In the first part of a series of articles looking at the 1924 cycling year, we introduce some of the key characters and key issues that drove our sport nine decades ago.

It was all such a long time ago. In 1924 the cycling world was still young, though thought itself all grown up. Six Day track racing had been around for just shy of 50 years, place-to-place races had been going five or six years longer than that. Pneumatic tyres, chain-driven bikes, the free-wheel, these were all already old hat back then. Oh how the cyclists of 1924 must have looked at themselves, impressed at all they’d achieved, how far their sport had come. Did any of them then dare to imagine the state their sport would be a century on, that many of the same races they rode then would still be being raced well into the next millennium?

What, can you imagine, would the cyclists of 1924 think of what we’ve done with their sport? What would they think of a world in which teams bitch and moan about the need for race organisers to pay them more just to turn up and take the start? Of a world in which doping is seen as being an essential aspect of the sport? Of a world in which women are fighting for a fair share of the sport’s limelight?

For the riders of the 1924 cycling season, if you could travel back in time and tell them that today, in 2012, these are the issues we talk about when we talk about cycling, those riders from nigh on nine decades ago would laugh at you. Loudly. Rocking back on their feet and almost falling over because of their laughter. And then they’d slap you on the back and pity you for your lack of imagination. For, in, 1924 cycling was confronting the very same issues. The sport then may seem distant to us now. The bikes were a little bit different, for sure. The roads were nowhere near to what they are like today, of course. But the riders were the same, and the issues that they faced were – are – timeless.

Trying to turn the clock back and look at the 1924 cycling season isn’t as difficult as you might imagine. Okay, yes, this isn’t going to be a comprehensive look, we’re not going to consider every race and every rider. Rather it’s a trawl through what has been written about the 1924 cycling season already, stories told here, stories told there, stories pulled together from different sources to see how they fit together. To see if cycling’s history has any lessons to teach us, or is just a source of some entertaining stories.

One of the biggest difficulties in looking at a cycling season so long ago is one of language. Cycling had its own language. We talk of things like the maglia rosa, of races like Ghent-Wevelgem or the Flèche Wallonne, of heroes like Coppi, Merckx, Hinault. In 1924, none of them were a part of cycling’s lexicon. That – for me – has always been the hardest thing about looking at old cycling stories: the names mean nothing. For the purpose of economy, let’s try this quick introduction to some of the names – the riders, the teams – that cycling fans in 1924 would have been cheering for:

| Major Races And Their Winners, 1919-1923 | |||||

|

1923 |

1922 |

1921 |

1920 |

1919 |

|

| Milan-Sanremo (1907) |

Costante Girardengo Maino Italy |

Giovanni Brunero Legnano Italy |

Costante Girardengo Stucchi Italy |

Gaetano Belloni Bianchi Italy |

Angelo Gremo Stucchi Italy |

| Ronde van Vlaanderen (1913) |

Henri Suter Gurtner Switzerland |

Léon Devos Independent? Belgium |

René Vermandel Independent? Belgium |

Jules van Hevel Independent? Belgium |

Henri van Lerberghe Legnano Belgium |

| Paris-Roubaix (1896) |

Henri Suter Gurtner Switzerland |

Albert Dejonghe Independent? Belgium |

Henri Pélissier Automoto France |

Paul Deman Independent? Belgium |

Octave Lapize Independent? France |

| Paris-Tours (1896) |

Paul Deman Lapize Belgium |

Henri Pélissier JB Louvet France |

Francis Pélissier Automoto France |

Eugène Christophe Independent? France |

Hector Tiberghien Independent? France |

| Giro d’Italia (1909) |

Costante Girardengo Maino Italy |

Giovanni Brunero Legnano Italy |

Giovanni Brunero Legnano Italy |

Gaetano Belloni Bianchi Italy |

Costante Girardengo Stucchi Italy |

| Bordeaux-Paris (1891) |

Emile Masson Alcyon Belgium |

Francis Pélissier JB Louvet France |

Eugène Christophe Independent? France |

Eugène Christophe Independent? France |

Henri Pélissier La Sportive France |

| Tour de France (1903) |

Henri Pélissier Automoto France |

Firmin Lambot Peugeot Belgium |

Léon Scieur La Française Belgium |

Philippe Thys La Sportive Belgium |

Firmin Lambot La Sportive Belgium |

| Liège-Bastogne-Liège (1892) |

René Vermandel Alcyon Belgium |

Louis Mottiat Alcyon Belgium |

Louis Mottiat Alcyon Belgium |

Léon Scieur La Sportive Belgium |

Léon Devos Independent? Belgium |

| Giro di Lombardia (1905) |

Giovanni Brunero Legnano Italy |

Costante Girardengo Bianchi Italy |

Costante Girardengo Stucchi Italy |

Henri Pélissier La Sportive France |

Costante Girardengo Stucchi Italy |

| Source: Memoire du Cyclisme | |||||

Teams are going to be important to this story, so some brief comments about them. Back then, teams were quite different. For a start, they were, by and large, all sponsored by people directly involved in the sport, usually a bike manufacturer, with a tyre or component company as co-sponsor. (I’ve given only the main sponsor above.) For the riders, teams required their presence at certain races – where a directeur sportif and team support would be on hand – but at other races they were on their own.

Cycling was quite regional, almost nationalistic: Italian riders, typically, rode in Italy; French riders in France; Belgian riders in Belgium. There was some mobility, especially among the better riders – and where races were close to national borders – but cycling was still a rather local affair. This wasn’t xenophobia, but a matter of economics: what was the point in a Belgian rider travelling all the way to Italy for a race if his winnings would be wiped out by travel expenses? Sponsors were also tied to their market. If they didn’t sell in a particular market, then there was little or no point in them underwriting the expense of sending a team to race there. Particularly when it involved crossing borders, riders might get sponsorship from a local team for such events. So while, say, the Pélissiers typically rode for French teams, in Italy they sometimes raced in Bianchi’s colours.

While the best riders got contracts to ride for sponsored teams, the rest could still enter the big races, riding as independents, responsible for themselves and riding just for the prize money, or the glory. In the Tour de France, these were the isolés, later the touristes-routiers. In the Giro d’Italia they were the isolati. They were responsible for finding their own lodging, sorting out their own food and looking after their own bikes. In the stage races, with the organised teams, the attending journalists, a smattering of fans and the race organisers all bagging the best hotels, sometimes even the simple task of finding somewhere to sleep for the night could be a major undertaking for an unsponsored rider.

Who were the teams of the moment in 1924? In France, that would have been Alcyon, Automoto, La Française and Peugeot. Alcyon had guys like Nicolas Frantz (25), Federico Gay (28), Louis Mottiat (35), and René Vermandel (31). Automoto had the likes of Honoré Barthélémy (33), Ottavio Bottecchia (30), Francis Pélissier (30) and Henri Pélissier (35). La Française had Arsène Alancourt (32), Albert Dejonghe (30) and Paul Deman (35). Peugeot could field the likes of Henri Suter (25), Philippe Thys (35) and Hector Tiberghien (34). There were other teams – such as Armor, Ganna, Griffon, JB Louvet, Labor – who could count on one or two riders each, but for the most part, the key French teams were those four.

In Italy the teams of the moment were Maino and Legnano. Maino had riders like Costante Girardengo (31) and Angelo Gremo (37). Legnano had Giovanni Brunero and Gaetano Belloni (32). Neither Atala nor Bianchia were fielding strong squads in 1924 but they were historic names of the sport.

The ages of riders is worth considering: riders were riding through their early-to-mid thirties. There’s a couple of factors at play here: the first is the obvious one – a generation had been lost to the Great War. But there’s also a sporting factor. If you think about what cycling was back then, this shouldn’t seem odd. It was an endurance sport. Epic. How epic it should be was one of the key issues of the day. Particularly in France. Why? Because the Belgians were beating the French senseless.

The Belgians – flahutes to a man – rode like they were powered by Duracell batteries. They just kept going and going and going. Between Odile Defreaye, Philippe Thys, Firmin Lambot, and Léon Scieur Belgium ruled the Tour between 1912 and 1922. It took a rider who had a rocky relationship with Henri Desgrange to tame Flanders’ lions and reclaim the Tour for France. That man was Henri Pélissier, winner of the 1923 edition of the Tour.

The difference between French and Belgian riders is evidenced in the ways in which Pélissier was praised. “The swift, noble whippets,” l’Auto proclaimed following Pélissier’s Tour win, had been provided “victory over the hardy, resistant grafters.” Good, clean stuff, whippets and grafters, the hero ennobled and the losers praised. A lot more diplomatic than the headline printed two years earlier, following Pélissier’s 1921 Paris-Roubaix victory, when l’Auto had run with: “The thoroughbred triumphs: Victory of the best.” It was to that horse-breeding theme that André Reuze turned when he made his assessment of the outcome of the 1923 Tour: “The thoroughbreds have got the better of the workhorses.” That was the way many saw Belgian riders: a bunch of dumb cart-horses, no style, no class, just an ability to go on and on and on. And a sport for cart-horses is where many thought cycling was going: super-long distances that were more and more about finding out who could be the last man standing.

* * * * *

Francis and Henri Pélissier, Federico Gay, Honoré Barthélémy, Ottavio Bottecchia, Costante Girardengo, Giovanni Brunero, Gaetano Belloni – those names are going to crop up a lot as the story of the 1924 season is told. But, before moving into the 1924 season itself, there is one other rider who needs an introduction: Alfonsina Strada.

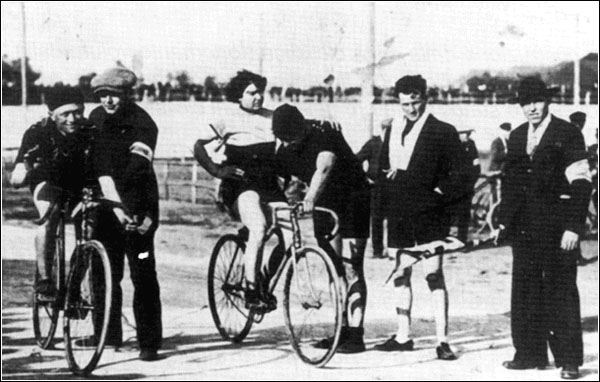

Alfonsina Strada in 1923. The rider on the left is Giovanni Gerbi (nicknamed “The Red Devil”), the greatest Italian rider never to have won the Giro. (Source: BikeRaceInfo.com)

Born Alfonsa Morini in Castlefranco, Emilia, Strada was one of four daughters and six sons born to her peasant parents, the second eldest child. When Strada was four her parents moved to Castenaso, near Bologna. Aged ten she discovered cycling, after her father came home one day with a bike he’d bought for himself, trading a local doctor some chickens for the machine. Strada soon learned to ride it.

When Strada started entering – and winning – bike races, locals began to call her the Devil in a Dress (Giovanni Gerbi, against whom she raced at least once, was known as the Red Devil). In 1907 she defeated Giuseppina Carignano, becoming the Italian champion. Though her parents tried to dissuade her from her cycling aspirations, a rider from her native Emilia by the name of Carlo Messori offered her encouragement and, in 1909, Strada was one of a group of riders who went to Russia to ride the GP St Petersburg, where Tsar Nicholas II presented her with a medal.

Two years later Strada established a new endurance record for women, riding 37.192 kilometres in an hour, beating Louise Roger’s 1905 ride. The men’s hour record was about to enter the era of the great Marcel Berthet/Oscar Egg rivalry, with five successful attempts on the record over the next three years, stuffing 2,727 metres onto Berthet’s 1907 record (41.52 kilometres). But, popular and all as the men’s hour record was, the UCI had yet to get around to recognising a women’s hour record. It would be 1955 before the women got their own page in the UCI’s record books, when Tamara Novikova rode 38.473 kilometres. At that point the men’s record stood at 45.848 kilometres, Fausto Coppi’s ride from 1942. A seven or eight kilometre difference between the men’s record and the women’s stayed more or less constant for the next few decades, each new women’s record being about that far behind the male version. Looked at in that light, Strada’s 1911 ride was more than respectable.

In 1915 she married Luigi Strada. While her family had tried to discourage Strada’s passion for cycling her husband actively encouraged her: as a wedding gift he presented her with a new racing bike. Strada was by now somewhat famous, certainly within the sport in Italy, and even abroad: her popularity saw her racing on the track in France, in the heartland of Henri Desgrange’s fiefdom, Paris’s vélodromes, the Buffalo, the Vél d’Hiv, and the Parc des Princes. In 1917 – by which time she was living in Milan – Strada rode her first Giro di Lombardia, at the invitation of La Gazzetta dello Sport.

Unlike the British, the Italians had no formal rules forbidding women from racing in their events. They did have social conventions and Strada was breaking a taboo by taking the line in such an important race. But, with many of the best male riders of the day away fighting the war, the publicity – and the polemica – generated by Strada’s appearance was welcomed by the race director, Armando Cougnet and his newspaper, La Gazzetta.

Thus it was that, on November 4 1917, a little after eight of a crisp autumnal morning, Strada took the line in Milan alongside riders such as Gaetano Belloni (Bianchi), Costante Girardengo (Bianchi), Henri Pélissier and Philippe Thys (Peugeot). Belloni was there by virtue of having been excused war duty because he was digitally challenged, having lost a thumb in an industrial accident when he was a textile worker. Girardengo, who was now 24, was excused conscription because he was, officially, an industrial worker. Thys was running some sort of haulage business up near Brussels. As for Pélissier, a few sources claim he was on leave from the army for this race.

From the gun Pélissier set a cracking pace and soon a group of six riders opened up a gap on the rest: Girardengo, Charles Jusseret, Luigi-Natale Lucotti (Bianchi), Pélissier, Thys and Leopoldo Torricelli (Maino). At Brinzio, heading out toward Varese, Giuseppe Azzini, Belloni and Angelo Gremo (Bianchi) were within sight of the break, which they soon closed in on, leaving a group of nine off the front of the race.

At Binago on the way back from Varese, Girardengo and Belloni lost contact with the break. Coming into Como it was a group of five – Jusseret, Lucotti, Pélissier, Thys and Torricelli – with a two minute lead over Azzini and five minutes over Belloni and Girardengo, who had by now been joined by Alfredo Sivocci (Dei) (Gremo by now must have been stuck in no man’s land between the groups). At Cicognolo the two Belgians – Jussaret and Thys – tried to work the other three over and forge an escape, but Péllissier wasn’t letting them away with that sort of move. The group of five crested the climb with a lead of three minutes and stayed together to the finish back in Milan.

Entering the track, Jussaret led the group of five. Torricelli tried to go clear on the last bend but the two Belgians nullified his move. Coming onto the finishing straight, Lucotti lost the wheel in front of him and it was looking like a four-up sprint, with Jussaret leading out Thys, a comfortable victory for Belgium. But Pélissier was watching and went with Thys when he made his move a hundred metres out. In the last ten metres the Belgian and the Frenchman were side by side, banging and barging one and other in the rush for the line. It took the blazers a bit of time to decide who got the glory, the Belgian or the Frenchman, in the end giving the win to Thys, much to Pélissier’s disgust.

More than three minutes behind them Belloni arrived in a group of four riders, which included Gremo and Sivocchi. Girardengo was 15 minutes down on the day, rolling in alone to take tenth. That was the race at the front: as exciting a Lombardia as you’d find today. Of the 54 riders who took the start – 74 had entered but 20 were no shows – only 31 completed the 204 kilometre course. Strada was not among the abandons: an hour and 34 minutes behind Thys, the light gone and the time getting on for five in the evening, Strada raced into the vélodrome alongside two other riders, Pietro Sigbaldi and Gino Auge. Officially, Strada was 29th and last on the day. (Two riders who finished ahead of her – A Necchi and Davide Chiesi, who were 37 and 47 minutes behind Thys – were disqualified for failing to sign in properly at the finish.)

| Giro di Lombardia 1917 (204 kms – 29.28 kph) |

||||||||

|

Pos |

Name |

Country |

Time |

|

Pos |

Name |

Country |

Time |

| 1 | Philippe Thys Peugeot |

Belgium | 6h58’02” | 16 | Lauro Birdin | Italy | à 47’00” | |

| 2 | Henri Pélissier | France | à 0″ | 17 | Michele Robotti | Italy | à 47’00” | |

| 3 | Leopoldo Torricelli Maino |

Italy | à 0″ | 18 | Alessandro Tonani | Italy | à 47’00” | |

| 4 | Luigi Natale Lucotti Bianchi |

Italy | à 0″ | 19 | Giuseppe Bottazzi | Italy | à 47’00” | |

| 5 | Charles Jusseret | Belgium | à 0″ | 20 | Luigi Cuppi | Italy | à 47’00” | |

| 6 | Gaetano Belloni Bianchi |

Italy | à 3’25” | 21 | Paolo Restelli | Italy | à 47’00” | |

| 7 | Angelo Gremo Bianchi |

Italy | à 3’25” | 22 | Attilio Caldara | Italy | à 48’00” | |

| 8 | Romeo Poid | Italy | à 3’25” | 23 | Virgilio Zinnaro | Italy | à 48’00” | |

| 9 | Alfredo Sivocci Dei |

Italy | à 3’25” | 24 | Angelo Tommasini | Italy | à 48’00” | |

| 10 | Costante Girardengo Bianchi |

Italy | à 15’00” | 25 | Gino Masseroni | Italy | à 1h32’00” | |

| 11 | Ruggero Ferrario | Italy | à 19’00” | 26 | Luigi Bassi | Italy | à 1h33’00” | |

| 12 | Arturo Ferrario | Italy | à 19’00” | 27 | Pietro Sigbaldi | Italy | à 1h34’00” | |

| 13 | Pietro Bestetti | Italy | à 19’00” | 28 | Gino Auge | Italy | à 1h34’00” | |

| 14 | Camillo Bertarelli | Italy | à 31’00” | 29 | Alfonsina Strada | Italy | à 1h34’00” | |

| 15 | Pietro Aymo | Italy | à 31’00” | |||||

| Source: Museo Ciclismo | ||||||||

The following year Strada again rode Il Lombardia, run just a week after the war officially ended. The 1918 Lombardia was shorter – only 190 kilometres – and a much more sedate affair than the previous year’s edition. This time it was run off under grey skies but again without rain. At 7.45 in the morning, 36 of the 40 registered entrants took the line. Strada was again racing alongside some well-known riders, including Belloni (Bianchi) and Sivocci (Dei) as well as Legnano’s Carlo Galetti (the winner of the 1910, 1911 and (unofficially) 1912 Giri d’Italia). Also taking the line was Eberardo Pavesi, who had been part of the Atala squad that won the 1912 corsa rosa and would soon go on to become a famous direttore sportivo.

The peloton rode lazily until they hit Brinzoni when a group of seven, which included Belloni and Galetti, opened a small lead. Coming back over Brinzoni from Varese fourteen riders were at the front. Belloni tried to get away on his own at Cappelletta but was quickly brought back. At the start of Cicognola the peloton had grown to twenty strong. By the bottom of the descent that was down to a dozen riders. With 20 kilometres to go these twelve held a lead of four minutes over the chase behind. They stayed clear until the finish.

In the last kilometre Belloni went long, with Sivocci hot on his heels. A dog slipped onto the course. Lucotti went down. Belloni and Sivocci were by now contesting the sprint, ignorant of what was happening behind them. Just 20 metres from the line Belloni went clear and took the victory salute, with Sivocci close behind. Galetti rounded out the podium. Twenty-three minutes down on Belloni’s time, a group of seven brought up the rear of the race. This time the Regina della Pedivella, the Queen of the Cranks, finished second last. But at least she had, again, finished.

| Giro di Lombardia 1918 (190 kms – 26.636 kph) |

||||||||

|

Pos |

Name |

Country |

Time |

|

Pos |

Name |

Country |

Time |

| 1 | Gaetano Belloni Bianchi |

Italy | 7h8’0″ | 12 | Mario Santagostino | Italy | a 4’0″ | |

| 2 | Alfredo Sivocci Dei |

Italy | a 0″ | 13 | Giovanni Marchese | Italy | a 6’0″ | |

| 3 | Carlo Galetti Legnano |

Italy | a 0″ | 14 | Pietro Bestetti | Italy | a 7’0″ | |

| 4 | Alexis Michiels | Belgium | a 0″ | 15 | Eberardo Pavesi | Italy | a 18’0″ | |

| 5 | Leopoldo Torricelli Dei |

Italy | a 0″ | 16 | Pietro Aymo | Italy | a 23’0″ | |

| 6 | Giuseppe Azzini | Italy | a 0″ | 17 | Francesco Marchese | Italy | a 23’0″ | |

| 7 | Clemente Canepari Stucchi |

Italy | a 0″ | 18 | Mario Mosca | Italy | a 23’0″ | |

| 8 | Lauro Birdin Bianchi |

Italy | a 0″ | 19 | Vincenzo Accomolli | Italy | a 23’0″ | |

| 9 | Romeo Poid | Italy | a 0″ | 20 | Dario Balboni | Italy | a 23’0″ | |

| 10 | Arturo Ferrario | Italy | a 0″ | 21 | Alfonsina Strada | Italy | a 23’0″ | |

| 11 | Ruggero Ferrario | Italy | a 0″ | 22 | Carlo Colombo | Italy | a 23’0″ | |

| Source: Museo Ciclismo | ||||||||

Strada’s two rides in Lombardia had been because the race organisers welcomed the publicity her presence brought them during two war-ravaged editions of their race. Once the war was over, they no longer needed her: the boys were back from the front. Of the 86 riders who started the 1919 Giro d’Italia, 42 of them were ex-armed forces. Strada was surplus to requirements.

Then, in 1924, La Gazzetta dello Sport needed Strada one more time. A war – with the teams – was raging, over the issue of appearance fees. Only this time Colombo and Cougnet didn’t need Strada to ride the Giro di Lombardia. They wanted her to ride the Giro d’Italia itself.

Next: Revenue sharing, 1924 style.

* * * * *

Sources: If your Italian is up to snuff and you’d like to learn more about Strada, seek out Paolo Facchinetti’s Gli Anni Ruggenti di Alfonsina Strada (The Roaring Years of Alfonsina Strada), which has also been translated in the Netherlands as Het Roerige Leven van Alfonsina Strada.

Strada’s story is also touched upon in the three Giro-related books to land last year: Bill and Carol McGann’s The Story of the Giro d’Italia – A Year by Year History of the Tour of Italy, Volume I, 1909-1970 (McGann Publishing), which is a valuable source of year-by-year race data; John Foot’s Pedalare! Pedalare! – A History of Italian Cycling, which succeeds in its attempt to try and see Italian cycling of the campionissimi era in a wider cultural context; and Herbie Sykes’ Maglia Rosa – Triumph and Tragedy at the Giro d’Italia, which is filled with wonderfully told stories of the men whose legends were made by the Giro and who have in turn forged the legend of a race that is often far more fascinating than its over-exposed French cousin.

Those three books are the main sources for the above, with additional information on Strada drawn from the Italian Cycling Journal and Radio Marconi blogs. The Giro di Lombardia stories can be found on Museo Ciclismo.

1 Comment

[…] 1924 cycling season. In the first five parts we’ve looked at the the 1924 peloton in general (part 1), the 1924 Giro d’Italia (part 2 + part 3), what happened to Alfonsina Strada (part 4) and […]