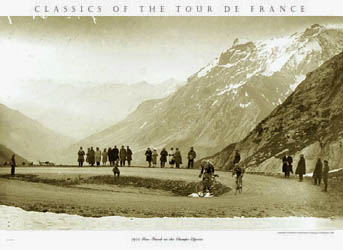

In this ninth part of our look at the 1924 cycling season we wrap up the 1924 Tour de France – and Albert Londres’ reporting of it – as the riders tear through the Alps and then onward to Paris.

The Tour entered the Alps with a 275-kilometre trundle from Nice to Briançon, taking in the Col d’Allos (2,250m), the Col de Vars (2,110m), and the Col d’Izoard (2,361m). With a comfortable lead Ottavio Bottecchia (Automoto) could afford to take things easy. Giovanni Brunero (Legnano) and Nicolas Frantz (Alcyon) got away on their own, the man from Luxembourg leading over all three climbs, but the Italian pipping him to the post in Briançon, taking the stage and the three minutes in bonifications. Romain Bellenger (Peugeot) rolled home third, 8’32” down, with Bottecchia alone another 1’23” behind him. There was no change in the podium positions, but Frantz was now down to ‘just’ 41’52” off the lead, Brunero another 3’45” behind. A lot of time today, but back then the sort of time that could still be made up were Bottecchia to have a nightmare day.

Two days later the racing resumed and the peloton tackled the Col du Galibier 2,556/2,645m), the Télégraphe (1,566m), and the Aravis (1,498m). Bartolomeo Aymo (Legnano) lead them over the Galibier and the Télégraphe, with Brunero leading over the Aravis, but the peloton arrived as one into Gex, 307 kilometres after leaving Briançon. Frantz took the stage and the three minutes time bonus, cutting his deficit on Bottecchia to 38’52”, Brunero now 6’45” behind him.

Londres’ report from the Alps reads like many of the race reports of that time:

Crossing these cols, they seemed no longer to be pushing on the pedals but tearing up huge trees by the roots, heaving with all their might at something invisible hidden deep in the earth, something that refused to budge; grunting ‘Ghanh … Ghanh …’ like bakers kneading their dough in the middle of the night. I didn’t speak to them; I knew them all but they wouldn’t have replied. When their eyes caught mine, it reminded me of a dog I had, staring imploringly at me, just before he died, because he was so profoundly sad at having to leave this earth. Then they lowered their eyes over the handlebars once more, and rode on, their gaze fixed to the road as if to find out whether the drops of liquid they were sprinkling over its surface were sweat or tears. This spectacle is part of what they call pleasure. That’s what the regional papers have decided it is. The people of the Dauphiné and Savoie départments will be setting out for the Galibier tonight at 12.45am. At the summit they’ll be able to get a cold supper and a glass of champagne for 45 francs all-in.”

On the descent of the Lizard, Londres witnessed a crash:

One of them brakes, zig-zags across the road … he’s going to go over the edge, he hurtles into the rock face, which planes a slice off his leg, but the rock brings him to a halt. I go over to him. His chain is broken.

– I had a small lead today. What a disaster. […] How am I going to mend that? I’d need an anvil.

He finds one big stone, one small: the big one for an anvil, the smaller for the hammer.

– If I can fix it, I’ll get drunk at the finish.

The repair doesn’t work.

– Something like this and you have to abandon.

“He’s a routier, [Giuseppe] Ercolani, a native of Froges [near Grenoble]. His wife’s about to have a baby.

– If it’s a boy, I’m going to call him Benjamin.

– Why?

– Because I’m the Benjamin of the Tour [the youngest rider]. I’m twenty-one.He succeeds in repairing the chain. ‘I’m happy,’ he says.

Other routiers go past downhill. It reminds him of his unhappiness.

– I started well today. I could have moved up a bit in the classification … anyway, now I’m back on course.

His chain fixed, as he puts his wheel back on he asks me:

– ‘You’re not a doctor as well, are you? You’d be able to tell me why the baby hasn’t arrived yet. I ordered everything, all the medicine, from the pharmacist before I left. It’ll go bad.

He leaps into the saddle.

– Ah, they won’t let me ride the Tour de France again. I’m too young; it’s cleaning me out. I’ll come back when I’m 25.

But he rides off, quick as a zebra who’s spotted a creepy lion. If Ercolani doesn’t get a telegram in Gex, I’ll forge one for him: the anxiety about the baby has gone on too long.”

No sooner has Ercolani set off than Londres comes across another rider in distress, Henri Collé, whose exchange with Baugé, the Marshal, Londres had reported a few days earlier. Collé has collided with a wagon and is out of the race. Coming from Geneva he had been looking forward to the reception that would have awaited him in Gex, fourteen kilometres over the border from his home town. Collé is upset:

What stinking luck. I was keeping something in reserve for the day after tomorrow. […] What rotten luck, mister, what rotten luck. […] This job’s a death ride. I only hope they still make a collection for me in Geneva.”

That was one of the attractions in riding the Tour: passing through or near to your home town and raising money there. For a few stars of the sport, international fame was a possibility. National fame could be achieved by quite a few riders, but for most the best they could hope to be was to become a local hero. That alone was often enough to keep them riding. Certainly it was better than working the family farm, or being a labourer.

Londres put Collé and his bike into his Renault and drove him to the finish:

What’s to become of a man that can’t ride any further? I give him a lift in my car. In accepting, Collé has, apparently, committed a grievous infraction. When a rider can no longer ride he must walk. Otherwise, he gets hit with a 500 franc fine. In his place I’d have killed myself on the spot. That way there’d be no infringement of the rules.”

Driving to Briançon Londres witnessed another incident which adds more to his picture of how inhuman bike racing back then could be:

Ahead of us is the lanterne rouge, the name they give the man who is last overall. It’s [Augusto] Rho, alias d’Annunzio. Difficult to say whether Rho is skinnier than he’s stubborn. He is replacing a tyre and appears to be deep in thought.

– What are you thinking about?

– I’m thinking about signor Bazin …Bazin is the timekeeper. At twenty-one hours, forty-one minutes and 3.35 seconds, Monsieur Bazin presses a small object under his table, a timepiece which cost 2,500 francs. Then he calls out: ‘Gentlemen, the control is closed.’ He might see d’Annunzio three metres away, crawling in on his stomach and, with an exaggerated shrug of desperate commiseration, signal that he is not going to bend the rules. Monsieur Bazin knows the vital significance of a tenth of a fifth of a second. Monsieur Bazin is a sort of cuckoo who inhabits a clock.”

The Bazins of the Tour still exist and riders still have to race against him. Few cycling biographies today are complete without the rider telling a tale of the day they had to race against the cut-off, suffering alone well off the back of the race. In the 1924 Giro d’Italia, the story of the cut-off was illustrated by Alphonsina Strada’s misfortunes on the road into Peruggia and her expulsion from the race. In the 1955 Tour there’s the story of Shay Elliott nursing Brian Robinson to the finish, only for both to be outside the cut-off, the Irishman sent home, the Briton allowed ride on having started the day inside the top ten riders. Pretty much every Tour produces at least one such story.

The Alps behind them, the Tour entered its final week and the race swept from Gex to Strasbourg, taking in the Col del la Faucille (1,323m) en route, which the peloton crossed as one. Into Strasbourg Frantz led home a group of four which contained Bottecchia. The three minutes in bonifications allowed Frantz to close to within 35’52” of the Italian. Brunero, who had won the Giro in 1921 and 1922, lost 4’50” on the day, finishing outside the top ten, but still held on to third place, now 50’27” off Bottecchia and 14’35” off Frantz.

Strasbourg to Metz, a 300-kilometre haul, saw Armor’s Arsène Alancourt take the stage, 2’38” ahead of Peugeot’s Georges Cuvelier. Frantz led home a small group, 3’09” down on the day but 3’26” up on Bottecchia, who could afford to dawdle: even at the end of the stage Frantz was still 32’26” in arrears. Brunero rolled home another twenty seconds down on Bottecchia but held on to his podium position.

The penultimate day’s racing saw the riders hauling their tired bodies the 433 kilometres from Metz to Dunkerque, setting out just as the clock struck midnight. In 1919 these roads scuppered any hopes Eugène Christophe had of overall victory. Le Viuex Gaulois broke his forks, the second of three Tours in which fork failure would snuff out any hope of victory for him, and a near half-hour advantage at the start of the day turned into a deficit of forty minutes. The peloton this time dawdled along at a sedate twenty-one kilometres an hour, taking more than twenty hours to complete the stage.

Romain Bellenger, who’d won the second stage, was first from a group of five. The main bunch arrived 4’02” down, Hector Tiberghien (Peugeot) taking the sprint for eighth, Bottecchia close behind Frantz’s wheel. He’d covered the wheel he needed to and survived the stage without a major mishap. The loser of the day was Legnano’s Brunero, who abandoned, saddle sores finally driving him off his bike, allowing Bottecchia’s Automoto team-mate Lucien Buysse to take the bottom step of the podium, almost an hour and a half behind Bottecchia. Brunero’s gamble to favour the Tour over the Giro had failed to pay off.

Londres’ description of the stage reads as follows:

Let’s start at the beginning. It was pouring rain and there was a howling wind; you wouldn’t put a guinea pig out on the balcony in such weather. The riders shuffled up, one by one, dragging their bikes, and they were given the off right into the teeth of the wind. Think what that would do to you: from midnight till four in the morning. The men pedalled through the night, chilled to the bone, in pouring rain. A sight to see. As soon as the sky began to lighten, the blackness slipped onto the men. I can tell you, these men who’d been white when they set off at midnight were black by four am. It’s true.”

From eating dust over the early stages of the race, the peloton was now sucking on the spray of the mud thrown up by their wheels and the passing cars. The race was passing over the pavé of the north of France, riders seeking the comfort of the pavement to ease their passage. The towns they passed through – Sedan, Lille, Armentières – were well known to most everyone in France in those days, they had been indelibly inked in their minds. Signposts marked the distance to Ypres:

In short, it took us back some years to our youth. Yet this was no war we were engaged in; it was a race. Judging from appearances there was no very great difference in the faces of those taking part.”

Londres’ reports from the 1924 Tour de France close with the journalist pressing home the central theme of his reportage, the suffering endured by these men in the name of sport and the hope of an income:

Sixty-one are going to make it. You can come and see them – these are no faint hearts. For a month they have fought with the road. The battles have taken place in the middle of the night, the early hours of the morning, though midday, groping their way through fog so thick it makes you retch, into headwinds which laid them flat, under the sun which, as in Crau, spit-roasted them on the handlebars. They have taken the Pyrénées and the Alps by the throat. They’d climbed into the saddle at ten o’clock one evening and not climbed off till the following evening at six – between Les Sables d’Olonne and Bayonne, for instance. They used roads not intended for bicycles. People barred their way. They’ve had level-crossing gates shut in their face. Cows, sheep, dogs have run into them. Yet, this was not the great torture. The great torture started from the moment they left and will last till they ride into Paris.

And there were the cars. For thirty days, these cars have driven alongside the riders and planed a layer off the road surface. They’ve planed it uphill, they’ve planed it downhill and thrown up a copious waste of dust without a word of complaint. Eyes burning, mouth parched, the riders have suffered the dust without a word of complaint. They’ve ridden over flint. They’ve devoured the coarse pavé of the north. When it was too cold at night, they’ve wrapped up their stomachs with old newspapers; by day, they’ve tipped pitchers of water over themselves, fully clad, and gone on watering the road until the sun had dried their jerseys out.

When they split open a leg or an arm in a fall, they climbed back on the machine. At the next village, they searched out the pharmacist. It might be a Sunday, as at Péznas, where the pharmacist told the injured man: ‘I’m closed for business.’ And, instead of shaking him by the neck till his teeth rattled, the rider replied: ‘Okay, sir’ and carried on riding.”

This, for me, is what is so special about the reports Albert Londres filed from the 1924 Tour de France: they concentrate on the human story, the inhumanity of cycle sport as it existed in those days.

The stage itself was a formality for Bottecchia: in those days it was still possible to lose the race on the last day, the riders had yet to get around to declaring the final day’s racing neutralised. But Bottecchia’s lead was more than sufficient for anything but the most dire of emergencies. In winning he became the first Italian to take the victory and the first rider to wear the maillot jaune from the first stage to the last (before 1919, when the maillot jaune was introduced, several riders led from the first day to the last: Bottecchia was the first to do it while wearing the yellow jumper).

Bottecchia put a ribbon on his overall victory by winning the bunch gallop on the track of the Parc des Prince, his fourth stage win in the Tour, adding another three minutes in bonifications to his lead over Frantz and Buysse. Of the sixty-one riders Londres thought were home and dry, spare a thought for Giovanni Canova, one of the touristes routiers. With Paris all but in sight, he failed to finish the stage.

And so ended the 1924 Tour, a race dogged by a doping controversy, a race that was won on the first day in the mountains. Some things don’t change down through the years.

Next: We skip forward in time to consider what became of Bottecchia, Pélissier and Londres.

* * * * *

Sources (throughout this part of the series): for most of the day-by-day racing, Bill and Carol McGann’s The Story of the Tour de France, Volume 1 (McGann Publishing). Some of the Londres translations are taken from Graham Fife’s Inside the Peloton (Mainstream Publishing). Les Woodland’s The Unknown Tour de France is one of the many that repeats the Jules Banino incident.

1 Comment

[…] Into the Alps and on to Paris. Tags: 1924, Albert Londres, Alphone Bauge, Jules Banino, Ottavio Bottecchia, Tour de France […]