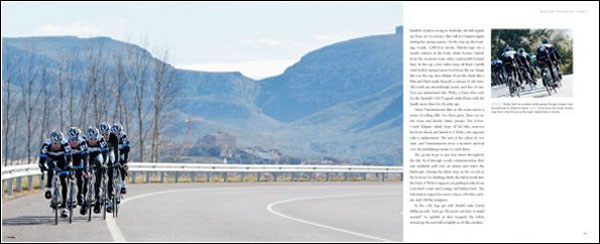

The picture of the team painted by Johnson is broader than that drawn by Kimmage in 2006, not just through his use of photographs but also by his looking beyond the Tour de France. Argyle Armada isn’t a full account of Garvélo’s 2011 season, but does cover a large chunk of it. Johnson was with the team at their January/February winter training camp in Girona, then met up with them again for the cobbled Classics (the Ronde van Vlaanderen, Scheldprijs and Paris-Roubaix), and then again in the Ardennes (the Amstel Gold, the Flèche-Wallonne and Liège-Bastogne-Liège). From there it was westward ho and a trip to the Tour of California, followed by a trip back across the Atlantic for the Tour de France. After that came the USA Pro Cycling Classic and the latter part of the Vuelta a España, whose opening clashing with the Colorado race necessitated Johnson missing the first part of the Spanish Grand Tour. Johnson also had to skip out before the end of the Vuelta in order to wrap up his road season in Canada, with Serge Arsenault’s two contributions to the World Tour calendar (the GP Cycliste de Québec and the GP Cycliste de Montréal). Johnson then rounded out the season with the preparation for the 2012 team’s coming out party in Boulder in November.

Having pointed out that Johnson has been a freelancer with the Slipstream outfit for some time now I should probably disclose my own interests – prejudices – here. Not whether I blagged a review copy of the book (ask William Fotheringham, Geoff Drake, Nicolas Roche, or David Millar if they think that affects how I read a book) but that I am a fan of Jonathan Vaughters and a fan of his Garmin team. Some of that, I will openly admit, is purely parochial: Dan Martin rides for them and, like most cycling fans, I too can fly the flag for my own countrymen. Mostly, though, I’m a fan because I want to believe in what Vaughters is trying to do: clean up our sport, ethically and structurally. And because Garmin are fun.

Do you have to be a fan of the team to like Argyle Armada? I don’t think so. Part of my reason for saying that is because when Johnson is talking about individual Garvélo riders and the races he witnessed, he’s telling human-interest stories, universal stories. The other part is that, while Garvélo are the lens through which Johnson looked at the 2011 cycling season, the book isn’t really about them. It is, as its subtitle claims, a behind-the-scenes look at the pro-cycling life.

Liking Garmin, though, does add an extra edge to Argyle Armada. This was the year that the little team that could, the team that traded on their ethically-clean image more than their palmarès, grew up. Not just in the way they added lustre to their palmarès with Paris-Roubaix, stage wins, and leaders’ jerseys in all three Grand Tours and the rest. But in the way they shed their skin, lost some of their sheen.

Johan Vansummeren wears the crushed embers of the Hell of the North as he celebrates his victory in the Queen of the Classics. Source: Mark Johnson

From the dismissal of Matt White at the start of the season through to the folding of the women’s team at the end of the year, 2011 was the year Garvélo really felt the wrath of fans who began to see the team’s innocence disappear before their eyes. Add in the arguments over race radios, boycotts, breakaway leagues, the decisions made about withholding departing riders from certain races in order to stop them taking points across to others, and the Argyle armada began to look like a lot of the other teams out there: merciless, rapacious pirates. It all added up to the team losing some of their USP. Having to grow up. (At the same time, the team still maintains their own quirky, child-like charm: borrowing a fire-red Porsche during the Tour of California, sticking a roof rack on it and using it as the team car for the day is the sort of fun Vaughters and his bunch of lost boys bring to the peloton, and long may they continue to do so.)

The business of pro cycling filters throughout Argyle Armada and is, for me, something that makes Argyle Armada an important book for all who are curious about what is going on behind the scenes in cycling. Johnson himself tries to express no particular opinion, tries to get others to say what needs saying. Like most of us, he does agree that our sport needs to change, but he’s not using Argyle Armada to prescribe what that change should be. On one particular area he does let his own feelings filter through: the need for someone to come in, grab the sport by the scruff of the neck, and drag it kicking and screaming into the twenty-first century.

On this topic Johnson is particularly influenced by something that happened in baseball half a century ago. A lot of the time when we talk about the business of pro cycling we end up talking about other sports, looking to other sports – as they too look to one and other – to see what works and is worth borrowing from. Back when Hein Verbruggen was first throwing his weight around in the FICP he wanted to model cycling on tennis’ ATP Tour. Thus was born the World Cup, the successor to the Super Prestige Pernod trophy and the precursor to the ProTour and today’s WorldTour (the difference between the ProTour and the WorldTour is the same as the difference between Windscale and Sellafield: none). Today, rather than looking to tennis, many people want to model cycling on Formula 1. Baseball though is growing in popularity as the sport to look to.

Here I’ll again turn back to Richard Moore’s Sky’s the Limit and note his use of Michael Lewis’ Moneyball, a book referenced to him by Team Sky supremo and über-statto Dave Brailsford. Moneyball told the story of how Billy Beane took a little team of sluggers and challenged the big boys by turning to objective, empirical data when selecting new recruits for his team. More importantly the story of Moneyball was how an insider successfully brought outsider thinking into his sport. Moneyball does feature in Argyle Armada – the Brad Pitt film rather than the Michael Lewis book – but the baseball story Johnson most turns to is that of Marvin Miller.

Back in the 1960s Miller, who was a big shot in the United Steelworkers Union, threw his weight behind baseball and organised a players union, through which the men in the funny pyjamas were able to negotiate a slice of TV revenues and other image rights. This question of unionisation – and the need for a Marvin Miller to step forward in cycling – is something Johnson talks to various riders about. (The riders today do have a union, the CPA, but that’s about as useless as a eunuch in a brothel, and for the same reason: it lacks balls.) Each time, Johnson gets the same answer: not going to happen. None of the riders seem happy about this, but they are realists. Others can too easily play divide and conquer when it comes to the peloton. As Dan Martin tells Johnson, within the peloton “there’s always someone trying to get one over on someone else.”

Baseball is also the sport turned to by Jonathan Vaughters to explain what cycling needs to do, and not do. He himself uses a similar approach to Moneyball‘s Billy Beane when selecting new recruits for the team, but he also looks beyond the stats to find riders who are going to fit in with the ethos of his team: not just the clean living approach to cycling, but the fun-loving side of a project he’s been building since his 5280 and TIAA-CREF days. “What I’m looking for,” he tells Johnson, “is smart guys that may be a little bit goofy, because a lot of times intelligence goes hand in hand with goofiness, especially with bike riders.” The use of stats aside, what’s most important about baseball for Vaughters is the shared history and thinking that sport has with cycling.

Baseball and cycling are – give or take a few years – of similar vintage: both sports were created in the latter part of the nineteenth century. Back in the days of Bobby Walthour and Major Taylor the two sports challenged one and other for the hearts and minds of American sports fans. Cycling initially held the upper hand but, after the NCA broke away from the LAW, baseball pulled ahead. Then, in the 1920s, baseball suffered from the fallout of the Black Sox scandal and lost some popularity, allowing cycling, particularly the Six Day races in Madison Square Garden, to again came to the fore. Baseball, though, immediately learned a lesson that it took the Festina scandal to teach cycling: an outsider, Commissioner Landis, was brought in to put some stick about and make sure that history could not repeat itself. Since then baseball has gone from strength to strength (even when faced with its own doping demons).

The important lesson about baseball, for Vaughters, is how it has managed to move forward and stay still at the same time: despite all the professionalism that has been brought to the sport, all the Marv Millers and Billy Beanes who have pushed baseball forward, it has managed to cling fast to tradition. It is, Vaughters tells Johnson, “still a very quaint, old-fashioned sport. Yet it’s correctly managed.” Players, teams, broadcasters have all been able to grow rich off of baseball’s ability to professionalise itself, while the game itself is, more or less, unchanged. (Fans of baseball might want to argue some of that point, highlight how fans have been fucked over by their sport, but that’s a discussion for another day.)

Is Vaughters cycling’s Marvin Miller? I’m not sure that Johnson is saying he is, and I’m not sure if Vaughters himself sees that as the role he wants to fulfil. Yes, as he tells Johnson, he wants to be the catalyst for change, the man who lit the blue touch paper, but to be the man who brings about that change? Well, with Vaughters you never really know what he’s thinking, do you? Johnson, through his selection of interviewees, does throw up some other names that ought be considered in the Marv Miller role. Doug Ellis, Garmin’s sugar daddy – the biggest littlest team’s version of BMC’s Andy Rihs, RadioShack-Nissan’s Flavio Becca, Sky’s Rupert Murdoch – is one obvious candidate, a man who hides quietly in the shadows, the unseen hand guiding many of the pieces on cycling’s chessboard. Or there’s a race organiser like Serge Arsenault, one of Johnson’s best interviewees. I’d love to tell you more about him here, but he, too, is a subject for another day. Or you could just go and read Johnson’s book yourself and learn a bit more about him.

There are things I would have liked more of in Argyle Armada: more space for the women’s team and the junior team and how they fit into the overall Slipstream structure and ethos; more on the tensions between Jonathan Vaughters and Thor Hushovd; a more complete look at the team’s season. But these weaknesses I understand and have to excuse. The book wasn’t about the women or the kids, it was about the ProTour team. No one anywhere else has really got under the skin of the tensions between Vaughters and Hushovd. The book was never meant to be a complete picture of one team’s season, but rather a look at the sport itself, through moments in one team’s season.

That last point is what is most important about Argyle Armada. Since Festina we’ve managed to get the media to pay more and more attention to doping, forced change to happen within the sport. Now it’s time for the spotlight to shift to the business of professional cycling, time to understand more about how our sport works, understand what does work and what needs to be changed. Argyle Armada is a valuable contribution toward the shifting of that spotlight. Whether you’re a fan of the little team that could – and, in 2011, did – or you just want to understand the politics that are reshaping our sport, Johnson’s is a book you really should read.

* * * * *

Mark Johnson’s Argyle Armada – Behind the Scenes of the Pro Cycling Life is published by VeloPress (2012, 207 pages).

Next up: an interview with Mark Johnson.

2 Comments

[…] the pictures work together synergistically. I tried to compare it with other cycling books in the review, but did you have a particular model in […]

[…] up not just a review but a full exploration of the book Argyle Armada. Spend a few minutes reading this article and you’ll gain a more complete understanding not just of Mark Johnson’s book, but of […]