Having looked at the version of the Tour de France that was reported at the time (part 1 + part 2), we now look at some of the explanations and justifications offered for how the 1996 Tour de France unfolded.

Two questions need to be asked here about the 1996 Tour de France. The first is: what had happened to Miguel Induráin? The other: what had happened to Bjarne Riis?

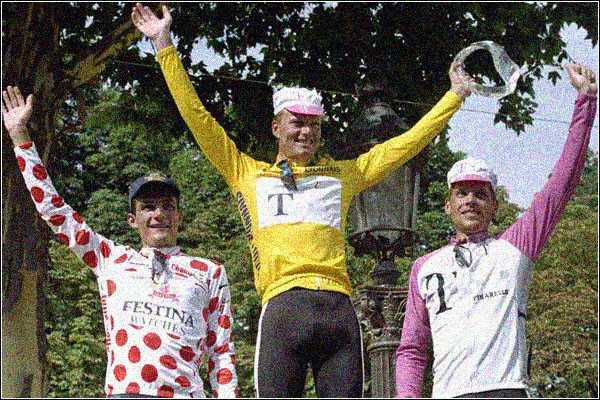

But before turning to those questions let’s consider one other question that ought be asked: where the hell had the Telekom team – which ended the Tour with the top two steps of the podium and the maillot vert as well as the maillot jaune along with what is today the maillot blanc for the best rider under twenty-five – come from?

Hennie Kuiper was the boss of the squad back in 1991 when the Telekom sponsorship began. Since he’d hung up his wheels at the end of the 1988 season Kuiper had been running the small Stuttgart squad and, in 1990, had seen his riders bag stages in the Nissan Classic and the Vuelta a España as well as overall glory in the Herald Sun Tour and De Panne, with Markus Schleicher, Erwin Nijboer, and Udo Bölts bringing home the booty. When the team became Telekom in 1991 it was with the same core of riders as the old Stuttgart squad. Their sole win of note that first season was Ad Wijnands’ overall victory in the Etoile de Bessèges.

The following year Kuiper was out and on his way to Motorola, and Walter Godefroot – the former Belgian pro who’d sparred with Eddy Merckx – was brought on board to boss the squad along with Frans van Looy. The roster was improved, with the addition of riders like Christian Henn and Jens Heppner, who would remain part of the team’s core for the next few seasons, along with proven talents like Uwe Ampler, Etienne de Wilde, and the Madiot brothers Marc and Yvon. Even if these older riders didn’t bring home results they were the sort who would help the squad get invitations to some important races. Bölts won them a stage in the Giro and that was about it for the year.

For 1993 Godefroot strengthened the team further with the addition of riders like Rolf Aldag, Bert Dietz, Brian Holm, Mario Kummer, and Stefan Wesemann. Two sprinters from opposite ends of the age spectrum also came on board: the thirty-two-year-old Olaf Ludwig and the twenty-two-year-old Erik Zabel. Between Aldag and Ludwig the team bagged stages in the Tour Méditerranéen, the Tour de Romandie, and the Tour de France. The following year Rudy Pevenage joined the management team. Axel Merckx came on board for the one season (the team rode Eddy Merckx bikes). Jens Lehman joined as a stagiare at the end of the season but didn’t stick around. But the key signing who did stick around was a twenty-year-old kid from Rostock: Jan Ullrich. Zabel delivered wins in the short-lived Classic Haribo as well as the sprinter’s Classic, Paris-Tours. Things were beginning to click into place.

In 1995, with no major additions to the squad, Zabel delivered stages in the Tour de Suisse and the Tour de France, with Dietz and Henn bringing home stages in the Vuelta a España. And then came the big breakthrough in 1996. As well as switching from Eddy Merckx’s bikes to Pinarello’s pretty little ponies – on which Pedro Delgado and Miguel Induráin had ridden to victory in five of the previous eight Tours – the German little team that couldn’t added Bjarne Riis to their roster.

Riis’s podium place in the 1995 Tour – and a top twenty and a top ten in the two Tours before that – were in his favour, but his age (he was then thirty-one) made him a risky choice. But at least his podium finish in 1995 would probably make it easier to get an invite to the Tour. Riis was also a driven man. As a kid he’d won early and often. As he grew through his teens, though, he didn’t seem to mature as quickly as his peers and the wins dried up. He’d had to scrabble hard to get a place in the pro ranks, signing for Lomme Driessens’ Roland squad and then going through one-year contracts with Lucas and Toshiba before falling into the orbits of Cyrille Guimard and his faltering vedette Laurent Fignon. At Super-U and Castoroma Riis matured and served as Fignon’s domestique. His reward was a stage win in the 1989 Giro d’Italia.

When Fignon split with Guimard, Riis moved on to the Italian Ariostea squad bossed by Giancarlo Ferretti. Two years there saw him adding another Giro stage to his palmarès along with a stage in the Tour. When Ariostea pulled their sponsorship at the end of 1993 Riis moved on to Gewiss, bossed by Emmanuele Bombini, where he added another stage win in the Tour to his record as well as that podium finish. But Gewiss was not a happy home for the Dane, not with Evgeni Berzin as a teammate. With the Russian on the rise Riis saw a future in which he’d be a domestique once more, and so he scarpered at the end of his two-year contract. When Godefroot dangled a contract with the right number of zeroes on it in front of his nose, Riis signed for Telekom, where there were no visible threats to his leadership and he could count on the undivided devotion of his new teammates in the years to come. That was the Dane’s plan anyway.

Now let’s get back to those other two questions, the ones about Induráin’s fall and Riis’s rise.

Various people have offered various explanations for Induráin’s Tour sans. There was the fringale on Les Arcs: the Spaniard had simply forgotten to eat. There was the weather: in the Alps it was too cold, on the Hautacam it was too hot. There was his weight: some say he’d gone into the Tour above his ideal race weight, others say the rainy conditions in the first week had bloated him as he retained water like a sponge. For sure, Induráin was no Bibendum, but in cycling’s size-zero obsession every kilo – every gramme – counts. And, when you’re six foot two and horsing eighty kilos up every claim, excess baggage comes at a very heavy cost. On a ten-kilometre climb, one kilo of excess weight can cost a rider a minute in time. Or so the stattos say, anyway, and you should never argue with a statto; they’ll only baffle you with bullshit.

Two races after the 1996 Tour help put Induráin’s Tour into context. At the Olympic Games in Atlanta the Spaniard was back on form, bagging the gold in the individual time trial. Then he turned up for the Vuelta a España which, the year before, had switched to its new Autumn calendar slot. Induráin’s relationship with his national Tour was somewhat fractious. Since his second-place finish in 1991 – when the Vuelta was still run off in Spring – Induráin had avoided the Spanish Grand Tour. Banesto put a gun to his head and told him he had no choice but to ride it in 1996.

So Induráin rode the Vuelta. On the first hard day in the high hills, Induráin served up a repeat of his Les Arcs défaillance with a pájara on the Alto de Naranco, in Asturias, where in the space of the final two kilometres he surrendered a minute to his ONCE rivals Laurent Jalabert and Alex Zülle. The next day was due to finish on the Lagos de Covadonga, but Induráin was already four minutes down as the peloton climbed the Fito. Before the base of the Covadonga itself the Spanish champion pulled out of the race and effectively ended his career.

As for Riis, all sorts of explanations have been offered for the transformation of a domestique into a Tour winner. Induráin himself had gone the same route, spending the first few years of his career working for others – especially Pedro Delgado – before finally, at the age of twenty-six, becoming the boss. The only real difference between Induráin and Riis was in when they’d matured: the Dane was three months older than the Spaniard but hadn’t got his chance to lead until he had turned thirty. Riis had simply taken longer to come of age.

Do the time losses and gains in the Alps matter much when looking at where Induráin lost the Tour and Riis won it? Yes and no. Riis exited the Alps with just a forty-second cushion over Berzin, time that could easily be lost in either the Pyrénées or the penultimate day’s time trial. But Riis had delivered a psychological blow to his opponents in the Alps, especially on the truncated stage to Sestrières.

As for Induráin, the three minutes lost to Riis on Les Arcs plus the minute lost the next day in the time trial up to Val d’Isère and the half-minute lost up to Sestrières were, to say the least, unusual. But, with the Pyrénées and that final time-trial still to come, it was not inconceivable that the Spaniard could still come out on top. Richard Virenque (Festina) only had a minute on him, a minute he could (and would) surrender in the time trial. Peter Luttenberger (Carrera) and Jan Ullrich (Telekom) may have had two and three minutes on Induráin, but they were kids – twenty-three and twenty-two – and kids break easily, physically and mentally. As for Abraham Olano and Toni Rominger (both Mapei), Evgeni Berzin (Gewiss), and Riis, well Induráin had cracked each of them in the past and could still crack them in the Pyrénées. Maybe it’s true that Induráin was unlikely to win the Tour exiting the Alps but it’s also true that his key rivals could still throw it all away. Once the Spaniard was there to take advantage of that then, yes, he could still win the Tour. That’s the key to defensive cycling: put them under pressure and wait for your rivals to crack.

After the Hautacam, though, the 1996 Tour was all but over. So what had really happened on the Hautacam? Again, the explanations vary. Induráin’s previous Tour victories, some would remind you, were based on defending time gained in time trials and guarding his losses in the mountains. Letting his rivals tire and exhaust themselves trying to crack him, and then profiting from their efforts.

The more obvious excuse for Induráin’s collapse on the Hautacam was that he simply couldn’t cope with Riis’s constant changes in paces. Had Induráin simply let Riis go and climbed at his own rhythm, who knows what the outcome would have been. Perhaps had Induráin paid more attention in his apprenticeship years he would have seen this. In the 1987 Tour Pedro Delgado had played on Stephen Roche’s climbing weakness by attacking him on the climb to La Plagne. Roche simply let Delgado go and worked up the climb at his own rhythm, ceding just a small amount of time to his Spanish rival at the finish. But Induráin allowed Riis to dictate an unsteady rhythm at the base of the Hautacam and paid the price. In his years of domination Induráin had grown accustomed to watching his rivals wear themselves out trying to shake him and simply assumed – hoped? – that the same would happen again.

What had happened to Riis on the Hautacam? The attack itself was almost as daring as the manner in which it was carried it out. Riis was, after all, in the yellow jersey and even by then cycling was in thrall to defensive tactics. According to the rules of catanaccio cycling, Riis was supposed to sit back and wait for the others to crack and only then put the boot in. But Riis had paid attention during his own apprenticeship years. Back in 1989 he’d been Laurent Fignon’s domestique and stood on the Champs Élysées on that infamous final Sunday afternoon in the Tour. Riis had seen Fignon struggling to match Greg LeMond’s split-times throughout the time trial and watched in horror as the Frenchman paid the price of riding someone else’s race and pedalled squares. He watched the American cry tears of joy and the Frenchman tears of loss when it was all over. (And he and his team-mates had cried, too, at the loss of their share of the winner’s purse.) Riis was there, too, for the autopsy that followed. Was it the saddle sores that had lost Fignon the Tour? Fignon’s aerodynamically-inefficient ponytail combined with LeMond’s aerodynamically-efficient helmet and tri-bars? Or was it that Fignon simply hadn’t put the boot in when he should have in the Alps? Whatever it was, Riis learned not to make the same mistakes himself.

And so, in the maillot jaune and with advantages of between one and four minutes on his key rivals at the start of the day, Riis attacked on the Hautacam. And it wasn’t just the memory of Fignon that played a role that day. At the end of the stage Riis thanked not just his Telekom directeur sportif, Walter Godefroot, but also the former champion Fignon. The Frenchman, the Dane said, had been offering him advice throughout the race. And Fignon’s advice was simple: attack, attack, and attack again. The sacred principles of la course en tête.

So Riis attacked in yellow. And kept attacking. But where had the power for those attacks come from? Isn’t that really the big question of that day on the Hautacam? Riis flew up the climb like a Ferrari blitzing the track in Mugello. How had a donkey turned into a Thoroughbred? The answer to that, too, was simple: acupuncture. Riis used the services of an acupuncturist, John Boel, who travelled on the 1996 Tour as part of Riis’s entourage. And Boel knew of an area below the knee he called the three mile point. Jab a pin in it properly, he claimed, and you’ll get a new source of energy that’ll carry you three miles beyond where you normally give up. Riis certainly believed him. And sometimes believing is enough to make something true.

On the Hautacam that day, as well having Boel press the turbo-charge button below Riis’s knee, the Dane also played some mind games with his opponents. Riis was one of that rare breed of cyclists who actually paid attention to the machine he propelled. While Toni Rominger was farting around with switching his brake lever over – and thus propelling himself arse over tit when instinct kicked in one day and he pulled the wrong one to avoid an errant rider in front – Riis was thinking how he could use his bike as a psychological weapon. And on the day of the Hautacam stage he had his wrench monkey fit a smaller than normal outer ring. When Riis went for it on the Hautacam, spinning that big ring with ease, his rivals saw a man possessed by supernatural strength. What they didn’t notice was that he was riding about the same gear they were.

Winning and losing bike races, some would argue, really is as simple as all that.

1 Comment

[…] justifications offered by some for Miguel Induráin’s loss and Bjarne Riis’s victory (part 3). Now let’s take a peek at the alternative […]