With the 1924 Tour de France behind us, let’s step forward in time once more to see what became of the three men whose names will forever be linked with that edition of the grande boucle: Ottavio Bottecchia, Henri Pélissier and Albert Londres. We begin with the race winner, Ottavio Bottecchia.

Le Maçon de Frioul – the mason from Fruili –was born in the Veneto in 1894. The stories have it that Ottavio Bottecchia only discovered a passion for the bike during the first World War, when he was a member of one of the bicycle-mounted Bersagliere divisions, which rode to war on fold-up Bianchi bicycles. The Bersaglieri are frequently referred to as ‘the elite Bersagliere division,’ usually by authors who then go on to point out that, before taking up arms, Bottecchia had never ridden a bike before. Which makes you wonder just how elite the Bersaglieri were if they recruited men who didn’t even know how to ride a bike. Or how true the story of Bottecchia’s lack of pre-war cycling ability really is.

What is not in doubt however is that a number of the greats served with the Bersaglieri. Before Bottecchia there was Carlo Oriani, who won the 1912 Giro, at which time he was serving with the Bersaglieri in the Libyan conflict. Giovanni Brunero – Bottecchia’s Legnano rival in the 1924 Tour – also served his time in one of the bicycle-mounted regiments before going on to win three Giri. And after Bottecchia came Learco Guerra, another former Bersagliere, who rode his first Giro in 1929, was so unlucky in the 1930 Tour and finally won the Giro in 1934.

After Bottecchia had achieved fame in France, he described some of his war experiences:

[I remember] a long ride in the mountains, with a machine gun on my back, which I was to take to a lookout post that was under heavy fire. I had to ride on paths and tracks that were steeper than the Galibier or the Izoard. I arrived at my destination later in the evening after a risky Alpine climb. The next day I found out that my efforts had not been in vain. The Austrians attacked in the night and had failed to take the post thanks to the new machine gun.”

Bottecchia was a runner, ferrying messages and supplies between the trenches and firing positions at the front and the supply and command zones at the rear. Sometimes he himself got to use the machine gun he was ferrying, receiving a medal for his action in November 1917. The official citation states that:

calmly and bravely under violent enemy fire he returned fire efficiently and in a deadly manner with his own machine gun, inflicting serious damage on the enemy and stopping their advance. Forced on numerous occasions to retreat, he ignored the danger and carried his weapons with him so that he was able to open fire again and again.”

When the war ended Bottecchia moved to France and got a job working construction. There he put to work the cycling skills he’d learned in the army and took up bike racing, his winnings augmenting his income as be began to lay the foundations of family life. It turned out that he was pretty good at this cycling lark.

In 1923 Bottecchia, already 29, entered the Giro as one of the isolati, an unsponsored independent, isolated compared to those riders with team support, left to fend for himself. He finished the race just forty-five minutes behind the winner, Costante Girardengo (Maino): he was first in the isolati class and fifth overall.

Alphonse Baugé, the Automoto head-man – the Marshal mocked by Londres during the 1924 Tour –was impressed by Bottecchia’s Giro ride and offered the Italian a spot on the French Automoto Tour squad. Automoto were making moves on the Italian market, opening a showroom in Milan, and wanted a decent Italian rider on their squad so they’d get some column inches in the Italian press. Girardengo had reportedly turned them down when they came knocking on his door. Bottecchia was more than happy to take up their offer. Officially he was to be a gregario for Henri Pélissier. In the end he proved to be more than just another domestique, winning a stage, twice donning the maillot jaune himself – a first for Italy – and finishing second overall to Pélissier. The Alps proved to be Bottecchia’s downfall, the Italian having a mare of a day. The following year, as we’ve seen, he put those demons to rest.

During the 1924 Tour Le Gazzetta ran an appeal to raise funds for their new hero, even though he had shunned the Giro. Mussolini showed his support, contributing a symbolic lira. Il Duce was full of symbolics. The Italian public in general were a lot more generous than their dear leader, raising more than 60,000 lire for their new campione. That, added to his salary and bonuses from Automoto and the money won at the Tour (10,000 francs for winning, plus whatever his four stage wins earned him), meant that Bottecchia was, if not wealthy, then certainly armed with the foundations for a comfortable life.

That same year Bottecchia was also approached by Teodoro Carnielli, who wanted to produce bicycles bearing the champion’s name. Carnielli had a workshop in Vittorio Veneto and a few years earlier had come across Bottecchia, competing on poorly made bikes, the best he could afford at the time. Carnielli gave him a bike from his shop, a Ganna. With Bottecchia himself now a man of the Tour Carnielli suggested he do as Luigi Ganna and others had done before him and out his name on a range of bicycles. An astute businessman, Carnielli saw the profit potential in Bottecchia’s name and Bottecchia certainly appreciated the royalty that was being offered on every bike sold. He signed on the dotted line.

Bottecchia added to his wealth at the 1925 Tour, again winning four stages (including, again, the first and last stages) and again coming out on top. While the Tour’s overall prize fund fell marginally, the prize for winning was increased to 15,000 francs. The following year, though, Bottecchia was unable to make it three on the trot. The myths have it that he was defeated by bad luck (multiple punctures on the first stage), inclement weather and the very mountains he had soared over so effortlessly for the previous two years. Pre-echoing the myth of René Vietto, on the day he abandoned he is said to have sat on a wall and cried, telling journalists that it was all over: “I have had enough of the Tour. This is the last time. You need to think too much.” He was right: it was his last Tour.

In June 1927, just weeks before the commencement of what would have been his fourth Tour, Bottecchia was found mortally wounded on a road near his home in Fruili. He had been out for a training spin. Twelve days later he died in hospital of his wounds. For the past eighty-five years people have been arguing over how those wounds were inflicted. No one wants to believe that a great champion simply fell from his bike during a training ride and so the question of how inevitably leads to that of who it was who inflicted the wounds that killed Bottecchia. From there it’s but a short hop skip and jump to the why of it all. Money, sex, politics, they’ve all entered the mix. John Foot, in his Pedalare! Pedalare!, argues that this “tells us a lot about contemporary Italy, a country where the justice system is not seen as legitimate by many, and where disputes over the facts of the past, over history and memory, can drag on for years.” It also tells you a lot about our basic inability to accept that, sometimes, shit happens.

Although Bottecchia only ever rode one Giro, bikes bearing his name won in 1957 (Gastone Nencini), 1966 (Gianni Motta) and 1979 (Giuseppe Saronni). They also bagged a Tour de France, when Greg LeMond beat Laurent Fignon by that teeny tiny margin in 1989. The man who, it is claimed, was Christened Ottavio by virtue of the fact that he was the eighth child born to his parents (ottavo is Italian for eighth) lived again in the legend of a Tour won by just eight seconds.

* * * * *

A decade after Bottecchia’s death, they buried Henri Pélissier.

Pélissier’s full palmarès includes not just that sole Tour victory in 1923, but also three Giri di Lombardia (1911, 1913 and 1920), Milan-Sanremo (1912), Bordeaux-Paris (1919), two editions of Paris-Roubaix (1919 and 1921), and Paris-Tours (1922). Looking at any rider whose career spanned years of war, you always wonder what he could have achieved had he had an uninterrupted run at the sport. There’s more than enough coulda, woulda, shoulda stories in this sport though. If you are going to wonder, remember the obvious: many cyclists were killed in the Great War.

The Luxembourgher François Faber (who won the Tour in 1909) enlisted in the French Foreign Legion to do his bit in the war and was carrying a wounded comrade at Clarency in May 1915 when he was killed. Lucien Petit-Breton (who won the Tour in 1907 and 1908) was serving on the font lines June 1917 when he was killed in an automobile accident. Octave Lapize (who won the Tour in 1910) became an airman when the war commenced and he was killed in Combat over Verdun, also in June 1917. Many, many other professional cyclists were killed during the war, men like Henri Alavoine, Edouard Watteleir or Emile Engel, men who had achieved minor fame on the bike before the war. And then there was Carlo Oriani, a winner of the Giro d’Italia and a Bersagliere during the Libyan conflict. He contracted pneumonia when swimming across the river Piave during the retreat of Capoletto in November 1917 and died shortly after.

No one knows what races those who died might have been won, what champions they might have become, had war not cut their lives short. If you’re going to play coulda, woulda, shoulda, play it with them, not with the lucky ones who lived to race on.

During the 1924 Tour we’ve just looked at how Pélissier joked to Albert Londres that, one day, the riders would be made carry lead weights in their pockets, because someone would declare God had made them too light. That sort of thinking wasn’t far off the mark when it came to some of Henri Desgrange’s more wacky ideas. In 1925 he hit upon a brilliant new wheeze: no rider would be allowed eat more than another, all would receive the same food.

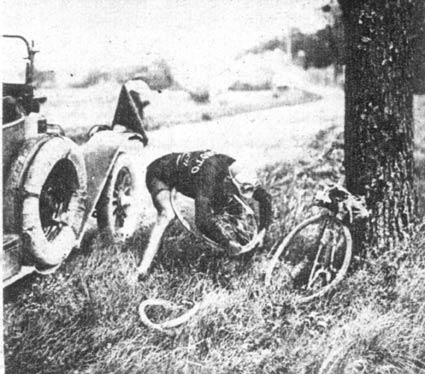

Pélissier changing his own tire during the Tour (photo courtesy the National Union of Professional Cyclists, uncp.net)

Pélissier had by this stage attempted to organise his fellow pros, forming a riders’ union, a forerunner of sorts to today’s CPA. On this issue – food – Pélissier had the support of the other riders and Desgrange was faced with the prospect of a riders’ strike. And a real one too, not the faux boycott faced by the organisers of the 1924 Giro d’Italia. On mature reflection Desgrange decided not to press ahead after all with his food idea. Victory for the riders.

But just about the only victory for Pélissier’s union. Few riders could be bothered siding with him on other issues. The Belgians saw no reason to join his crusade: they were profiting from a sport which rewarded cart-horses. As for Pélissier’s compatriots, few of them needed the trouble that being visibly aligned with Pélissier would bring them. Trouble with men like Alphonse Baugé and Henri Desgrange. The union died.

Pélissier died in 1937, shot by his mistress, Camille Tharault, during a domestic dispute. He’d pulled a knife and she’d reached for a gun. The same gun which, two years earlier, had been used by Pélissier’s wife, Léonie, when she committed suicide. It was a clear a case of self-defence, if somewhat excessive: Tharault had put five bullets into Pélissier. He was forty-six years old.

If you were to cast about for a contemporary equivalent of Pélissier someone like Roy Keane would perhaps be a good analogue. Pélissier was a talented athlete with his own views on the way things should be done and unable – or unwilling – to compromise when it came to expressing his opinion. After he’d retired – a decade before his death – Pélissier tried a comeback of sorts, as a manager, but that didn’t last long. The best athletes rarely make good managers, they don’t understand how others struggle to reach the heights they scaled so effortlessly. So Pélissier then tried his hand at punditry. Well you can guess how that worked out, can’t you?

A journalist, Alber Baker d’Issy – creator of the GP des Nations – wrote an obituary for Pélissier which probably got the man just about right:

He had few friendships because of his absolute opinions, and the way he expressed them cost him many friends. […] But they all bowed to the great quality of a champion they considered the greatest French rider since the war.”

It probably would have killed Desgrange to admit it but Pélissier’s criticism of the Tour was right. The stages were too long. Desgrange himself had to acknowledge this, not because he finally began to empathise with the riders, but because the super-long stages became ever more boring. Riders would simply ride together until close to the finish when the real racing would begin. Desgrange’s attempts to enliven the stages with bonifications ultimately failed. At one point he even resorted to setting the riders off in time-trial fashion in an attempt to make them race the whole stage long. Soon he had no choice but to accept reality. In 1927 the Tour was redrawn: twenty-four stages with only seven rest days but with stage lengths reduced. Stages ranged in length from 103 kilometres to 360, ten of them were below 200 kilometres. The conditions the riders toiled in were still primitive but the Tour’s parcours had entered the modern era. The cart-horses were being consigned to history and the Tour was becoming a race for Thoroughbreds.

* * * * *

Had Albert Londres lived long enough, perhaps he would have written a fine obituary for Henri Pélissier, championed him for standing up to Henri Desgrange and trying to bring some humanity to the sport of bicycle racing. Londres, alas, was himself five years dead by the time Pélissier was buried.

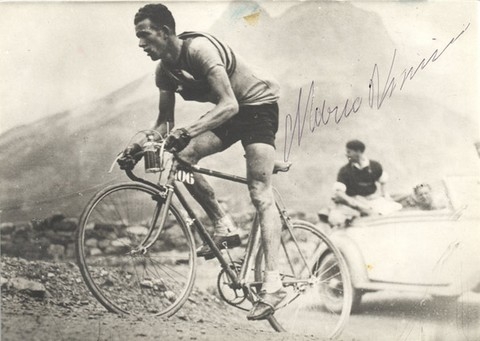

The last-known picture of Albert Londres, in Shanghai in 1932 (source: Assouline’s monograph, “Albert Londres”)

In the years after 1924 Londres had reported from Senegal and the Congo, where he raged against colonialism and condemned the manner in which slavery was being used there. Then it was on Palestine to report on the attempt by Jews to establish a Jewish state. His last completed report came from the Balkans, where he covered Macedonian nationalists who had turned to terrorism in protest at the division of their land between Greece, Bulgaria and Serbia. Londres’ final assignment was in China, where he was investigating attempts by the Bolsheviks to stir up unrest. It was while he was returning from China that Londres died, when the ocean liner on which he was sailing caught fire and sank.

In the eight years between his reports from the 1924 Tour de France and his death in 1932 Albert Londres never again reported on the grande boucle. I guess there was always some greater injustice out there needing to be written about, no time to circle back and revisit stories already told once. But the fact that Londres did cover the Tour, even the once, is some indication of how important the race had become just twenty-one years after its creation. And how cruel and unfair cycling as a sport was then. Nothing like the sport we know today. Nothing at all like the sport we know today. Right.

Next: When we resume, we’ll look at the Giro di Lombardia and some other races from the 1924 cycling season.

No Comments