With the 2012 Tour de France gearing up for its start in Liège we return to our story of the 1924 cycling season. In the first five parts we’ve looked at the the 1924 peloton in general (part 1), the 1924 Giro d’Italia (part 2 + part 3), what happened to Alfonsina Strada (part 4) and the role played by the Giro in the revenue-sharing debate (part 5). We now turn to the other Grand Tour, some more heroes of our sport, and one of cycling’s perennial problems: doping.

Pick up any Tour guide – you’re spoiled for choice, the bookshop shelves creak under the weight of Tour-centric texts – and you’ll typically find the 1924 Tour reduced to two stories: les forçats de la route and the short life and mysterious death of Ottavio Bottecchia.

Les forçats de la route is where, for me, this look at the 1924 cycling season started. Albert Londres had covered the whole of the 1924 Tour, yet just about all most of us know of those reports is that one story, that day in the Café de Gare in Coutance when Henri and Francis Pélissier, along with their team-mate Maurice Ville, spat on the soup and showed Albert Londres just what it took to ride the Tour de France. Yes, it was an important story. But what of what else Londres wrote, what did his other reports from the 1914 Tour have to say?

Those other reports appeared in Le Petite Parisien over the course of the Tour. Today they would be described as colour pieces, supplemental reports which give colour and depth to the basic story of what happened as the peloton raced between A and B. Anyone reading Londres’ reports would already have been familiar with what was actually happening in the race. Disconnected from the actual race, Londres reports lose something (similar to the way books like Bradley Wiggins’ On Tour or Nicolas Roche’s Inside The Peloton lose something). So it became necessary to read, alongside Londres’ reports, an account of what happened in the 1924 Tour. That, somehow, then led me to looking at what else was happening in the world of cycling in 1924.

Some people tend to get a little bit sniffy when it comes to Albert Londres and his Tour articles for Le Petite Parisien. Londres was an outsider, what could he possibly know of our sport? Our sport is far too complex for outsiders to properly understand. Some people really do need a slap around the head with a rolled up newspaper. The whole point of getting outsiders to look at our sport is so that we can see it as others see it.

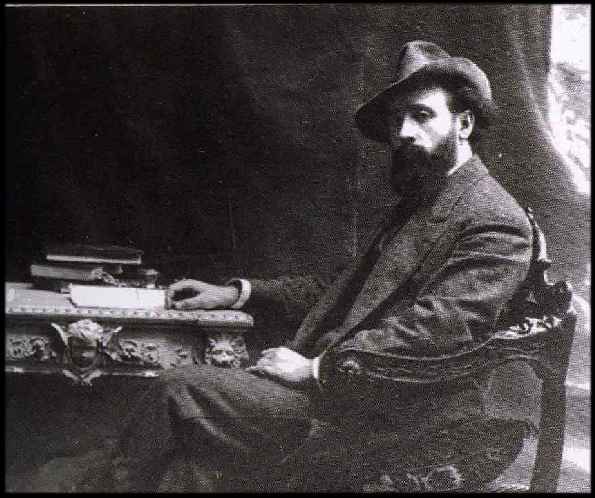

More importantly, Londres was far from ignorant when it came to cycling. He was far from ignorant when it came to most of the subjects he reported. He was, in today’s parlance, a crusading, investigative reporter. And that – by 1924 – had earned him a considerable reputation in France. Each of his major investigations for Le Petit Parisien was published in book form. In 1920 there had been Dans La Russie Des Soviets, Londres’ look at Russia after the October Revolution. Then came his most famous work, Au Bagne, an investigation into the French penal colonies in Cayenne and in Guyana (in the latter, the Iles de Salut, which encompassed Devil’s Island). The story Londres told shocked a French nation which thought itself civilised.

The same year that Londres reported on the Tour de France he published Dante N’Avait Rien Vu. Its title – Dante saw nothing – suggested that French military battalions in North Africa were even worse than any of the circles of hell depicted in Dante’s Inferno. And, before turning his attention to the Tour de France, Londres had already written Chez Les Fous, an investigation into conditions in French mental institutions. To cover this story Londres had had himself incarcerated in one such asylum in order to tell his story properly.

How true, then, were Londres’ reports from the 1924 Tour? The easiest way to answer that is to show by example. And in order to do so, we need to look at the 1924 Tour.

By 1924, Henri Desgrange’s Tour de France had established itself in the minds of the French public and the shape and structure of the race was pretty firmly fixed. Starting in Paris it headed west and then south in an anti-clockwise circuit of the hexagon, taking in the Pyrénées and then the Alps. As with the Giro d’Italia, racing days alternated with rest days.

| 1924 Tour de France(5,425kms in 15 stages over 29 days – max 482kms, min 275kms, avg 362kms) | ||||||

| Date | Day | Départ | Arrivée | Dist | Time | KPH |

| 22-Jun | Sunday | Paris | Le Havre | 381 kms | 15h03’14” | 25.31 kph |

| 23-Jun | Monday | Répos | ||||

| 24-Jun | Tuesday | Le Havre | Cherbourg | 371kms | 14h34’31” | 25.45 kph |

| 25-Jun | Wednesday | Répos | ||||

| 26-Jun | Thursday | Cherbourg | Brest | 405kms | 15h44’00” | 25.74 kph |

| 27-Jun | Friday | Répos | ||||

| 28-Jun | Saturday | Brest | Les Sables d’Olonne | 412kms | 16h28’51” | 25.00 kph |

| 29-Jun | Sunday | Répos | ||||

| 30-Jun | Monday | Les Sables d’Olonne | Bayonne | 482kms | 19h40’00” | 24.51 kph |

| 01-Jul | Tuesday | Répos | ||||

| 02-Jul | Wednesday | Bayonne | Luchon | 326kms | 15h24’25” | 21.16 kph |

| via the Col d’Aubisque (1,709m), Col du Tourmalet (2,115m), Col d’Aspin (1,489m) and Col de Peyresourde (1,569m) (Pyrénées) | ||||||

| 03-Jul | Thursday | Répos | ||||

| 04-Jul | Friday | Luchon | Perpignan | 323kms | 12h40’18” | 25.49 kph |

| via the Col des Ares (797m), Portet d’Aspet (1,069m), Col de Port (1,249m) and Puymorens (1,915m) (Pyrénées) | ||||||

| 05-Jul | Saturday | Répos | ||||

| 06-Jul | Sunday | Perpignan | Toulon | 427kms | 17h04’45” | 25.00 kph |

| 07-Jul | Monday | Répos | ||||

| 08-Jul | Tuesday | Toulon | Nice | 280kms | 11h52’08” | 23.59 kph |

| via the Col de Braus (1,002m) and the Castillon (706m) (Les Alpes Maritimes et de Provence) | ||||||

| 09-Jul | Wednesday | Répos | ||||

| 10-Jul | Thursday | Nice | Briançon | 275kms | 12h51’07” | 21.4 kph |

| via the Col d’Allos (2,250m), Col de Vars (2,110m) and Col d’Izoard (2,361m) (Alpes) | ||||||

| 11-Jul | Friday | Répos | ||||

| 12-Jul | Saturday | Briançon | Gex | 307kms | 12h31’51” | 24.5 kph |

| via the Col du Galibier (2,556m), Télégraphe (1,566m) and Aravis (1,498m) (Alpes) | ||||||

| 13-Jul | Sunday | Répos | ||||

| 14-Jul | Monday | Gex | Strasbourg | 360kms | 15h51’02” | 22.71 kph |

| via the Col de la Faucille (1,323m) (Jura) | ||||||

| 15-Jul | Tuesday | Répos | ||||

| 16-Jul | Wednesday | Strasbourg | Metz | 300kms | 11h36’27” | 25.85 kph |

| 17-Jul | Thursday | Répos | ||||

| 18-Jul | Friday | Metz | Dunkerque | 433kms | 20h17’51” | 21.33 kph |

| 19-Jul | Saturday | Répos | ||||

| 20-Jul | Sunday | Dunkerque | Paris | 343kms | 14h45’20” | 23.25 kph |

Officially, 182 riders were entered for the 1924 Tour, of whom 157 actually took the start. The Tour back then had three categories of riders: premier, deuxime and touristes-routiers. The first two were the hard-core pros, allied to trade teams of different sizes. The touristes-routiers were the isoles of old, the independent riders who looked after themselves as they trundled around France.

Among the starters at the 1924 Tour were five former winners of the grande boucle: Henri Pélissier (1923), Firmin Lambot (1919 and 1922), Léon Scieur (1921), Philippe Thys (1913, 1914 and 1920), and Odile Defraye (1912). (And, in that 1924 Tour, taking the line were three men – Ottavio Bottecchia, Lucien Buysse and Nicolas Frantz – who, between them, would win the next five Tours. Think about that a moment: a Tour with eight past and future Tour winners in it.) The big buckle was also playing host to a couple of champions of the corsa rosa: Giovanni Brunero (1921 and 1922) and Giuesppe Enrici (1924). Yes, the just-crowned Giro champion was riding his second Grand Tour of the year, with just three weeks between the end of one and the start of the other.

That someone should ride both Grand Tours was not particularly unusual. Alongside Enrici in the 1924 Tour were his Legnano team-mates Bartolomeo Aymo, Arturio Ferrario, and Ermanno Vallazza, who had all started the Giro with him. And there were also the likes of Gianbattista Gilli, Ottavio Pratesi (Ostende), Giovanni Rossignoli, Enrico Sala (Ganna), and Luigi Ugaglia, who had also all started the Giro.

How unusual was it for a just-crowned Giro winner to take on the Tour? We know that it wasn’t until the arrival of Fausto Coppi that the Giro-Tour double was pulled off. But, before 1949, how many times had that even been a possible outcome, how many times had a just-crowned winner at the Giro turned up for the Tour?

Luigi Ganna started the Tour in 1909, but abandoned on the third stage. In 1919, Costante Girardengo had been entered in the Tour, but didn’t take the start. Gaetano Belloni took the start in 1920 but didn’t finish the first stage. And that was it. So Enrici’s participation was quite unusual.

Post-1924 – and before Coppi in 1949 – four just-crowned Giro winners tackled the Tour: Francesco Camusso in 1931 (DNS stage 10); Antonio Pesenti in 1932 (who was the first reigning Giro champion to finish the Tour, ending the race just off the podium, in fourth, and with one stage victory to his name); Vasco Bergamaschi in 1935 (DNF stage 15, after winning one stage); and Gino Bartali in 1937 (DNF stage 12a, having won one stage and held the maillot jaune for two stages). All of which – for me at least – helps add perspective to Coppi’s 1949 Giro-Tour double: before him, only seven had tried, of whom only three had even won stages and only one had managed to lead the race. Coppi’s achievement – the stage wins as well as the overall victory – really did rewrite the history books. (If you want to know how often the Giro-Tour double was even a possibility after Coppi, ask a statto.)

* * * * *

One of the biggest oddities about cycling in those days was start times. Organisers usually wanted their races to finish in the mid-afternoon: fans would be on hand and journalists would have enough time to write their story up, briefly for an evening edition, in more detail for the morning edition. Start time, then, was based on desired end time, taking into account stage duration. With stages running three and four hundred kilometres, start times were early. Very early. Throughout the 1924 Tour they ranged between ten at night and six in the morning.

So it was that the 1924 Tour rolled off from Luna Park in Paris at a quarter to one in the morning of Sunday, June 22nd. The first hour and a quarter of the 381 kilometre haul west to Le Havre was neutralised, the real race not commencing until two o’clock, when the riders reached Argenteuil.

Londres opened his report of the first stage with a scene from Porte Maillot, on the western outskirts of Paris, 11.30 at night and riders still in restaurants, their last supper before setting out on the Tour de France. Londres’ impression is of a Venetian festival, the riders’ jerseys making them seem to him like festive lanterns. A last drink and the riders leave, cheered off by a crowd of onlookers. And this is what Londres finds most striking about the Tour’s start: the crowds cheering it on its way. Here he is just after the off:

For my part, I took, at one in the morning, the road to Argenteuil. Respectable gentlemen and ladies were pedalling through the night: I would never have supposed there were so many bicycles in the département of the Seine.”

When the riders arrive in Argenteuil, night seems to become day:

Then, the suburb came alive: the windows came alive with spectators dressed for bed, people crowded the crossroads impatiently, old women, who normally take their sleep with the sun, waited in front of their doors, sat on chairs, and if I didn’t see infants on the tit, it’s most likely that the night hid them from me.”

Shortly after the off Londres comes across a rider on the pavement, fixing a puncture. He stops to chat, when from behind suddenly comes a volley of insults. Quickly Londres realises he is the target: his Renault is blocking the road, and behind him is a passionate throng of people trying to follow the race.

An hour later – the time now about 3.30 – and the road is travelling through a forest, the passage lit by braziers on either side of the road, reminding Londres of tribes watching for the presence of a lion. Londres espies among the onlookers a couple dressed for the Opéra. These were Parisians, awaiting the passage of les géants de la route.

Day breaks and it is clear that, on this night, the people of France haven’t slept a wink. The entire province stands at its doorways, hair in curlers.”

Riders have been falling by the wayside, suffering punctures, already suffering stomach cramps. Then Londres comes to a level crossing which splits the peloton: five riders who missed the break slip beneath the barrier just as the train arrives, crossing ahead of it and then pedalling off into the waking day.

The towns roll by. Montdidier, Berthacourt, Flixecourt, Amiens. More crowds cheering:

– Vas-y, Henri!.. Vas-y, Francis!

– Vas-y, gars Jean!

– Vas-y, Ottavio!

– Thys! Thys! Hardy!

– Vas-y, ‘la pomme!’

Henri and Francis are the Pélissiers. The boy Jean is Alavoine (brother to Henri, one of the many cyclists to die during the Great War). Ottavio is Bottecchia. Thys and Hardy are Phillipe Thys and Emile Hardy, two Belgians. And la pomme, the apple, is Eugène Dhers.

Onwards. Abbeville. Le Tréport, Dieppe, Fécamp. Finally, Le Havre. Fifteen hours after leaving Paris. Twenty riders sprinting for the bonifications. Bottecchia takes the stage, the three minute time bonus and the first maillot jaune, ahead of his Automoto team-mate, Maurice Ville. (Bonifications had been introduced the year before, then at two minutes per stage for the first rider home, to spice up dull stage finishes. So impressed with them was Desgrange that, for 1924, he increased the bonus to three minutes.) Five hours after Bottecchia et al, the last rider rolled in. Twenty riders already eliminated, 381 kilometres down, 5,044 to go.

After a rest day in Le Havre, the riders set out for the second stage, 371 kilometres from Le Havre of Cherbourg, again getting underway in the black of night. Coming into Cherbourg a group of six riders got a twenty-four second advantage on the peloton and Peugeot’s Romain Bellenger took the stage (and the bonifications) ahead of Ville and Frantz. Bellenger had lost time on the first stage – he was in the chase group, three minutes down on the bunch – and, though Bottecchia finished in the main group, twenty-four seconds down on the day, the Italian still held onto his maillot jaune, his three minute advantage over Ville whittled down to 2’36”. Another 371 kilometres down, 4,673 remaining, 125 riders left to ride them.

Next: Coutances.

No Comments