In the third part of this look at the 1924 cycling season, the first Grand Tour of the year, the Giro d’Italia, finally gets underway, without most of its major stars and with Alfonsina Strada among the ninety starters.

In the 1920s, cycling had but two Grand Tours. The Spanish were only slowing getting into gear, in 1924 launching a tour of the Basque Country. A Tour of Spain itself was still a long, long way off. For the two Grand Tours that did exist, the Tour de France and the Giro d’Italia, a comfortable formula had established itself: racing days alternating with rest days.

The racing days themselves were mammoth affairs, the shortest about the length of the longest stage in modern Grand Tours, the longest more than 400 kilometres. Riders would start in the dead of night, racing over roads that were little more than rock-strewn dirt tracks, to finish in the mid-afternoon, often in crowd-filled vélodromes, hopefully in time for the journalists covering the event to get their stories off so fans could spend the next morning reading about what had happened the day before. And fans did have to wait until the next morning to find out what happened, it was the 1930s before the Giro and the Tour went multimedia, with the arrival of radio.

The percorso of the 1924 Giro went like this:

| 1924 Giro d’Italia (3,613kms in 12 stages over 23 days – max 415kms, min 230kms, avg 301kms) |

||||||

| Day | Date | Partenza | Arrivo | Dist | Time | KPH |

| Saturday | 10-May | Milan | Genoa |

300kms |

11h02’03” |

27.19 |

| Sunday | 11-May | Giorno di Riposo | ||||

| Monday | 12-May | Genoa | Florence |

307kms |

11h52’36” |

25.85 |

| Tuesday | 13-May | Giorno di Riposo | ||||

| Wednesday | 14-May | Florence | Rome |

284kms |

10h56’06” |

25.97 |

| Thursday | 15-May | Giorno di Riposo | ||||

| Friday | 16-May | Rome | Naples |

249kms |

9h46’14” |

25.48 |

| Saturday | 17-May | Giorno di Riposo | ||||

| Sunday | 18-May | Potenza | Taranto |

265kms |

9h47’18” |

27.07 |

| Monday | 19-May | Giorno di Riposo | ||||

| Tuesday | 20-May | Taranto | Foggia |

230kms |

9h05’18” |

25.31 |

| Wednesday | 21-May | Giorno di Riposo | ||||

| Thursday | 22-May | Foggia | L’Aquila |

304kms |

12h47’27” |

23.77 |

| Friday | 23-May | Giorno di Riposo | ||||

| Saturday | 24-May | L’Aquila | Perugia |

296kms |

11h12’18” |

26.42 |

| Sunday | 25-May | Giorno di Riposo | ||||

| Monday | 26-May | Perugia | Bologna |

280kms |

10h47’26” |

25.95 |

| Tuesday | 27-May | Giorno di Riposo | ||||

| Wednesday | 28-May | Bologna | Fiume |

415kms |

17h29’12” |

23.73 |

| Thursday | 29-May | Giorno di Riposo | ||||

| Friday | 30-May | Fiume | Verona |

366kms |

18h15’54” |

20.04 |

| Saturday | 31-May | Giorno di Riposo | ||||

| Sunday | 1-Jun | Verona | Milan |

313kms |

12h51’21” |

24.35 |

| Source: Memoire du Cyclisme | ||||||

Alfonsina Strada, legend has it, was officially entered in the Giro under the name Alfonsin Strada, with the big reveal – He’s a she! – coming after the race had set off. The Italians love their polemica and really know how to stir it. Certainly the column inches Strada generated for La Gazzetta easily helped make up for the lack of big-name riders. And helped to sell lots of newspapers. Here was a point that the teams and their stars had overlooked with their attempt to extort more money from the race organisers: La Gazzetta was faced with a new rival, the Corriere dello Sport, and circulation was down. And, consequently, so too was profit. Not only could La Gazzetta not afford the extra costs the teams wanted to impose upon them but they also desperately needed a circulation boost. The scandals – a lack of stars and the Devil in a Skirt – gave them just that.

In both her Giri di Lombardia, Strada had finished at the back of the field. Little more of her was expected in the corsa rosa. Even La Gazzetta acknowledged, from the start, that this would be the case, saying:

Alfonsina doesn’t challenge anybody for victory, she just wants to show that even the weak sex can do the same as strong men. Might she be a vanguard for feminism that demonstrates its stronger capacity in order to demand the rights to vote in local or national elections?”

La Gazzetta could present her as an icon of feminism, but the truth was they were using Strada to create a spectacle, to give the tifosi something to get excited about in the absence of the likes of Costante Girardengo (Maino), Giovanni Brunero (Legnano), and Ottavio Bottecchia (Automoto). And a spectacle is exactly what Strada gave the Giro. La Gazzetta, describing Strada and the crowd that cheered her passing, had this to say of the woman “with a short baby haircut and even shorter shorts from which the hems of her jumper in particular protruded:”

She pedalled with self-confidence and cheer, like a schoolboy playing truant. The public that lined the streets in the passing villages immediately noted her with exclamations of wonder, the women in particular perhaps scandalised to see her like this […] hardly representing their sex.”

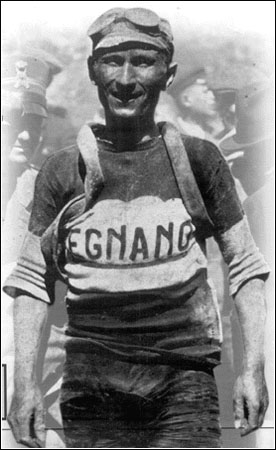

But, for Strada, the Giro was not just about spectacle. Every day – well, every other day – she still had to get from A to B. At the end of the first stage, 300 kilometres from Milan down to Genoa on the Ligurian coast, Strada was an hour off Bartolomeo Aymo’s stage-winning pace (eleven hours two minutes and three seconds, nearly ten minutes faster than second placed Federico Gay, of Alcyon). In the last three Giri, Aymo had finished third, second, and third (the first two with Legnano, the last with Atala) and already looked set to secure another podium finish as a minimum. Rolling home in fourth on the day, 18’39” down on Aymo, was the winner of the 1920 Giro, Gaetano Belloni, accompanied by his Legnano team-mate Giuesppe Enrici. That was the best Belloni could do in the 1924 Giro. As for Enrici, who’d stood on the bottom step of the podium in 1922, his first proper season in the pro peloton, well he was down, well down, on the day. But far from out.

For Enrici, the second stage was about pulling back some of that time lost on that first day. At the end of the second stage – 307 kilometres from Genoa to Florence – Gay had taken the stage, just ahead of Enrici, with Aymo ceding seven minutes and finishing down in fifth. The peloton itself was already whittled down to just sixty-five riders, thirty-five riders already no longer part of the race. Strada, a real stayer, wasn’t among the thirty-five, she was still riding on when others had fallen by the wayside. Slowly riding on, yes, but still riding and not always the last one home: arriving into Florence she was fifty-sixth and just over two hours behind Gay. The time differential hardly seemed of consequence to the tifosi. Of that day’s racing La Gazzetta noted:

In only two stages, this little lady’s popularity has become greater than all the missing champions put together.”

On the 284 kilometre run from Florence to Rome Strada was two and a half hours off the pace set by Gay, who again won the stage. Aymo was forced to abandon the Giro early, leaving Gay to take the lead, with a fourteen minute advantage over Enrici. The Giro would now be a straight fight between an Alcyon rider (Gay) and a Legnano rider (Enrici).

On the 249 kilometre sprint from Rome to Naples Strada was again more than two hours behind the stage winner, Zanaga. Gay put another couple of minutes into Enrici, extending his overall lead out to sixteen minutes. La Gazzetta, in its reporting of that day, noted how much attention Strada had received during the Giro’s stay in Rome:

“There was the usual hullabaloo around Alfonsina who arrived at the checkpoint in a new bright outfit. This woman is becoming famous. Yesterday some receptions were held in her honour. The good Romans gave her flowers, a new jersey and even a pair of ear rings. She is radiant.”

Back in those days Grand Tour stages typically started where the previous stage ended. In the 1924 Giro this was true, with the exception of the fourth and fifth stages: on the rest day between the two the riders had to travel south from Naples to Potenza, about 150 kilometres as the crow flies, by-passing along the way Mt Veseuvius.

Nothing much changed on the last of the southward bound stages, the run down to Taranto from Potenza. Ditto could be said – or not said – of the ride north up to Foggia. But the next two stages – into the heart of the Apennines, Foggia to L’Aquilla and L’Aquilla to Perugia – were where the 1924 Giro was won and lost.

On the first day in the Apennines Enrici put more than seventeen minutes into Gay, overturning his deficit and taking the overall lead with a margin of just one minute. The next day Enrici again won the stage and this time Gay ceded more than thirty-nine minutes to his rival.

As for Alfonsina Strada, well her Giro officially ended on that second day in the Apennines, 296 kilometres of racing that would have made a Flandrian weep: shitty roads and shittier weather. Strada crashed and thrashed her handlebars. A broom handle was used to effect emergency repairs (broom handles were often used in those days to effect emergency fork repairs – early cyclists were a resourceful crowd). But by the time Strada reached Perugia – four hours behind Enrici – the control was closed. Strada had been caught by the cut off. Colombo really wanted Strada to get to the finish in Milan – hell, she was selling newspapers – but he was overruled by the men in blazers, the commissaires declaring that rules is rules. Strada was off the 1924 Giro d’Italia.

The Apennines behind them, the remaining riders then faced a gentle sub-300 kilometre haul up to Bologna, followed by the mammoth 415 kilometre leg taking them eastward to Fiume on the Dalmatian coast, now in present-day Croatia but then still a part of the Kingdom of Italy. Into Bologna Enrici finished second, behind his Legnano team-mate Arturo Ferraro, with Gay ceding another eight minutes on the day. The fight back was not on. Into Fium it was Romolo Lazzeretti (Jenis) who took the stage, beating Legnano’s Ferraro and Alfredo Sivicci in a straight sprint. Gay tossed away another nine minutes.

From Fiume it was westward-ho and home to Milan via Verona, staying clear of the Dolomites, for a finish in the Vélodrome Semplone. Into Verona, Ferraro again took the stage win with Gay second on the day in a bunch sprint. And then it was Milan again, the end of the road, the Vélodrome Semplone. In a hotly-contested sprint, Giovanni Bassi – one of the proper isolati in the race, a man used to riding without team support – edged out Gay, only for both riders to be demoted for an irregular sprint, the victory then going to Legnano’s Sivocci, the seventh stage won by a Legnano rider. Enrici – born in Pittsburg but Piedmontese to the bone – took the title. A third place in his first season, a win in his third, boy but did that guy have a bright future ahead of him.

Half an hour after Bassi and Gay had battled for the final stage win, the Vélodrome Semplone again erupted in applause: Alfonsina Strada had just raced in, battling on despite her exclusion from the race. Following Strada’s disqualification in Perugia, Colombo had had a quiet word with her. There was business to discuss. She was helping him sell newspapers. Yes, here she was, battered and bruised, beaten by the race. But it didn’t have to end there. She could ride on, shadow riding the Giro, apart from the race but still a part of it. And for this service she would be paid, handsomely. While Colombo had refused to meet the teams’ demands for appearance fees, he was more than willing to pay Strada to just stay on her bike and keep the punters happy. There’s principles and then there’s commerce: commerce usually trumps principles.

So Strada rode out the remaining four stages, alongside two other riders who’d also been turfed off the race (in early Tours Desgrange had also allowed riders officially out of the competition to continue racing, on a daily basis). It’s claimed that Strada was the highest-earning rider in that year’s Giro, pocketing 50,000 lire for her efforts (remember, the overall prize fund was 100,000 lire).

That Strada was a draw for the fans is evident in the fact that, even when she was finishing way down on the leaders, the tifosi still awaited her arrival at the end of each stage, cheering her home. At Fiume, the race’s tenth stage, that mammoth 415-kilometre haul down the Dalmatian coast, by which time Strada was officially off the Giro but still shadow riding it alongside the peloton, the crowd waited for her to arrive before they left. Strada’s luck hadn’t improved: as in the Apennines she’d again crashed and arrived at the finish in a bad state and well down on the front runners. The tifosi didn’t care and showed their appreciation of her effort by lifting her off her bike: proving, if proof were needed, that sport isn’t just about winning. The next day, Fiume to Verona, a 366-kilometre haul that the peloton tackled at a sedate twenty kilometres an hour, Strada was just seven minutes down on the main bunch.

Strada’s popularity during the race was such that she spent a lot of time handing out photographs and signing autographs. The King, Victor Emmanuel III, sent her an official communication, congratulating her. Even Il Duce, Mussolini, wanted to muscle in on the act, declaring that he wanted to meet the Queen of the Cranks.

The following year the Darling of the Giro attempted to enter the corsa rosa again but – as with the post-War Giri di Lombardia – Colombo and Cougnet didn’t need her and the big teams and their star riders didn’t want her: to be upstaged by second-string riders was one thing, but to be upstaged by a woman was something entirely different. The Giro was still in dispute with the teams – Bianchi and Maino were still shunning the race – but the Queen of the Cranks had been usurped by Colombo and Cougnet’s new saviour: Emilio Bozzi.

As well as his Legnano squad, Bozzi – and his direttore sportivo, Eberardo Pavesi – now had the Wolsit outfit (after the second world war he would add Frejus to his portfolio of bike brands). The Wolsit and Legnano teams of 1925 were really just one team, with one team car to support them both. And what a team they were: Bozzi and Pavesi lost Enrici to Armor and Aymo to Alcyon but gained Costante Giradengo – the first campionissimo – from Maino. And they also gained a rider from La Française, a kid called Alfredo Binda. You’ll be hearing of him again before this is out.

Alfonsina Strada was the story of the 1924 Giro, a publicity coup for the race organisers in their fight against the revenue-sharing demands of the teams and the competition they faced from rival publishers. Enrici was a worthy winner of the race, a solid rider, but Strada’s fame has lasted far longer than his. Elsewhere in the 1924 cycling season – at the Tour de France, to be precise – it was to be the reporting of a French journalist, Albert Londres, that would last longest in public memory. But before turning to them let’s take a look at Strada herself, and what happened to the revenue sharing demanded faced by the Giro organisers.

Next: How Strada spent her 50,000 lire.

* * * * *

Sources: If your Italian is up to snuff and you’d like to learn more about Strada, seek out Paolo Facchinetti’s Gli Anni Ruggenti di Alfonsina Strada (The Roaring Years of Alfonsina Strada), which has also been translated in the Netherlands as Het Roerige Leven van Alfonsina Strada.

Strada’s story is also touched upon in the three Giro-related books to land last year: Bill and Carol McGann’s The Story of the Giro d’Italia – A Year by Year History of the Tour of Italy, Volume I, 1909-1970 (McGann Publishing), which is a valuable source of year-by-year race data; John Foot’s Pedalare! Pedalare! – A History of Italian Cycling, which succeeds in its attempt to try and see Italian cycling of the campionissimi era in a wider cultural context; and Herbie Sykes’ Maglia Rosa – Triumph and Tragedy at the Giro d’Italia, which is filled with wonderfully told stories of the men whose legends were made by the Giro and who have in turn forged the legend of a race that is often far more fascinating than its over-exposed French cousin.

3 Comments

[…] Strada, the woman who had helped save the 1924 Giro d’Italia, was buried in 1959. Ottavia Bottecchia, Henri Pélissier and Albert Londres – the other three […]

[…] looked at the the 1924 peloton in general (part 1), the 1924 Giro d’Italia (part 2 + part 3), what happened to Alfonsina Strada (part 4) and the role played by the Giro in the revenue-sharing […]

[…] the back of the race. In the 1924 Giro d’Italia, the story of the cut-off was illustrated by Alphonsina Strada’s misfortunes on the road into Peruggia and her expulsion from the race. In the 1955 Tour there’s the story of Shay Elliott nursing […]