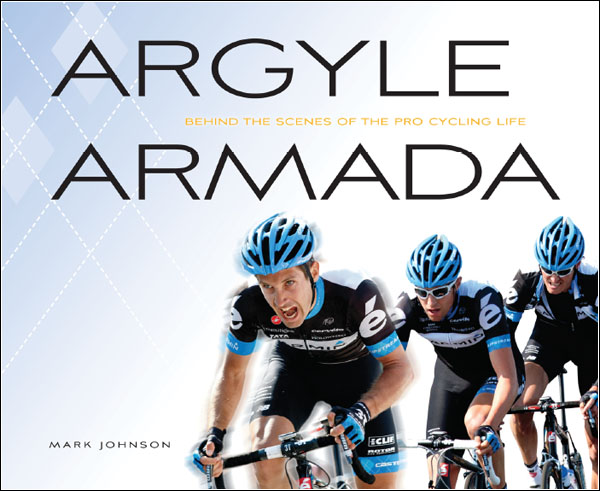

Argyle Armada tells the story of a year in the life of pro cycling, as seen through the lens and words of a photographer and writer trailing the Gamin-Cervélo team for parts of the 2011 season. We put a few questions to the author and photographer, Mark Johnson. Enjoy his answers.

Cyclismas: Your cycling roots go back to the 1980s. I guess you must have known then of guys like Wayne Stetina and John Vande Velde. Two, three decades on and you’re telling the story of the team that Peter Stetina and Christian Vande Velde ride with. Is that cool, or does it just make you feel old?

Mark Johnson: It’s cool, and when I’m around the younger guys like Dan Martin and Peter Stetina their enthusiasm makes me feel younger than my 47 years!

Cyclismas: Jonathan Vaughters opened his introduction to Argyle Armada with a quote from Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities. It’s a much abused and rather clichéd quote at this stage – ‘It was the best of times, it was the worst of times’ – but, for once, used aptly. Let’s take both sides of the picture, the worst first. Garmin started the 2011 season with the dismissal of Matt White, ended it with the folding of the women’s team. There were all sorts of other issues during the year, from the way the team dropped riders so they couldn’t take points to rival teams, through the tension with Thor Hushovd and the team’s role in the race radios brouhaha. Fair to say it was the year the team grew up, lost a lot of its innocence?

Mark Johnson: I also cringed when I saw that quote, but it’s what JV chose and in the end it fits the year and his intro.

I believe that what the team lost, and Vaughters told me this more than once, was the ability to position themselves and ride as just the ‘100% clean team.’ For the sake of their fans and their sponsors, they had to move beyond a marketing slogan (one they backed up with substance, nonetheless) and start delivering wins.

So yes, in the sense that they had to move beyond the peach-fuzzy gloss of youthful enthusiasm and promises and start delivering substantial wins, they did lose some innocence. Beyond that, they still maintain a degree of the fifteen-year-old’s goofiness that other teams don’t have.

Cyclismas: The good times. If you’re only going to win one Classic in a year, you might as well let it be the Queen of the Classics, Paris-Roubaix. You were in the little vélodrome in Roubaix when Johan Vansummeren broke away at the Carrefour de l’Arbe, fifteen kilometres out. You watched on the big screen as Leopard’s Fabian Cancellara began his chase, Thor Hushovd unable to hold his wheel. You knew what Vansummeren was capable of, you knew what Cancellara was capable of. For you, personally, as someone who has been a freelance writer and photographer with the team since 2007, what was watching those final few miles like?

Mark Johnson: Even though it seems like I saw more of this team in 2011 than my own wife and family I tried to maintain journalistic objectivity and distance with the team. The moment Vansummeren rode into that vélodrome was one of the moments those efforts collapsed.

Johan Vansummeren enters the vélodrome in Roubaix as he solos to victory in the Queen of the Classics. (Photo courtesy of Mark Johnson)

That moment reminded me of two other sporting moments that will forever resonate with me: the day the US Olympic team beat the USSR in ice hockey in 1980 and the afternoon Greg LeMond won the Tour in that dramatic TT win over Laurent Fignon in 1989. All three were simply electrifying, and that’s saying something for a person who is not really that big on sitting around on a Saturday afternoon watching sports on TV.

The Roubaix win was emotional especially because Vansummeren is as humble as he is tall. He is such a deserving winner, and the fact that the Belgian water carrier from Lommel did it at a race that, while technically in France, feels as much a Belgian classic as Flanders the Sunday previous, made it all that more poignant to see him win.

The fact that Thor Hushovd sacrificed his own Roubaix victory desires to make it happen made it even more touching, and that really came through as I observed Thor’s face display a chiaroscuro mix of melancholy and joy in the team bus after the race.

Also, the day was such a joyous contrast to the clinical, all-for-Lance disciplinary methodology Armstrong employed to win races. That Roubaix day put an alternative spin on the way American teams have traditionally won at the highest level of cycling.

Cyclismas: The team had two pretty successful Grand Tours, in France and Spain, but the mood between the two – certainly as you paint it in Argyle Armada – was markedly different. The Tour was like one long, extended party, the Vuelta like a rite of passage. Did that surprise you, or are you used to that in the Vuelta?

Mark Johnson: It didn’t surprise me, but it was certainly a striking contrast and I’m glad it came through in the narrative. Those boys were really suffering at the Vuelta.

While the flush of victory carried them through the pain – and disguised it to a degree – at the Tour, the sheer, gruelling brutality of a three week stage race was so much closer to the surface at the Vuelta. At the breakfast table, dutifully spooning oatmeal past their teeth, they truly had the faces of slaves of the road.

Cyclismas: Park the big moments a moment, Paris-Roubaix, leader’s jerseys in all three Grand Tours, stage wins and the like. Let’s look at the little moments instead, those moments of magic that really enhance our love of cycling. Biggest little moment of the year for you?

Mark Johnson: One of the biggest was also one of the quietest: watching Christophe Le Mével push that boy over a hill in the Belgian Ardennes during their LBL recon ride was profoundly touching to me. I mean, Christophe didn’t need to do that, but he took the time and there is no telling how that moment might affect the trajectory of that kid’s life. As Paul Kimmage told me, they just seemed like decent people.

Also, seeing how much not winning Colorado and the Canadian races affected Ryder Hesjedal and Christian Vande Velde endeared me a bit more to the sport. The root of their disappointment was of course personal – anyone at that level of racing must be fuelled by a selfish desire to win. But I was really struck by their expressions of how their disappointment stems from their failure to deliver a legacy to the young kids watching them. In other words, the source of their disappointment at not winning was also extrinsic – focused on others – as much as it was rooted in ego. I guess I didn’t expect to find what were basically selfless impulses fuelling their sense of failure.

Another moment that comes to mind was sitting down with Thor in Pinerolo, Italy, after stage seventeen of the Tour. Hushovd is generally a pretty reserved guy; he’s nice, but he just doesn’t say much and keeps to himself. On this day, he really opened up about his frustration with the riders’ lack of consequence and leverage in the organization of their sport. They may be the stars on the road and in the eyes of the public; but when it comes to affecting the design of their profession, they aren’t even water carriers, and that dichotomy seemed to really bother Thor.

It was all the more moving because at that moment, Hushovd was poised at the acme of his profession – three more Tour stage wins, seven more yellow jerseys, the rainbow stripes – yet, when the subject turned to the business of cycling, his mood was one of dejection and frustration, not celebration.

It’s funny because, earlier that day, someone introduced me to Thor (not realizing that I had been haunting him since January) and Hushovd responded, ‘Oh, I know Mark, he’s like family.’ I guess I had developed familiarity with some of the riders to a degree I didn’t realize. I certainly did not try to fraternize with them throughout the year; I just watched and observed and gave them their space when I sensed it was time for me to do so. I can only hope my book treated them fairly and honestly.

Thor Hushovd at the Garmin-Cervélo team presentation, Girona, January 2011. (Photo courtesy Mark Johnson)

Cyclismas: Peloton politics pepper the story you tell in Argyle Armada, the big issues such as race radios, the UCI’s role in our sport, financial concerns, the lack of a riders’ union etc. Having spoken to Garmin’s riders, and others within the peloton, how would you describe the cohesiveness of the riders themselves when it comes to having a voice on these key issues?

Mark Johnson: The riders generally express the same concerns you summarize in your question, and they also all cited the same general reasons why they are not organized (language, judicial jurisdictions, socio-economic variations).

But until someone like a Marvin Miller arrives with the focus, energy, experience, and talent to organize them and skilfully negotiate with the existing power holders, I don’t see anything changing. A rider can’t do it. It’s too much to be both a professional labour organizer and a professional athlete at the same time.

Cyclismas: Everybody admits that cycling is tied to tradition. But it’s never been a sport stuck with just one way of doing things, it’s constantly evolving. Ten years ago the Tours of Oman and Qatar were hardly even dreamt of. Twenty years ago French was still the lingua franca of the peloton. Thirty years ago women were only slowly becoming a part of team personnel. Forty years ago the UCI had virtually no power. Fifty years ago anti-doping rules were in their infancy. Cycling never stands still. The changing attitude to doping aside, what’s the most important change you’ve witnessed since first coming to the sport?

Mark Johnson: The emergence of English as the lingua franca of the peloton. Notwithstanding the fact that the photographers’ briefing meetings at the ASO events are still in French (and why not, it’s a French organizer, and most of the photogs speak French anyhow), the fact that English is now the language of the business and sport of cycling portends a larger shift in power that I suspect may happen once higher-functioning business people realize how much money is being left on the table by pro cycling’s current status as, in Christian Vande Velde’s words, the world’s biggest amateur sport.

Also, the booming popularity of the sport among participants in the US and in Europe. It’s stunning to see how many everyday people have become enthralled with riding the bike, and I think that on-the-ground passion will help the professional side of the sport, once it gains more professional management.

Am I concerned pro cycling will turn into a soulless, two wheeled F1? Not really; universally, among all the insiders I spoke to throughout the year about the future of the sport, maintaining a balance between the sport’s primitive appeal while also giving it more management maturity was constantly mentioned as essential to the sport’s longevity. I hope that came through in the book!

Finally, while it’s fashionable to bash the UCI (and they often deserve the beatings), it seems to me they have done more than many other pro sport governing bodies to try and crack down on doping. Yes, their application of rulings and enforcement consistency is lacking, if not corrupt, at times; their infantilization of the riders is undignified; and basic human dignity seems secondary to the UCI’s impulse to hang suspects out to dry in the court of public opinion. But compared to the big American sports, where doping infractions bring a slap on the wrist, the UCI has forced pro cycling to confront its doping problems. Does the clean end justify what can seem to be some scandalous UCI means? I don’t know. Regardless, along with what seems to be a changing acceptance of doping among many of the younger riders, I think the diminished acceptance of doping is an important change – if it lasts.

Cyclismas: Cycling, a lot of people tell us, is too complicated. It needs to be simplified so that fans can understand it. Because, apparently, we don’t actually understand it at the moment. You followed Garmin for most of a season, from the Classics through Cali, on to the Tour, through the Quiznos Challenge and the Vuelta, and then on to the two Canadian races. Each race was different, each race was contested by different groups of riders, sometimes races were on in one place while another was ongoing somewhere else. Given that you’ve had to sit down and explain those races to fans, to unify a season, what would you change?

Mark Johnson: I’d more clearly delineate the top level races. The UCI is kind of stumbling in that direction with the ProTour, but then you’ve got something called the WorldTour – and what the heck is the difference? And the fact that a brand new race with no fans on the roadside, a blanket of filth in the air, and a bunch of listless, bemused riders like Beijing can get WorldTour status while still in the newborn ward discredits the prestige of the entire series.

Give the new fan something they can get a grip on if they want to know what to tune into for the most important races in the most spectacular settings with the best riders racing. And then, at the end of the year, let those key races crown a season champion.

I tend to agree with Serge Arsenault [organiser of the two WorldTour races in Canada] in the book; the template is already there.

Cyclismas: Photography. Like riding a bike, it’s something anyone can do, so a lot of people think it’s not all that hard. Point, press, hey presto, a classic image. The reality is a little bit different: there’s a wee bit more to it than just pointing your iPhone at the peloton as they whiz past and cleaning up in the image in PhotoShop or filtering it through Instagram. Care to share some insight as to the type of kit you cart round with you, the pros and cons of digital over film, and what life’s really like behind the lens?

Mark Johnson: I have a blog post on exactly what kind of camera stuff I lugged around with me while shooting this book, rather than rehash that here, I will leave you to look at that.

The conversion to digital from film is a blessing and a curse. For new photographers, it’s a blessing because you can ramp up your skills without the cost of film and developing. Getting instant feedback on the back of your camera on what works and what doesn’t makes this a fabulous time to start taking photos.

For professionals, the curse is that you shoot a lot more images than with film, which means you have to spend more time editing those photos down to a few selects. The product delivery time-frames are a lot shorter now, too. There is no more post-event down time while you or a lab develop film.

Of course, the pressure to be in the right place at the right time is always there, too. With experience, you gain confidence in your equipment and your control over it and light, so you don’t worry so much about getting the key finishing shot. Even when your equipment fails (and it does, especially with the beatings it takes shooting cycling photography), you also learn to stay calm and get the shot with crippled machinery. With this book, there was way more pressure in deciding what to leave out than stress over what I had missed.

Cyclismas: Jonathan Vaughters is one of the leading voices in the battle to make the race organisers let the teams have a (greater) share of their profits, specifically linking this argument to the sharing of TV revenues. Let’s take that point to its logical conclusion: photographers, like you, should share a slice of your income with the teams, riders, and races you photograph. Ditto a percentage of your income from writing about them. How much would you be willing to fork over to feed the machine, to keep the wheels going round, to save everyone from having to stick with a system that – we’re told – is broken?

Mark Johnson: When a steel and auto economist and labour organizer named Marvin Miller organized professional baseball players in the mid-1960s, one of the first things he did was renegotiate the raw deal the players had negotiated with a major manufacturer of baseball cards. The players were essentially giving their images away for life and getting very little in return.

While pro cyclists may not be able to negotiate with the ASO yet over TV revenue sharing, it seems to me they would do well to federate themselves and gain control over the use of their images to market products and sell dreams. For example, a cohesive riders league could then go to a manufacturer who wants a rider to endorse their product and say, OK, you can do that, but these are the economic terms, and part of your advertising and production spend is going to go back to the riders’ league and be shared by all the riders. (This sort of careful image management is standard in most sports and entertainment businesses, but not in cycling.)

While it would make life more complicated for photographers like me, I think in the end such a change might benefit everyone by increasing rates all the way around. When negotiating licensing terms with a manufacturer, all the parties would know that part of the photographer’s licensing fee would have to go to the league, and rates would adjust accordingly. Today, anyone can grab a good photo of a rider and flip it over to a manufacturer for peanuts or for free, and that harms working photographers who shoulder significant capital and overhead expenses.

As far as how much I’d be willing to fork over; it would make sense to look at the models other sports use and start there. That’s one of the nice things about cycling being in such a primitive state as a business – as it matures it can learn from the mistakes and successes of other pro sports like F1, soccer, baseball, tennis and golf and hopefully follow the good and avoid the bad.

Cyclismas: Let’s go back to the book. Argyle Armada is a mix of words and images. It’s not quite the conventional coffee table cycling photo album some might take it to be: the words and the pictures work together synergistically. I tried to compare it with other cycling books in the review, but did you have a particular model in mind?

Mark Johnson: What I had in mind was a series of New Yorker–like day-in-the-life chapters that were illustrated by photographs. Because there is so much political, social, and economic import to what Jonathan Vaughters is trying to do with this team, I had no interest in doing a photo-only book with captions.

I adore the crafts of both writing and photography – they both involve the thoughtful and selective application of light and shadow, with degrees of gradiated penumbra between the two. My model was a book that would use both mediums (writing and photography) to illustrate a year with the team with a degree of richness that would be difficult to do with either just narrative or photos alone.

In the end, I am pleased with how well the photos match the narrative. My editor at VeloPress, Ted Constantino, was a big help in deciding which photos go where. As a photographer you become emotionally attached to certain photos for aesthetic or personal reasons. Having an editor like Ted who could say, ‘yes, it’s a pretty photo, and it’s technically spot on, but it doesn’t propel your story, so we should leave it out,’ was exceptionally helpful for me.

Cyclismas: Let’s get back to the team, and to the riders. Two hats for you, and I want you to give me two riders: wearing your professional’s hat, who’s best in front of the camera, or gives the best copy; and, wearing your fan’s hat, who are you rooting for the most?

Mark Johnson: One of the luxuries I had in spending a year with the team is that I did not have to rely on the post-race sound bites. Immediately after an event, the riders are exhausted and can go into media management mode – just say enough to celebrate your team and plug the sponsors for the bristling array of microphones in your face, then get back to a shower and a plate of warm food. It’s completely understandable.

However, since I had a year to file my story, I could go back to the riders and interview them a week or a month after an event and collect their more measured thoughts after they had time to process and ponder the race-day drama. And that means, with almost all the riders, they simply told me more than I could have ever expected. For example, Johan Vansummeren a week after Roubaix telling me about his crushing stress riding in with a flat tire.

Christian Vande Velde at the races would have his game face on and not say much to me at all. But when I followed up with him a few weeks after the Tour of Colorado, while he was riding around on a tractor in his back yard, he was genial and loquacious and seemed willing to chat all day about his career, the race in Colorado, and the state of the pro cycling profession.

I think the most eloquent observers on the state of pro cycling were Jonathan Vaughters and Tyler Farrar. The best man for sound bites is Dan Martin – that one has spunk, and seems to have been trained in the Chris Horner school of speak your mind honestly. A base man will forever avoid you. Of course, a half hour with David Millar will set your tape recorder on fire. He’s a forceful, eloquent, thought-provoking man.

As for who I was rooting for with the fan hat on, Sep Vanmarcke, Ramunas Navardauskas and Murilo Fischer come to mind. All three are just delightful, warm-hearted human beings, and young Sep and Ramunas represent pro cycling’s bright future. I had many heart-warming conversations with Murilo in Spanish, since my Portuguese is so miserable. I also think back fondly to a day that he and Dan Martin took me on a bike ride down some of the most scenic, out of the way roads that I would have never, ever found on my own in Girona. The kindness and warmth of these riders also stands in such contrast to their fearsome capacity on the bike.

Dave Zabriskie remains a cipher to this day. Even after speaking to him at length on multiple occasions and watching him for a year, he remains an enigma to me. A charming question mark with a sly and lively sense of humour, but a tough one to crack nonetheless!

Cyclismas: The big thing this year is going to be the team time trial at the World’s, the riders being asked to forget their national colours and don their trade team jerseys again for a day. That’s a race Garmin-Barracuda are targeting. I’ve grown up listening to cycling journalists slagging off TTTs at every opportunity, but this one is shaping up to be a helluva lot of fun.

Mark Johnson: Yes – that is going to be a great race. And the TTT is the only kind of TT that doesn’t look like paint drying when watching it on TV.

Cyclismas: Are there plans for an Argyle Armada II: On Stranger Tides?

Mark Johnson: Not yet on this team – I’ll give them a couple more years before I’d consider circling around again for another book. But, oh man, along with doing a lot of book promotion talks and slide shows, I have magazine articles and race coverage assignments stacked in my queue like planes on the LAX runway. But I’m grateful for the work and happy to have cheques landing in the mailbox!

I had a publisher approach me about doing an Argyle Armada type book on a pro triathlete, and that might be interesting, if there are politics and culture involved. A photographer named Liz Kreutz did a photo book on a year with Lance Armstrong. Something similar on a compelling triathlete but with a substantial written narrative might interest me. And since GreenEdge is linked to something larger, a nation of restless immigrants, that’s a team that might stand up to a book-length treatment like Argyle Armada.

I like to write about people. My dream assignment would be to write a piece on Jonathan Vaughters for The New Yorker. So if any of your readers have contacts at that citadel of high culture and fine writing, please feel free to get in touch with me!

* * * * *

Mark Johnson is the author of Argyle Armada – Behind the Scenes of Pro Cycling Life, published by VeloPress (2012, 207 pages). (Read the review here.)

You can find him online at ArgyleArmadaBook.com and on Twitter, @ArgyleArmada.

Our thanks to Mark Johnson for taking part in this interview.

3 Comments

[…] Check out the interview. […]

[…] Cyclismas – Interview Mark Johnson – Mark is the guy behind the book, The Argyle Armada, and give a very insightful look into what it is like following and chasing a pro team for a year … […]

[…] other day an interviewer asked me to put on my fan cap and tell his readers who my favorite team riders were. I mentioned Ramunas Navardauskas–the […]