Twenty five years ago this year, Irish cycling was on top of the world. We had a World Champion. We had the winner of the Tour de France. We had the winner of the Giro d’Italia. We’d come within a cat’s whisker of winning the Vuelta d’España. Irish cycling rocked like it had never rocked before. Oh, we’d had a World Champion before, away back in 1896 when Harry Reynolds won the amateur sprint title. But in the Grand Tours … before 1987, there was nothing, save a podium place, some stage wins, a few days in yellow, and a few green jerseys. No, in the Grand Tours, before 1987, Ireland hadn’t hit the high notes. Or had we?

Cycling’s official history is skewed toward Europe, largely because the Tour de France acts as a distorting mirror. Slowly, the distorting effect of the Tour is being reduced and we’re learning to appreciate the rich history of other races. Slowly, revisionism is taking root and the history we thought we knew is being rewritten, cast in a different light, to reveal a richer, deeper picture. Slowly, we are taking the time to reconsider forgotten corners of cycling’s past.

Matt Rendell’s Colombian trilogy has helped us appreciate that country’s cycling heritage. Andrew Homan’s current project, a biography of Reggie McNamara, will help shine a new light on the early history of Australian cycling, as well as cycling in America and Europe. Herbie Sykes is soon set to try and encourage us to re-evaluate our perception of the Peace Race, that Communist-era tour that originally connected Czechoslovakia and Poland, by way of East Germany. And in time, I think, we will re-evaluate the way we consider the race that was, in my opinion, America’s Grand Tour: the Madison Square Garden International Six Day Race. And when we do that, we’ll find that 91 years before Stephen Roche won a first Grand Tour victory for Ireland, an Irishman won America’s Grand Tour.

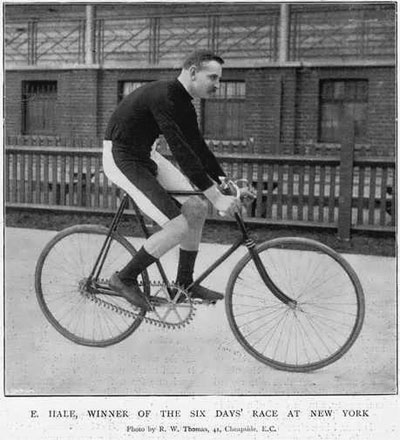

That man was Edward ‘Teddy’ Hale. Most Irish cycling fans can give you chapter and verse on Sean Kelly and Stephen Roche. We can rattle off all the Irish riders who have participated in the Tour. We know the basic outline of Shay Elliott’s career. We can even tell you something about Harry Reynolds: the Balbriggan flyer, Ireland’s first World Champion, the man who refused to step up on the podium at the World’s as long as the band were playing the British national anthem. But few in Ireland have ever even heard of Teddy Hale, the man who won in the Garden in the same year that Reynolds was crowned World Champion.

One of the simplest reasons for this is that the race Hale won has ceased to exist. Like many races today, the Garden Six simply fell out of fashion, couldn’t finance itself and passed quietly into the dusty pages of history. Without current riders to consider its winners against, we more or less forgot about the Madison Square Garden International Six Day Race. Consigned it to a corner of cycling history marked ‘nostalgia.’ But there really is a lot more to the Garden Sixes than mere nostalgia for a bye-gone age.

A newspaper portrait of Edward ‘Teddy’ Hale: “Winner of the Six Days Race, Champion of Ireland and Long Distance Champion of the World.” Source: Sporting Life

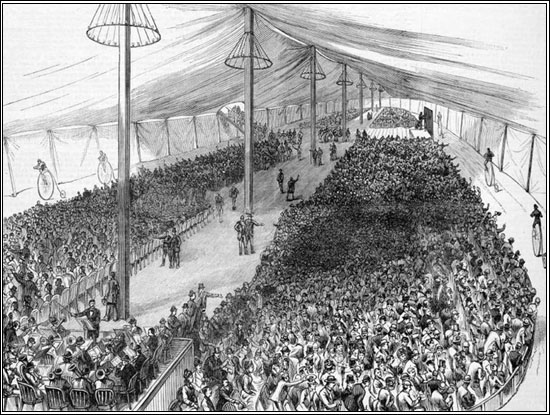

The early history of Six Day racing – being so long ago and so rarely excavated – isn’t always easy to tell, not without repeating mistakes. But that’s not stopped the dozens – hundreds? – of Tour histories that repeat the same errors over and over again, so it shouldn’t stop the history of Sixes being retold, errors and all. What is known is that Six Day races seem to have started in the UK. The first appears to have been held in Birmingham, in 1875, the riders putting in twelve hours a day, Monday through Saturday. The first Six Day race without scheduled stops seems to have happened in London, in Islington’s Agricultural Hall, in 1878. Which is the first ‘real’ Six Day race – Birmingham or London – is hardly worth arguing over, unless you’re a Brummie.

A year after the Islington race, Boston had a Six, the riders riding ten hours a day. Over the next few years more and more Sixes began to be put on in the States – in Chicago, Detroit, Memphis, Milwaukee, Minneapolis, New York, Omaha, and St Paul. In each of those cities riders put in between three and fourteen hour days, Monday through Saturday. And the crowds flocked to see them ride.

The popularity of Sixes in the States in those days is evident not just from the number of cities that hosted them, but also from the fact that over the course of 1888 and 1889, at least five women-only Sixes were organised; when women get a chance to race, and can pull in paying punters to watch them race, you know the sport is doing well. But the women weren’t just racing against one another: Louise Armaindo raced against – and beat – men in Sixes, forty years before Alfonsina Strada took part in the 1924 Giro d’Italia.

The popularity of Six Day racing was particularly evident in 1887 when Tom Eck, a former pro from England who was making a name for himself as a promoter in the States, put on what is believed to be the first American Six that didn’t have scheduled breaks, in Minneapolis. Then, in 1891, Eck took his grand idea to Madison Square Garden in New York City. Riding on a high-wheeler, and circuiting a flat track, ‘Plugger’ Bill Martin knocked off 2,360 kilometres in the 142 hours of racing between midnight on the Sunday night / Monday morning and ten o’clock on the Saturday evening.

For most of the next half century, New York was where the American cycling season reached its zenith and where, for a brief period in the twenties and thirties, the Garden Sixes were so popular that the promoters were organising two a year, Spring and Winter, bookending the American cycling season the same way Milan-Sanremo and the Giro di Lombardia bookend the real European cycling season.

Three views of the exterior of Madison Square Garden in the early 1900s. Source: Library of Congress

Before getting into the 1896 Garden Six itself, it’s worth taking a moment to consider what the world was like back then. America was coming out of a depression caused by the bursting of the railways stock bubble a few years earlier. Utah had only recently become the 45th state in the Union. McKinley was waiting in the wings, ready for his inauguration as Cleveland served out his last days in the White House. Only in three states had women been allowed vote in the presidential election and California had just refused to extend the franchise beyond men.

Across the Atlantic, Salisbury ruled from Downing Street, Victoria was on the throne, Kaiser Wilhelm ruled the German Empire. France was in its Third Republic and the Ottoman Empire had not yet collapsed. Competing imperial powers were carving up Africa among themselves. Puccini’s La Bohème, Wilde’s Salomé and Jarry’s Ubu Roi were among the cultural high-points of the year. Bram Stoker was putting the finishing touches to Dracula, which would be published the following year. Moving pictures were in their infancy. In England was born the Daily Mail, in Italy La Gazzetta dello Sport. The Olympics had just been revived.

What was happening in cycling? In May Bordeaux-Paris was won by Arthur Linton and Gaston Rivière, the Welsh rider first home but the French rider given a share of the podium after a dispute over the route Linton had taken when crossing the Seine (six weeks later Linton would be dead, a death commonly associated with doping but actually the result of typhus). Rivière also won the Bol d’Or. Milan-Turin went to Giovanni Moro while Paris-Roubaix went to Josef Fischer. Lucien Eugène Prévost pocketed Paris-Tours. At the Worlds in August Harry Reynolds won the amateur sprint title for Ireland. Those are the main races remembered today but the calendar – both road and track – had a lot more colour to it than just those few races suggest.

Thirty-one riders were listed to start the 1896 Garden Six, 17 of them from the US, the rest drawn from Canada, Denmark, England, France, Germany, Ireland, Scotland and Wales. England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales between them were fielding seven riders: you have to remember here that, at the end of the nineteenth century, the British were bloody good at cycling, on both the road and the track, they hadn’t yet entered their shy and retiring phase.

The Garden Sixes traditionally had curtain-raising events on the Saturday, with spectators crowding into the arena on the Sunday evening being entertained by the band of the Sixty-Ninth Regiment until the actual racing began a little after midnight. The 1896 Saturday night curtain raisers consisted of amateur and professional short distance races in front of a crowd of about 5,000 people. Some of the riders due to take part in the Six itself also took part in these races.

The half mile handicap saw the professional debut of Marshall ‘Major’ Taylor, who’d been making a name for himself on the amateur circuit over the previous couple of years. The neo-pro opened his new career with a victory over Eddie ‘Cannon’ Bald, then the best short distance rider in the United States. And then he took the line for the Six itself.

The 1896 Madison Square Garden International Six Day Race was got underway at six minutes after midnight, by Albert Zimmerman, the first great American cyclist (and possibly America’s first international sporting star). The first day’s racing was livened up by a prize of $50 for the rider who rode the furthest without dismounting, the money being put up by a former rider, ‘Senator’ Morgan, who’d set a record of 380 kilometres in London some years previous. Ned Reading, a thirty-three-year-old soldier from Omaha, Nebraska (by way of Ohio), eased past Morgan’s record and pushed the distance out to 394 kilometres without once getting off, having declared before the start his intention to tackle Morgan’s record.

Reading was on a leave-of-absence from his army posting to Forth Keogh, Montana, where he was a member of the United States infantry band. For a soldier who was on $13 a month, the $50 he won for bettering Morgan’s record was a welcome reward. As well as being a member of the infantry band Reading was an accomplished Six Day rider: out of twenty-two Sixes he’d started so far in his cycling career he’d won fourteen, including Chicago in 1889 and Omaha in 1891. Three years earlier, in 1893, he’d finished fourth in the Garden Six. His early show of strength must have bode well for the rest of the week’s racing.

The first day also saw the separating of the wheat from the chaff, with many riders falling by the wayside inside the first twenty-four hours. One of the American riders, Cartwright, crashed just two hours into the race, putting a gash into his leg which put him out of the race. One of German riders, Waller, collided with an American rider, Van Emburgh, whose chain had broken, and both were forced to retire hurt, Waller with a broken nose and cheekbone. Eddy Merckx or Bernard Hinault might have ridden on regardless, but not Waller.

Tom Linton – brother of Arthur, protégé of Choppy Warburton and a rising star of British cycling – abandoned early and spent the rest of the week participating in the short exhibition races which filled the card in the afternoons and evenings, along with (during the week Linton would set a new unpaced five mile record, 12’04.8″). The third Linton brother, Sam, was also signed for the exhibition events which supported the Six.

The surprise of the first day was probably Albert Shock, a veteran of 30 Sixes and the defending champion in the Garden (he’d also won the race in 1893, when it was still being contested on high-wheelers). At the end of 24 hours he was already more then 90 kilometres off the pace, languishing down in seventh place. His trainer, Billy Young, was putting on a brave face, promising reporters that Schock would be in the hunt by the close of the week.

The star of the day, though, was the man out-pacing all his rivals: Teddy Hale. He took the lead at about eight o’clock and thereafter put more and more distance between himself and his rivals. As well as Rice toppling Morgan’s record, the record for distance covered in the first twenty-four hours – 648 kilometres – fell with Moore, the Quaker, putting in 657 kilometres. But ahead of him was Hale, piling on 686 kilometres in the first day. Reading was just below the record, 43 kilometres off Hale’s pace, with Taylor 19 kilometres further back.

Only the sketchiest information is known about Teddy Hale: he’s reported to have been born on May 30, 1864, in Templepatrick, just north of Belfast. This put him at 32 years of age by the time he took part in the 1896 Garden Six. Standing five foot ten and a half inches tall (1.79 metres), he weighed in at 161 pounds (73 kilograms). Tall and lean would seem to be a fair description of him.

Hale’s riding career is said to have begun in 1885, on a high wheeler, when he was 21. That year he was reported to have won “the Kangaroo event of 100 miles,” with a time of six hours and 59 minutes. The following year, it’s said, he won the Championship of Europe, covering a tad over 10 kilometres in just over eighteen minutes.

Hale seems to have specialised in distance events and claimed to have been the first man to crack five hours for a century. Coming into the Garden Six he was the reigning British champion at 100 miles (Ireland, back then, was part of Britain, independence was still a quarter of a century and a lot of bloodshed into the future). In all he reckoned he’d already won more than 500 prizes by the time he appeared at the 1896 Garden Six. A lot of those races seem to have been British races and among the events he claimed to have won was the North Road 100 mile race, which he clamed to have won nine times straight. He was also reported to have won the John O’Groats to Land’s End race, a distance of more than 1,400 kilometres, “two or three times.”

Some sources say Hale won a race from Paris to Bordeaux. Other sources say he won a race from Paris to Rouen. Nether of these two victories can be found on Memoire du Cyclisme so it is entirely possible that Hale’s palmarès was being boosted: Bordeaux-Paris was in the news, having been won by Arthur Linton, and Paris-Rouen is generally recognised as the first proper place-to-place road race.

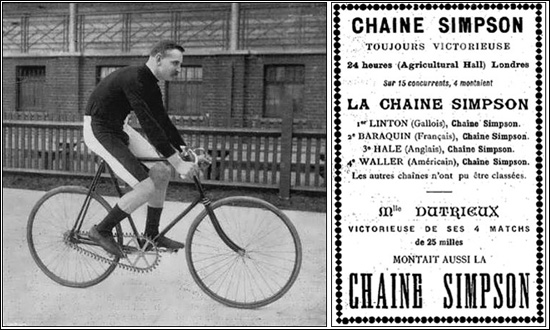

Hale’s only previous outing in a Six was in a London race, where the riders only had to be in the saddle for fours hours a day, bringing them to a total of 24 hours raced over the course of the week. That British Six was probably the March 23-28 race held in the Agricultural Hall, Islington, London. Arthur Linton – his Bordeaux-Paris victory still in the future – won the race, with 791 kilometres, with a French rider, Gabriel Baraquin, less that a metre behind him. Hale was home in third, with 790 kilometres. As well as Hale at least one other rider at the 1896 Garden Six also participated in that Islington meet, Frank Waller, who finished fourth, a few metres behind Hale.

The Agricultural Hall is, as already noted, one of Six Day racing’s ground zeroes, depending on which version of the discipline’s official history you go by. Islington’s Sixes were popular affairs, with five to six thousand punters filling out the Agricultural Hall for the final evening’s racing in 1896, which is not far off the capacity of the London 2012 vélodrome. On the undercard throughout the week had been shorter races, including women’s events. Dutrieux (France) beat Howard (England) in a series of 25 mile races, and – teamed up with Eteogella – defeated the British pair of Howard and Grace in a series of shorter races. Other women competed in sprint races during the week.

Photograph of Edward ‘Teddy’ Hale and Chaine Simpson advertisement marking the success of their riders in the 1896 Islington Six. As well as Linton, Baraquin, Hale and Waller, Dutrieux was also racing using a Simpson chain. Source: SixDay.org.uk

Twenty-five hours into the race, at one o’clock on the Tuesday morning, the 1896 Garden Six was shaping up like this:

| 1896 Madison Square Garden International Six Day Race Position at One AM, Tuesday, December 8 (25 hours in – 117 hours to go) | ||||

| Name | Representing | Nationality | Kilometres | |

| 1 | Edward ‘Teddy’ Hale | Ireland | 697.3 | |

| 2 | EC Moore | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania | America | 657.3 |

| 3 | Edward ‘Ned’ ‘Soldier Boy’ Reading | Omaha, Nebraska | America | 654.8 |

| 4 | Marshall ‘Major’ Taylor | South Brooklyn | America | 640.8 |

| 5 | Albert Schock | New York | America | 615.7 |

| 6 | CW Ashinger | Upshur | America | 614.9 |

| 7 | JS ‘Joe’ Rice | Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania | America | 613.8 |

| 8 | Burns W Pierce | Boston | Canada | 607.2 |

| 9 | Fred Forster | New York | Germany | 589.8 |

| 10 | WA Elkes | England | 577.6 | |

| 11 | JA Glick | Detroit, Michigan | America | 571.8 |

| 12 | EC Smith | Saratoga | America | 565.0 |

| 13 | JW Conklin | America | 557.2 | |

| 14 | HH Maddox | Asbury Park, New Jersey | America | 528.8 |

| 15 | JR Gannon | New York | America | 519.2 |

| 16 | SL Cassidy | Millville, New Jersey | America | 516.6 |

| 17 | Ed van Steeg | Germany | 508.1 | |

| 18 | Peter ‘Stayer’ Golden | America | 482.2 | |

| 19 | DM McLeod | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania | America | 461.9 |

| C Chapple | England | Retired | ||

| William Lumsden | Scotland | Retired | ||

| Tom Linton | Wales | Retired | ||

| George Cartwright | England | Retired | ||

| George ‘Boy Wonder’ van Emburgh | America | Retired | ||

| Frank ‘Flying Dutchman’ Waller | Germany | Retired | ||

| Jules Dubois | France | ?Retired | ||

| EJ Flynn | America | ?Retired | ||

| AA Hansen | Denmark | ?Retired | ||

| Albert Hosmer | America | ?Retired | ||

| AC Meixel | America | ?Retired | ||

| J Wilson | England | ?Retired | ||

| Source: Sporting Life | ||||

Over the next 24 hours the field was whittled down further, with just 16 riders left in the race come one o’clock on Wednesday morning. If that makes you think the field assembled for the race wasn’t all that impressive then consider the attrition rate in the early Tours and Giri: they too had their fields padded with cannon fodder, with the withdrawals early in the race quickly whittling the field down.

In assembling a field for a Six Day race promoters had to balance different objectives. For a start, there was a limit on how much they could shell out to attract international riders: the books hadto balance, with that balance requiring quite a healthy surplus for the promoters’ pockets. And all the revenue had to be earned: there were no state subsidies for cycling back then, unlike today.

The way the field was assembled – participation was by invite only – was not unlike the way a critérium is organised today: there the promoter typically invites a handful of genuine stars, a handful of local stars and simply pads the rest of field out with inexpensive cannon fodder. So yes, maybe some of the riders in the 1896 Garden Six weren’t quite up to international standard, weren’t going to make the race competitive. But then how many races are there where the whole field is bent on victory?

By one o’clock on the Tuesday morning – two days into the six – Hale was still leading, having added another 545 kilometres to his tally to bring him up to 1,242 kilometres. He was also still ahead of the record: Schock had preciously ridden 1,180 kilometres for the first 48 hours, Hale had pushed that out to 1,239 kilometres. Having never competed in a continuous Six Hale was an unknown quantity for the fans and, while he was beating early records, no one could tell how well he would perform as the week wearied him and wore him down. How serious Hale was taking the race some fans questioned, when they saw him was seen smoking a cigarette.

Schock had by now dragged himself back into the race, still nearly 80 kilometres off Hale’s pace but now third overall and looking strong. The star of the second day was Rice, who piled on 613 kilometres, pulling himself up to within 15 kilometres of the Irishman. In a Six, that was no distance at all. The race was shaping up to be a competitive one.

Rice was a 26-year-old Russian Pole who had lived in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, since he was five years old. His reason for putting in for an invite to the Garden Six was that he was the proprietor of a bike shop in Wilkes-Barre and was looking to pull off an exploit as a means of promoting himself and his mechanical abilities: the bikes he rode he’d built himself. To be able to go back to Wilkes-Barre with a name made in Madison Square Garden would surely help drum up business. He’d previously started a Six, in 1892, but abandoned. Apart from that, he was an unknown quantity.

| 1896 Madison Square Garden International Six Day Race Position at One AM, Wednesday, December 9 (49 hours in – 93 hours to go) | ||||

| Name | Nationality | Kilometres Added | Total Kilometres | |

| 1 | Hale | Ireland | +545.1 | 1,242.4 |

| 2 | Rice | America | +613.3 | 1,227.1 |

| 3 | Schock | Germany | +549.6 | 1,165.3 |

| 4 | Reading | America | +498.9 | 1,153.7 |

| 5 | Smith | America | +574.4 | 1,139.4 |

| 6 | Forster | Germany | +538.5 | 1,128.3 |

| 7 | Pierce | Canada | +506.1 | 1,113.3 |

| 8 | Moore | America | +450.9 | 1,108.2 |

| 9 | Taylor | America | +460.3 | 1,101.1 |

| 10 | Ashinger | America | +418.9 | 1,033.8 |

| 11 | Maddox | America | +494.4 | 1,032.2 |

| 12 | Cassidy | America | +448.7 | 965.3 |

| 13 | Glick | America | +392.4 | 964.0 |

| 14 | Elkes | England | +383.0 | 960.6 |

| 15 | Gannon | America | +380.4 | 899.6 |

| 16 | McLeod | Scotland | +308.7 | 770.6 |

| Conklin | America | Retired | ||

| Golden | America | Retired | ||

| Von Steeg | Germany | Retired | ||

| Source: Sporting Life | ||||

Fans trying to follow the racing had the help of a scoring system that mixed the modern with the ancient. The Madison Square Garden track measure ten laps to the mile. Poles with 10 electric lights on them had been erected and, each time a rider completed a lap, one of the lights on his pole came on. When all the lights on the pole were lit a chalk scoreboard was updated and the lights reset to count off the next mile.

That eased some of the confusion, but didn’t eliminate all of it. One of the difficulties in following single-rider Sixes was knowing which riders had stopped and which riders were due to stop. Riders could get off their bikes whenever they wanted, for as long as they wanted. But, while they were off their bikes, their rivals could still be riding on, clawing back lost miles or stuffing more miles onto their lead. Riders had to have a good strategy for balancing their sleeping and their racing. And fans had to have the mental acuity of a chess grandmaster to keep up with how the individual riders were really faring.

Take Rice: it’s claimed that he got through 1,283 kilometres before he got some sleep, which brought him up to nearly four o’clock on the Wednesday morning, 52 hours into the race. Hale would claim at the end of the race to have slept no more than eight hours over the course of the six days of racing. Schock had taken two hours sleep in the first 48 hours, and intended riding through the next 24 without rest and then taking a three hour sleep break. Major Taylor, on the other hand, was taking an hour’s sleep for every eight hours he rode.

It was only as the race wore on that fans could get a clear picture of the relative merits of the different riders. Which, I guess, is not unlike what happens in stage races on the road. By Wednesday morning, the picture of what was really going on at the 1896 Garden Six began to become clearer:

| 1896 Madison Square Garden International Six Day Race Position at One AM, Thursday, December 10 (73 hours in – 69 hours to go) | ||||

| Name | Nationality | Kilometres Added | Total Kilometres | |

| 1 | Hale | Ireland | +482.6 | 1,725.1 |

| 2 | Rice | America | +459.5 | 1,686.6 |

| 3 | Forster | Germany | +524.2 | 1,652.5 |

| 4 | Moore | America | +526.6 | 1,634.8 |

| 5 | Schock | Germany | +441.6 | 1,606.9 |

| 6 | Reading | America | +444.0 | 1,597.8 |

| 7 | Taylor | America | +486.7 | 1,587.8 |

| 8 | Pierce | Canada | +469.8 | 1,583.1 |

| 9 | Smith | America | +440.2 | 1,579.6 |

| 10 | Ashinger | America | +473.5 | 1,507.3 |

| 11 | Maddox | America | +440.8 | 1,464.0 |

| 12 | Cassidy | America | +433.2 | 1,398.5 |

| 13 | Glick | America | +390.9 | 1,354.9 |

| 14 | Gannon | America | +375.9 | 1,275.6 |

| 15 | McLeod | Scotland | +342.3 | 1,112.0 |

| Elkes | England | Retired | ||

| Source: Sporting Life | ||||

By the time Thursday came around it was becoming clear that the old record for the distance covered in a Six Day race – 2,575 kilometres, set by Schock a few years previously – was likely to be surpassed. At this stage in cycling’s history speed records were falling with regularity, as technology improved, particularly drive-train technology. Hale, for instance, was using the Simpson chain, something quite different to the chains we know today. Chainless-drives using shaft-driven bevel gears were also becoming the rage: Gaston Rivière won Bordeaux-Paris on a chainless bike three times between 1896 and 1898. In later years both Hale and Taylor would actively promote chainless bicycles, Taylor setting a number of world records riding one. Having ridden a Simpson chain earlier in the season it’s likely that that was the transmission being used by Hale in New York. One note from the 1896 Garden Six mentions this about Hale’s bike, during the second day of the race:

Hale tried a new wrinkle on his wheel during the afternoon. It is called a forcipede. This is an adjustable attachment which gives the back a purchase and exerts additional driving power with the slightest amount of energy.”

But the increase in speeds at the 1896 Garden Six wasn’t just down to technology: a lot of it had to do with the quality of the field. With so many riders grouped so close the top riders were pushing one and other to stay out on the track longer and maintain – or better – their relative positions. Hale’s lead of 39 kilometres over Rice at 69 hours to go was the equivalent of two or three hours which, allowing for the time off to sleep, wasn’t an insurmountable gap. At that same time, the gap between fifth and ninth was little more than an extra hour or so on the track.

Rice’s second place was constantly being challenged. At one point of the fifth day Forster overtook him, only for the effort to catch up with him and cause him to ride erratically and crash a couple of times. Rice was also being pushed by Reading. The more Forster and Reading and the others pushed Rice, the more Hale had to respond in order to stay clear of the lad from Wilkes-Barre.

As the racing wore on the riding got slower and slower. Sixes could be deadly dull affairs at times with not an awful lot seeming to happen. Which is why, to keep the crowd cheering, promoters added exhibition events during the race, usually short distance sprints. Most of the time the riders stayed on the track while these were going on, circuiting high or low on the wooden oval to stay out of the way of the fresh legs waking the crowd up. Hale, though, used these events as an opportunity to leave the track, to feed at a table or to get his legs rubbed down.

As well as the exhibition events the crowd had the band in the infield to keep them entertained, the musicians changing their tunes to suit what was happening on the track. For Hale – clad in “as much green as can be stretched over his lanky frame” – the band played ‘Wearing of the Green.’ They changed their tune when Taylor came to the front:

But the tune changes to ‘Dixie’ in a jiffy as Major Taylor, the burned-to-a-crisp tamale from South Brooklyn, challenges the foreigner and picks him up for a sprint. And ‘Dixie’ it is for some time, for the black whirlwind sweeps past like a swallow on the wing.”

As the race entered its penultimate day, the picture looked like this:

| 1896 Madison Square Garden International Six Day Race Position at One AM, Friday, December 11 (97 hours in – 45 hours to go) | ||||

| Name | Nationality | Kilometres Added | Total Kilometres | |

| 1 | Hale | Ireland | +466.2 | 2,191.3 |

| 2 | Rice | America | +454.3 | 2,140.9 |

| 3 | Forster | Germany | +486.2 | 2,138.7 |

| 4 | Reading | America | +502.1 | 2,099.9 |

| 5 | Schock | Germany | +439.5 | 2,046.4 |

| 6 | Taylor | America | +443.7 | 2,031.5 |

| 7 | Smith | America | +442.4 | 2,022.0 |

| 8 | Moore | America | +367.4 | 2,002.2 |

| 9 | Pierce | Canada | +417.9 | 2,001.1 |

| 10 | Maddox | America | +455.0 | 1,919.0 |

| 11 | Ashinger | America | +399.8 | 1,907.1 |

| 12 | Cassidy | America | +424.9 | 1,823.4 |

| 13 | Gannon | America | +392.7 | 1,668.2 |

| 14 | Glick | America | +174.8 | 1,529.7 |

| 15 | McLeod | Scotland | +356.1 | 1,469.0 |

| Source: Sporting Life | ||||

Hale was by now carefully pacing himself against Rice, edging himself clearer of his challenger as the hours piled up. While Rice was still in with a fighting chance it was going to take a défaillance on Hale’s part to unseat him. Certainly Hale didn’t look like he was going to break down physically and run out of fuel. Consider his daily diet, which the New York Times detailed as being:

Four pounds of roast chicken, four quarts of beef tea, four quarts of chicken tea, one pound of boiled rice, one pound of oatmeal, two bowls of custard, fish every other day, milk toast, jelly and tapioca, and between two and three pounds of fruit.”

For the most part riders ate on the hoof, food being passed up to them in a tin can with a funnel on it: cotton musettesare for sissies. After two or three days of cramming food down your gullet to replace the calories raced off you, eating becomes a chore, which is why so much of Hale’s diet consisted of foods which easily slid down his throat.

But keeping up with the calories burned off was just a minor chore: the real hardship came from sleep deprivation. Aching muscles could be borne but the effects of staying awake too long were much harder to deal with. At the end of the race one newspaper report noted how the lack of sleep wore the riders down as the race went on:

In the over-powering fatigue they felt Hale and the others were seized with a kind of mania. Another day and the brains of some of them would have give way. Hale thought the other riders were trying to crowd him. The truth was that they knew Hale was a sure winner.

Rice, the American, had become a sullen and fearless lunatic early in the day [on Saturday]. His senses had gone astray as early as Wednesday and his lucid intervals had been intermittent ever since. At eight o’clock he dismounted his wheel on the south side of the course and crouched, trembling and cowering against his wheel.

Trainer and attendants rushed over and helped him to his feet. ‘Make ’em stop,’ he muttered, ‘they’re throwing brickbats and pebbles at me. I won’t go on if they ain’t made to stop it.’ He was drenched with water and rubbed a bit and consented to remount. Half a dozen times between then and the finish, however, Rice ran his machine to the rail, got off sulkily and refused to remount. ‘Take it away,’ he would mutter, hoarsely, when the bicycle was brought up for remounting, ‘I don’t want to see it again.’

‘Majah’ Taylor, the Brooklyn Ethiop, lost his primitive wits too, about eight o’clock. A racial instinct coloured the Majah’s fatigue-born phantasms. One of his attendants tried to hand him a bite of something on a tin plate during one of his breathing spells, and the little Congo athlete shied like a colt. ‘Drop dat knife’ he shouted, ‘they wants to kyarve me suah.'”

It’s at this point that we need to consider doping. In 1896 there were no rules against the use of questionable medicines in bike races; we had to wait another seven decades before anyone would get around to addressing that issue, even half-heartedly. Stimulants to keep you awake were part and parcel of the cycling game from its earliest years, as races became as much a test of the human body as the bikes the riders rode on.

Not all riders dabbled with dope, but enough did for track racing, in particular, to gain a reputation for doping. That reputation was aided by the fact that, with no prohibition against their use, many spoke openly about what was and wasn’t used. And then there were those who played a psychological game, keeping their secrets to themselves and leaving others to imagine what might be being passed up to rivals. As a way of getting inside a rival’s head and making him think he was beaten, having a trainer make a show of handing up a medicine bottle – contents unknown – was as good as any. Once in one road race Gino Bartali, having arrived at the stage finish, drove back down the route he’d just raced in order to retrieve a bottle thrown away by Fausto Coppi, in order to discover the secret of Coppi’s success, which Bartali was sure was related to doping. Nothing of any great consequence was discovered when the bottle’s contents were analysed. Cycling has always been about the head and the legs, and races that should have been won with the legs have been lost with the head.

Track cycling’s doping reputation presents a problem when you consider Sixes, especially these early ones. Many will automatically assume that doping was the cause of the riders’ wandering minds. But give a man just two or three hours sleep a day and ask him to ride around a vélodrome hour after hour, and you can produce the same effects without recourse to doping.

| 1896 Madison Square Garden International Six Day Race Position at One AM, Saturday, December 12 (121 hours in – 21 hours to go) | ||||

| Name | Nationality | Kilometres Added | Total Kilometres | |

| 1 | Hale | Ireland | +475.9 | 2,667.2 |

| 2 | Rice | America | +455.1 | 2,596.0 |

| 3 | Forster | Germany | +448.2 | 2,586.9 |

| 4 | Reading | America | +452.7 | 2,552.6 |

| 5 | Schock | Germany | +473.5 | 2,519.9 |

| 6 | Smith | America | +438.1 | 2,453.8 |

| 7 | Taylor | America | +421.6 | 2,453.1 |

| 8 | Moore | America | +412.8 | 2,415.0 |

| 9 | Pierce | Canada | +410.5 | 2,411.6 |

| 10 | Ashinger | America | +448.2 | 2,355.3 |

| 11 | Maddox | America | +406.2 | 2,352.2 |

| 12 | Cassidy | America | +392.0 | 2,215.4 |

| 13 | Gannon | America | +281.6 | 1,949.9 |

| 14 | McLeod | Scotland | +389.3 | 1,858.3 |

| 15 | Glick | America | +144.7 | 1,674.4 |

| Source: Sporting Life | ||||

Joe Rice proved himself to be a worthy addition to the race when, on the Friday, a delegation of Wilkes-Barreans travelled to New York to cheer on his final hours. His fan club was said to be made up of merchants and politicians, coal operators and turf men, lawyers and railroad men – basically all levels of Wilkes-Barre’s populace. Between them their net worth was put at $14,000,000. However much of that number was an exaggeration is unknown; what is clear is that they had money to burn and between them raised a purse of $1,000 for the man who was helping to put their town on the cycling map.

The New York Times reported the Wilkes-Barre delegation as follows:

A delegation from Wilkesbarre arrived last evening [Friday]. With large white ribbons bearing the word ‘Wilkesbarre,’ 40 of the young miner’s friends sauntered about the arena cheering their favourite. A male quartet sang topical songs, which always ended with: ‘One, twice, thrice, R-I-C-E, Rice, Who are we? Who are we? Rice’s friends from Wilkesbarre.”

As the race drew to its close, as Saturday afternoon faded into Saturday evening, evening into night, the Garden filled out and the capacity 12,000 crowd cheered the remaining riders. The crowd was drawn from every strata of New York society:

Moving, pushing, choking in an atmosphere of tobacco smoke were heterogeneous thousands that could have gathered nowhere else than on Manhattan island. Many of the Four Hundred were there, the Bowery was there in force. Old gentlemen who ride bicycles jostled and elbowed toughs and bartenders. Clerks and prize-fighters, women from Merry Hill and Cherry Hill, children, girls in sable and young women in calico, were there.”

By now the riders were off their bikes more than they were on, resting more than they were riding. And when they were riding they were crawling around the Garden’s wooden oval at no great speed. But still the crowd roared and cheered, clapped their hands and stomped their feet. The spectacle of wheel-to-wheel racing had been replaced by the spectacle of human suffering:

“The end saw twelve human wrecks. Never did men finish a long-distance race so terribly exhausted. Some of them were raving lunatics.”

| 1896 Madison Square Garden International Six Day Race Final Position at Ten PM, Saturday, December 12 (142 hours) | ||||

| Name | Nationality | Kilometres Added | Total Kilometres | |

| 1 | Hale | Ireland | +408.0 | 3,075.1 |

| 2 | Rice | America | +433.7 | 3,029.8 |

| 3 | Reading | America | +433.2 | 2,985.8 |

| 4 | Forster | Germany | +357.3 | 2,944.1 |

| 5 | Schock | Germany | +322.5 | 2,842.4 |

| 6 | Pierce | Canada | +417.8 | 2,829.4 |

| 7 | Smith | America | +370.1 | 2,823.9 |

| 8 | Taylor | America | +334.6 | 2,787.7 |

| 9 | Ashinger | America | +338.4 | 2,693.7 |

| 10 | Moore | America | +259.3 | 2,674.2 |

| 11 | Maddox | America | +321.1 | 2,646.2 |

| 12 | Cassidy | America | +367.6 | 2,583.0 |

| 13 | Gannon | America | +249.8 | 2,199.7 |

| 14 | McLeod | Scotland | +314.6 | 2,172.9 |

| 15 | Glick | America | +90.0 | 1,764.3 |

| Source: Sporting Life | ||||

The final three hours of racing had seen less and less actual racing take place. The distances at seven, eight and nine o’clock were all reported in the press and make you wonder just how the 12,000 spectators who crowded the Garden maintained their excitement:

| 1896 Madison Square Garden International Six Day Race The Final Hours | ||||||||

| 7 PM | 8 PM | 9 PM | 10 PM | |||||

| Total Kms | Kms Added | Total Kms | Kms Added | Total Kms | Kms Added | Total Kms | ||

| Hale | Ireland | 3,024.0 | +19.6 | 3,043.6 | +19.6 | 3,063.2 | +11.9 | 3,075.1 |

| Rice | America | 2,985.3 | +19.2 | 3,004.5 | +16.9 | 3,021.4 | +8.4 | 3,029.8 |

| Reading | America | 2,953.5 | +20.6 | 2,974.1 | +11.7 | 2,985.8 | +0.0 | 2,985.8 |

| Forster | Germany | 2,910.2 | +19.2 | 2,929.3 | +14.0 | 2,943.3 | +0.8 | 2,944.1 |

| Schock | Germany | 2,820.7 | +15.4 | 2,836.1 | +6.3 | 2,842.4 | +0.0 | 2,842.4 |

| Pierce | Canada | 2,764.0 | +14.5 | 2,778.5 | +25.6 | 2,804.1 | +25.3 | 2,829.4 |

| Smith | America | 2,807.0 | +14.6 | 2,821.7 | +2.3 | 2,823.9 | +0.0 | 2,823.9 |

| Taylor | America | 2,752.5 | +14.0 | 2,766.5 | +6.3 | 2,772.7 | +15.0 | 2,787.7 |

| Ashinger | America | 2,657.0 | +19.0 | 2,676.0 | +12.9 | 2,688.9 | +4.8 | 2,693.7 |

| Moore | America | 2,627.9 | +26.1 | 2,654.0 | +15.1 | 2,669.1 | +5.1 | 2,674.2 |

| Maddox | America | 2,622.6 | +21.6 | 2,644.2 | +2.1 | 2,646.2 | +0.0 | 2,646.2 |

| Cassidy | America | 2,555.2 | +21.1 | 2,576.2 | +6.8 | 2,583.0 | +0.0 | 2,583.0 |

| Gannon | America | 2,177.3 | +5.3 | 2,182.6 | +16.1 | 2,198.7 | +1.0 | 2,199.7 |

| McLeod | Scotland | 2,154.4 | +5.6 | 2,160.1 | +12.9 | 2,172.9 | +0.0 | 2,172.9 |

| Glick | America | 1,755.0 | +9.3 | 1,764.3 | +0.0 | 1,764.3 | +0.0 | 1,764.3 |

| Source: Sporting Life | ||||||||

Having passed the 1,900 mile barrier – a little over 3,000 kilometres – at about 8.40 p.m. and being more than 40 kilometres clear of second-place Rice, Hale took the rest of the race easy, riding around the track carrying in his teeth

a gaudy banner of red and green and blue and silver, a combination of the Irish, English and American colours. He looked like a ghost on a phantom wheel, but his indomitable pluck sustained him. Hale’s face was white and wan. He looked straight ahead, his legs, his wonderful legs, moving with the regularity of a steamboat’s walking beam. But his mind was weaker than his legs. He was an automaton of flesh and blood – a man machine.”

For all that, the reporters covering the race managed to make its finale sound exciting:

Fully 12,000 persons were on hand to see the finish, and the enthusiasm was of a cyclonic nature. As the weary travellers circled the track during the last few hours they were cheered to the echo, and the ovation they received stimulated them to final bursts of speed, regardless of sore limbs, and aching muscles. Teddy Hale, the phenomenal Irish rider, finished in front.

In spite of the fact that he set the pace almost from the beginning of the race, he rode strongly at the end and concluded his effort with a whirlwind sprint. Irishmen were out in force, and whenever the band played ‘The Wearing of the Green’ they shrieked until their lungs ached and indulged in good old-fashioned reels.”

When the pistol shot sounded signifying the end of the race, Hale dismounted and, with Shock by his side, walked around the pine oval one last time, taking in the applause of the crowd and thanking them for their support.

As for Schock, the “old-time pedestrian, long distance bicycle rider and citizen of powerful legs and great endurance,” while he had failed to finish higher than fifth he was ahead of his own distance record. His entrée into the world of cycling had been through long distance foot races. He and Hale shared a background on high wheelers, and like Hale he had been one of the best on the circuit. Time and technology were outmoding him, though, and a new generation of rider, more able to ride a higher gear and still grind out the miles, was taking his place. But Schock’s day was not yet done and, within the year, he would regain many of the distance records Hale had taken from him during that Garden Six.

After the Six had ended at ten o’clock, the crowd had more exhibition races to amuse them. And then the lights went out and the curtain closed on the sixth Madison Square Garden International Six Day Race.

* * * * *

By the end of the nineteenth century, Victorians believed that theirs was the best the world would get, that all the technological innovations that man could ever devise had been already been divined. There was even talk of closing the patent office. So here it’s worth amusing ourselves with how the New York Times considered the speed of the cyclists during that Garden Six:

Fourteen miles an hour, then [Hale’s average speed, give or take], may be taken as at present the highest average speed that can be maintained on the bicycle, as a little over four miles and a half is the highest that can be maintained on foot, for a period of four days, with the time for sleep and food reduced to a minimum. These physical needs are constant, it is true, while the bicycle is presumably improvable. It does not seem likely, however, that any very great improvement remains to be made in the elimination of friction. The gearing may conceivably be improved so as to make the machine cover a greater distance for each stroke. It is noteworthy that Hale’s rivals have attributed his long lead to the uncommonly high gear he uses.”

The physical condition of the riders at the end of the race was also pored over. Dope, distance, sleep deprivation, all had driven them half mad during the dying days of the race, and the newspapers made much of this during the race and then sought to debunk it immediately after:

According to ‘Teddy’ Hale, it does not hurt a man so much to win the championship of the world in a six-day bicycle race. It makes him very tired, of course, and his knees may grow stiff and his throat sore. That was all the matter with the tall young Irishman yesterday [Monday]. He didn’t show his fatigue, though, and no one would have known that his knees were a bit stiff to see him walk. When he spoke, however, it was apparent that the cigar smoke in the Garden had done its work.”

La Vélo – at that stage the pre-eminent French sports newspaper, yet to face the challenge of L’Auto-Vélo and the uppity Henri Desgrange – reported the 1896 Garden Six sniffily, calling Six Day racing “a cruel sport” and bemoaning “the lamentable scenes of horror which marked the final hours of this indescribable spectacle.” Elsewhere in the French media the race was described as having been “one of the worst tortures that one could possibly ask a human being to undergo.”

That same year the French had unleashed Paris-Roubaix upon the cycling world, then not the Hell of the North, its cobbled roads merely affording easy preparation ride for the monstrously hard Bordeaux-Paris, which had been launched away back in 1891, and which itself was nothing when compared to the 1,200 kilometres of Paris-Brest-Paris. Knowledge of those races makes you want to construct a sentence containing the words ‘pot,’ ‘kettle,’ and ‘black’ when you consider the French reaction to the Garden Six.

That’s not to say that the French were wrong: Sixes were a cruel sport. That cruelty would be recognised by legislators within a few years, in both New York and Chicago. In New York, legislation was passed which aimed to stop riders from being on their bikes for more than twelve hours in a day. Some promoters responded to the changing legislative climate by reverting to Sixes with scheduled breaks: in 1900/1901 Boston had a New Year’s Six which had two five-hour sessions a day for the six days. But the promoters of the Garden Six refused to be beaten by the law and came up with a novel solution in 1899: they could still keep the riders on the track 24 hours a day if they put them in teams of two. Thus was born the Garden’s lasting legacy to cycling, the Madison.

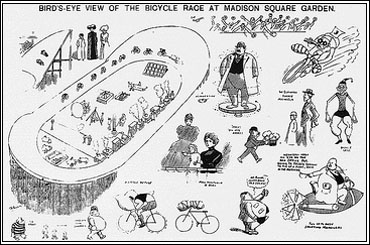

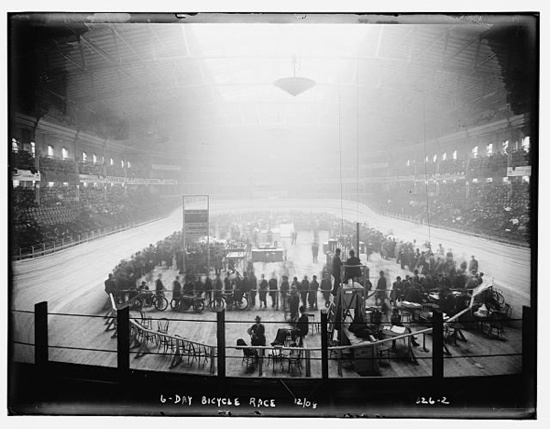

“Bird’s-eye View of the Bicycle Race at Madison Square Garden.” Illustration from The World newspaper, 1901, depicting the Garden’s wooden oval and its banking.

Whether the Garden Six was a cruel and unusual punishment or not, the simple fact is it rewarded well. On the Monday after the race, the riders gathered in the Hotel Bartholdi for the presentation of the prizes. For finishing first Hale pocketed $1,300 in gold double eagle coins, too many to fit in his pockets; the rest he had to cram into a cap to carry. In total, after adding in sponsor bonuses and other prizes for setting various records along the way to victory, the win was estimated to have been worth $3,800 to the Irishman.

Rice pocketed $800 for his second place, on top of the $1,000 raised for him by his Wilkes-Barre supporters. Reading pocketed $500 for third, as well as the $50 he won for staying his bike for a record distance. $350 went to Forster for fourth, $300 to Schock, $200 to Pierce, $150 to Smith, $125 to Taylor, $100 each to Ashinger and Moore, and $75 to Maddox. The promoters, feeling generous, then decided to award $75 to each of the remaining four riders – Cassidy, Gannon, McLeod, and Glick. All bar the last three riders had beaten Schock’s 2,575 kilometre record, and that must have given the promoters good reason to feel generous.

Hale also had a chance to cash in on his new-found fame with the Garden’s equivalent of the post-Tour critérium circuit. Hale, along with Tom Linton, went on the vaudeville circuit and was immediately booked into Proctor’s Pleasure Palace, probably for a series of roller races, the stationary bikes hooked up to a big display behind the riders which counted off the miles they pedalled in virtual races. For the unlucky riders, it was more of the same, with the Garden Six being followed by Sixes in Baltimore and Washington and then onwards around the country until the championship season got underway.

The promoters themselves – Pat Powers, Bill Brady, and Jerry Kennedy – didn’t do too badly out of the race either. Gate receipts were estimated to be $37,000: as one newspaper reported, the promoters “made hay while the electric light shone and increased the price of admission,” from 50¢ to $1 as the weekend drew near. The crowd packing the Garden would wax and wane as the race wore on. As many as 3,000 would stay there all night, that number doubling by noon. Through the afternoon another couple of thousand would arrive until by the height of the evening as many as 10,000 would fill the Garden. As the race drew toward its conclusion daily attendances increased, with the final session pulling in 12,000 punters.

In all, just over $7,000 was estimated to have gone on prizes, for the riders in the Six itself and the exhibition events that took place before, during and after it. The cost of organising the race was put at another $20,000, leaving $10,000 profit to be shared out between Powers, Brady, and Kennedy. If $20,000 seems like a high cost for organising the race, then consider the various bills that had to be paid. Hiring the Garden itself wasn’t cheap – it was a premiere venue and Powers, Brady, and Kennedy were not the only ones who wanted to organise bike races there. Then you have to add in the appearance fees that had to be paid to some of the riders, particularly the international ones, to cover their travel and accommodation expenses and generally make it worth their while to turn up. Then consider that the track wasn’t a permanent structure, it was put up days before the event and pulled down immediately the race was over, the timber boards being sold for firewood. Then add in the staffing costs to run the venue 24 hours a day for a full week: one estimate put the figure at 500 staff being employed over the course of one of the Garden’s Sixes.

So yes, for sure, a $10,000 profit made putting on the Garden Six a worthwhile endeavour – and, yes, raised calls for greater revenue sharing from the riders – but a lot of capital was risked to make that profit, which could have easily turned into a loss if the punters didn’t have reason enough to keep pushing through the turnstiles each day.

For the most part that situation would not arise so long as the riders did what they were paid to do: put on a show. But, when the riders failed to live up to their billing, then the promoters had to work some magic. For the Grand Tour organisers in later years, that magic was easy enough to manufacture: their own newspapers reported their races. The European Grand Tour organisers were blessed by few people actually witnessing what was really going on in their races and so could exaggerate stories to create the myths of les géants de la route. For Brady and his partners, magicking up interest in their races sometimes necessitated feeding New York’s hungry yellow press the sort of stories they specialised in: scandal. Like the Italians, the New York promoters were dab hands at producing polemica on demand.

* * * * *

So what happened to Teddy Hale after the 1896 Garden Six was over?

As noted, immediately the race was over he went on the vaudeville circuit, converting his fame into hard currency. He was reported to have signed with the Peerless company and would be riding their bikes in all long distance races up to April, more money banked on the back of his win in the Garden. He was then reported to be riding the rollers at the Brooklyn Bicycle Show, alongside Charles Murphy. On February 6 Hale was defeated by Louis Gimm in a 100 mile race at the Central Armory, Cleveland, Ohio. Then he took part in the Chicago Six where he failed to finish. Shortly after that he was reported to have sailed for England, with the intention of returning to the States in six weeks. His plans for the season ahead were said to see him specialising in road work.

In August Hale was reported to have issued a challenge to JF Stocks, a $500 purse for a race over six hours at the Catford track. In October he was reported to be in Australia, with no immediate plans to return to America. But, by the time the 1897 Garden Six came around, the Irishman was back in New York, where reports said he had completed a season racing in Britain, Europe and Australia.

At the 1897 Garden Six Charles Miller stuffed another 294 kilometres onto Hale’s record from the year before, bringing the distance up to 3,369 kilometres. Hale himself surpassed his own performance from the year before, covering 3,090 kilometres but that was only good enough for fourth place. Illness had kept him off the track for considerable periods early in the race and the rest of the week he spent playing catch up. Still, his performance earned him $350, which was not quite an unprofitable week’s work when you consider that, back then, a couple of hundred dollars was enough to make you a swell.

No sooner was the 1897 Garden Six over than the real fun began: it was discovered that the track was short. Measuring tracks is never easy and track measurements are often disputed. Most famously, Oscar Egg retained his Hour record in 1913 by crawling around a track on his hands and knees, ruler in hand, measuring the distance and proving that the track was short. It didn’t take someone crawling around on hands and knees, but the same was found true of the track erected for the 1897 Garden Six and the race results had to be rewritten. Miller’s 3,369 kilometres were pegged back to 3,192 kilometres: still ahead of Hale’s record but now by just 117 kilometres. The revisions meant that Hale finished short of his own record, his revised distance being 2,928 kilometres.

In 1898 – the last year the Garden Sixes were run as solo races – Hale was again back in the Garden, alongside two other Irish riders, Henry Pilkington and James Nawn. This time Hale was well down on his best, only managing 2,335 kilometres and finishing away down in eleventh place. A few weeks later Hale was again racing on the Garden’s boards when took part in a 24 hour race.

After that, Hale begins to slip from recorded history. At the end of July, 1899, he set out on an attempt to ride a century a day every day (bar Sundays) for a full year. This was done in England, mostly – it seems – down on the South coast. The endeavour was a publicity stunt for the Acatene chainless bike Hale was riding. The bike was described as having “Dunlop tyres, a Christy saddle and an 84 gear. The machine weighs 36 lbs and is fitted with two handlebars of the dropped and raised order respectively, for speedy work or leisurely riding at will.” Hale was reported to be riding on “chops and steaks and good old English beer, with Taddy’s tobacco to solace the monotony.”

And that’s just about it from Hale. There’s a mention of him from 1903, when he was reported to be in the bicycle business, somewhere in England. What became of him after that is currently unknown.

| Madison Square Garden International Six Day Races | |||

| Year | Date | Winner | Kilometres |

| The ‘High Wheeler’ Years | |||

| 1891 | Oct 19-24 | William ‘Plugger Bill’ Martin | 2,360 |

| 1892 | Mar 7-12 | Charles W Ashinger | 1,646 |

| 1893 | Dec 25-30 | Albert Schock | 2,575 |

| 1894 | Nov 27-Dec 1 | Charles Ashynee | |

| The ‘Safety’ Years | |||

| 1895 | Albert Schock | ||

| 1896 | Dec 7-12 | Edward ‘Teddy’ Hale | 3,075 |

| 1897 | Dec 6-11 | Charles W Miller | 3,192 |

| 1898 | Dec 5-10 | Charles W Miller | 3,158 |

| The ‘Madison’ Years | |||

| 1899 | Dec 4-9 | Charles Miller / Frank Waller | |

| 1900 | Dec 10-15 | Floyd McFarland / Harry Elkes | |

| 1901 | Dec 9-14 | Bobby Walthour / Archie McEachern | |

| 1902 | Dec | Georges Leander / Floyd Krebs | |

| 1903 | Dec | Bobby Walthour / Ben Moore | |

| 1904 | Dec | Eddy Root / Oliver Dorlon | |

| 1905 | Dec | Eddy Root / Joe Fogler | |

| 1906 | Dec | Eddy Root / Joe Fogler | |

| 1907 | Dec | Walter Rütt / John Stohl | |

| 1908 | Dec 7-12 | Jim Moran / Floyd McFarland | |

| 1909 | Dec 6-11 | Walter Rütt / Jackie Clark | |

| 1910 | Dec 5-10 | Eddy Root / Jim Moran | |

| 1911 | Dec 10-15 | Jackie Clark / Joe Fogler | |

| 1912 | Dec 9-14 | Walter Rütt / Joe Fogler | |

| 1913 | Dec 8-13 | Alf Goullet / Joe Fogler | |

| 1914 | Nov 16-22 | Alf Goullet / Alfred Grenda | |

| 1915 | Dec 5-11 | Alfred Hall / Alfred Grenda | |

| 1916 | Dec | Marcel Dupuy / Oscar Egg | |

| 1917 | Jan 3-8 | Alf Goullet / Jake Magin | |

| 1918 | Reggie McNamara / Jake Magin | ||

| 1919 | Nov 30-Dec 5 | Alf Goullet / Eddie Madden | |

| 1920 | Nov 22-27 | Alf Goullet / Jake Magin | |

| 1920 | Dec 5-11 | Maurice Brocco / Willy Coburn | |

| 1921 | Mar 7-13 | Piet van Kempen / Oscar Egg | |

| 1921 | Dec 5-10 | Alf Goullet / Maurice Brocco | |

| 1922 | Mar 6-3 | Reggie McNamara / Alfred Grenda | |

| 1922 | Dec 3-8 | Alf Goullet / Gaetano Belloni | |

| 1923 | Mar 5-10 | Alf Goullet / Alfred Grenda | |

| 1923 | Sep 3-8 | Ernst Kockler / Percy Lawrence | |

| 1924 | Mar 3-8 | Maurice Brocco / Marcel Buysse | |

| 1924 | Dec 1-7 | Reggie McNamara / Piet van Kempen | |

| 1924 | Dec 31-Jan 5 | Reggie McNamara / Piet van Kempen | |

| 1925 | Mar 1-7 | Bobby Walthour Jnr / Fred Spencer | |

| 1925 | Nov 29-Dec 5 | Gérard Debaets / Alfons Goosens | |

| 1926 | Mar | Reggie McNamara / Franco Gieogetti | |

| 1926 | Dec 5-11 | Reggie McNamara / Pietro Linari | |

| 1927 | Mar 6-12 | Reggie McNamara / Franco Gieogetti | |

| 1927 | Dec 4-10 | Charly Winter / Fred Spencer | |

| 1928 | Mar 5-11 | Gérard Debaets / Franco Gieogetti | |

| 1928 | Dec 3-9 | Franco Gieogetti / Fred Spencer | |

| 1929 | Jan 12-18 | Dave Lands / Willie Grimm | |

| 1929 | Mar 4-10 | Gérard Debaets / Franco Gieogetti | |

| 1929 | Dec 1-7 | Gérard Debaets / Franco Gieogetti | |

| 1930 | Dec 3-9 | Gérard Debaets / Gaetano Belloni | |

| 1930 | Nov 30-Dec 5 | Paul Broccardo / Franco Giorgetti | |

| 1931 | Mar 1-6 | Alfred Letourner / Marcel Gumbretiere | |

| 1931 | Nov 30-Dec 5 | Alfred Letourner / Marcel Gumbretiere | |

| 1932 | Feb 28-Mar 5 | Reggie McNamara / William ‘Torchy’ Peden | |

| 1932 | Nov 28-Dec 3 | Fred Spencer / William ‘Torchy’ Peden | |

| 1933 | Feb 27-Mar 5 | Gérard Debaets / Alfred Letourner | |

| 1933 | Nov 26-Dec 2 | Alfred Letourner / William ‘Torchy’ Peden | |

| 1934 | Feb 25-Mar 2 | Paul Broccardo / Marcel Guimbretiere | |

| 1934 | Dec 2-8 | Gérard Debaets / Alfred Letourner | |

| 1935 | Mar 3-9 | Franco Giorgetti / Alfred Letourner | |

| 1935 | Dec 2-8 | Gustav Kilian / Heinz Vöpel | |

| 1936 | Feb 23-29 | Gustav Kilian / Heinz Vöpel | |

| 1936 | Nov 29-Dec 5 | Jimmy Walthour Jnr / Alfred Crossley | |

| 1937 | Mar 1-6 | Jean Aerts / Omar de Bruyckner | |

| 1937 | Nov 30-Dec 5 | Gustav Kilian / Heinz Vöpel | |

| 1938 | Sep 19-25 | Gustav Kilian / Heinz Vöpel | |

| 1939 | May 15-20 | William ‘Torchy’ Peden / Doug Peden | |

| 1939 | Nov 20-25 | César Moretti Jnr / Cecil Yates | |

| 1948 | Feb 26-Mar 2 | Alvaro Giorgetti / Angel de Bacoo | |

| 1948 | Oct 17-23 | Emile de Bruyneau / Louis Saen | |

| 1948 | Nov 15-20 | Alvaro Girogetti / César Moretti Jnr | |

| 1949 | Feb 28-Mar 6 | Hugo Koblet / Walter Digglemann | |

| 1949 | Oct 30-Nov 4 | Alfred Strom / Reginald Arnold | |

| 1950 | Mar 1-7 | Ferdinando Teruzzi / Serverino Rigoni | |

| 1959 | Mar 20-26 | Ferdinando Teruzzi / Leandro Faggin | |

| 1961 | Sep 22-27 | Oscar Plattner / Armin von Büren | |

| Sources: Memoire du Cyclisme & SixDay.org Note: The above table seems to contain some errors. All the dates need to be checked, and there should only be 75 Madison Square Garden International Six Day Races. | |||

* * * * *

Cycling is a sport built on myths and it will probably come as no surprise when I tell you that some of this tale must be taken with a pinch of salt. Until all the victories claimed by Hale have been verified some doubt must attach to them: cyclists, like fishermen, exaggerate. The part, though, that is most open to question is Teddy Hale himself, and just how Irish he was. Barely a month after the 1896 Garden Six was over Sporting Life carried this notice:

“An Irish newspaper says that Teddy Hale, who won the recent six-day race and who is now appearing at the Bijou, this city [New York], was not born in Ireland and never so much as set foot on Irish soil.”

British newspapers and cycling media carried similar claims. Does this mean that Hale was as Irish as Tony Cascarino (the Maltese-born footballer who managed to play for Ireland, without even fulfilling the requirements of the grand-parents rule)? Maybe, maybe not.

I could point out here that three of the best of the current crop of Irish riders – Daniel Martin (Garmin), Nicolas Roche (AG2R), and Matt Brammeier (Quickstep) – are children of the diaspora and no less Irish for not having been born on the island. Irishness can be quite confusing sometimes, even for Irish people: Ian Moore, the Belfast-born rider who participated in the Tour in 1961, is often over-looked when people list Irish riders who participated in la grande boucle. Irishness – and the denial of Irishness – can often be a political statement as much as a flag of convenience.

It is entirely possible that Hale’s Irishness was an invention of the New York promoters. It was not unknown for them to flex the nationalities of riders to suit the crowd they wanted to draw. Frank Waller, for instance, seems to have varied between being an American, a German, and a Dutchman. Albert Shock was sometimes American, sometimes German, as was Charles Miller.

Whatever the truth of his Templepatrick roots, Hale certainly flew the flag for Ireland, of that there’s no doubt: in that 1896 Garden Six he raced in a suit of green, rode to the tune of ‘The Wearing of the Green’ and was welcomed by New York’s Irish societies. But if Hale’s Irishness was an invention then it was one that has stuck, for after that 1896 Garden Six Hale is almost always reported as being Irish.

* * * * *

So if the claim that Hale was Irish can be disputed what of my assertion that the Madison Square Garden International Six Day races were America’s Grand Tour, before Europe’s Grand Tours were even dreamt of? On distance and difficulty, the Garden Sixes easily compare to Grand Tours: the Tour today is only four of five hundred kilometres longer than the distance Hale ground out in the 1896 Garden Six.

Does the fact that the Garden Sixes lasted only Six Days invalidate them? Consider, though, how much saddle time was involved: 142 hours of racing with eight hours sleeping still leaves the riders in those solo Sixes clocking far more saddle time than the winners of modern Grand Tours, who typically spend fewer than 100 hours on their bikes. And the riders in those solo Sixes were on their own, no domestiques, gragari or campañeri to break wind and pass water for them.

For sure, the Garden Sixes lacked climbs, their highest altitude being 10 or 15 feet if you went to the top of the banking. Hale was reckoned to have spent most of the race taking the long way round, the outside of the track, high on the banking, adding an estimated 55 kilometres to the distance he covered. If you allow him 20 feet of altitude gain each lap, then his 19,108 times around the Garden’s pine oval were worth more that 115,000 metres of altitude gain. What’s that, more than a hundred times up Alpe d’Huez? Ok, so the two don’t really compare, the Garden’s banking being but a pimple on a gnat’s arse compared to the Alpe. But is it really climbing that makes a Grand Tour? The early Tours lacked climbs and it took both the Giro and the Vuelta quite some time to really find their climbing feet. So no, climbing isn’t essential in order to be considered a Grand Tour.

If the direct comparisons don’t work for you then consider the role the Sixes played in the birth of the Grand Tours. Six years after that 1896 Garden Six ended, six years after Le Vélo had written sniffily of its excesses, in an office in the Montmartre district of Paris a former staffer with Le Vélo, Géo Lefèvre, punted an idea to his current editor, Henri Desgrange, that of putting on a Six Day race on the roads of France, the riders racing from Paris to Lyon and then on to Marseille, Toulouse, Bordeaux and Nantes before racing back into Paris, 2,500 kilometres of racing after they’d left it.

Sixes hadn’t at that point taken root in mainland Europe: Berlin didn’t get a Six until 1909, followed by Bremen in 1910, Frankfurt in 1911 and Brussels in 1912, with Hanover and Paris joining the party in 1913 (there was an attempt to organise a Six in Toulouse, in 1906, but that was cancelled after three days of racing). In punting the idea of a Six Day race on the roads of France Lefèvre seems to have been looking beyond France’s borders for inspiration. And of all the Sixes the Garden Six was the one most widely reported in the French press. From a seed first sown in England, then nourished in the United States and exported to Australia, the Tour de France was born, years before Sixes flourished in cycling’s Continental heartlands.

As the Tour de France established itself in the history of our sport, the stars it forged crossed the Atlantic to ride on the wooden boards of the Madison Square Garden track. As did stars of the Giro d’Italia. Hugo Koblet and Gaetano Belloni both won there. Other Grand Tour stars to work the boards include Lucien Petit-Breton, Costante Girardengo, Octave Lapize, Learco Guerra, Lucien Buysse and Alfredo Binda.

And, having loosely borrowed its format from the Six Day races, the Tour de France then raided the Sixes for other innovations: mid-stage sprint primes originated on the boards, a way of taking the tedium out of the tired hours of riding when the group preferred to just roll around the track at their own pace, punters waving dollars in the air like Johns in a strip-bar, the riders having to shake their booty and sprint to win them.

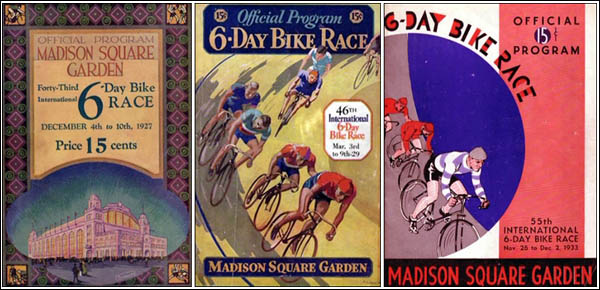

Three programmes from Madison Square Garden International Six Day Races, 1927, 1929 and 1933. Source: Peter Nye’s The Six Day Bicycle Races (Van der Plas Publishing / Cycle Publishing)

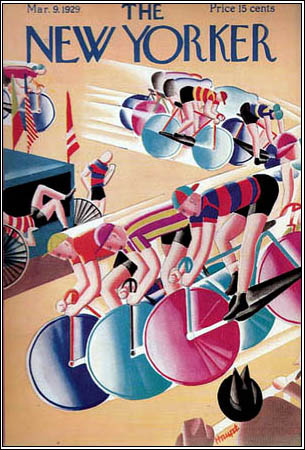

The Garden Sixes also compare to the Grand Tours in the manner in which they were reported. The Tour had Antoine Blondin and the Giro had Dino Buzzati spinning panegyric prose in their honour. Through America’s Jazz Age of the 1920s the Garden Sixes were reported by some of the leading lights of the American newspaper trade, including Damon Runyon and James Thurber. Right at the peak of their popularity, in March 1929, six months before the sky fell in and Wall Street crashed, the New Yorker magazine, the bible of America’s literati, gave over its front cover to the Spring Six in the Garden. Six decades on and American cycling fans thought their sport was popular when Greg LeMond made the cover of Sports Illustrated? They didn’t know they were born.

The cover of the March 1929 edition of The New Yorker magazine, celebrating the 1929 Spring Six in Madison Square Garden. Source: The New Yorker.

The Madison Square Garden races should not just be considered as a little bit of American cycling history, something just for American cycling fans to revel in. Nor is my focusing on Teddy Hale’s 1896 victory just an attempt to show they play a part – however questionable – in Irish cycling history. The Garden Sixes were – are– fully a part of all of cycling’s history. They should be remembered for the inspiration they afforded the founders of the Tour. But they should also be remembered because they were as hard and as exciting as the Grand Tours they inspired. And the heroes they created easily deserve to be up there with the pantheon of Grand Tour winners.

* * * * *

Sources: I’ve known of Teddy Hale since I first read Peter Nye’s Hearts of Lions and have seen him name-checked in most other books I’ve read that talk of this part of cycling’s history, but none offered any real information on who he was and what became of him. For the most part this story was built up from newspaper and magazines that reported the 1896 Garden Six while it was on, and those that remembered Hale in the years after 1896. Right now, this is only scratching the surface of Hale’s story, using easily accessible resources. There’s a lot of information on Hale yet to be rediscovered, from both before and after the 1896 Garden Six.

The 1896 Garden Six features in at least two of the Major Taylor books, the Garden having been where he made his pro debut. Credit then to Major Taylor – The Fastest Bicycle Rider In The World, (Van der Plas Publishing / Cycle Publishing, 1988) by Andrew Ritchie and Major – A Black Athlete, A White Era, And The Fight To Be The World’s Fastest Human Being (Crown, 2008) by Todd Balf.

Additional information has been drawn from Peter Nye’s Hearts Of Lions – The Story Of American Bicycle Racing (Van der Plas Publishing / Cycle Publishing, 1988) and The Six Day Bicycle Races – America’s Jazz-Age Sport (Van der Plas Publishing / Cycle Publishing, 2006), as well as Gerry Moore’s Little Black Bottle – Choppy Warburton, The Question Of Doping, And The Deaths Of His Bicycle Riders (Van der Plas Publishing / Cycle Publishing, 2011), Sue Macy’s Wheels of Change – How Women Rode the Bicycle to Freedom (With a Few Flat Tires Along the Way) (National Geographic, 2011) and Andrew Homan’s Life In The Slipstream – the Legend Of Bobby Walthour Sr (Potomac Books, 2011).

Online sources include Memoire-Du-Cyclisme.net, SixDay.org and SixDay.org.uk as well as various online newspaper and magazine archive resources.

If you want to correct any of the errors I’ve doubtless made, you’ll find me on Twitter, @fmk_RoI.

2 Comments

[…] from the fallout of the Black Sox scandal and lost some popularity, allowing cycling, particularly the Six Day races in Madison Square Garden, to again came to the fore. Baseball, though, immediately learned a lesson that it took the Festina […]

[…] isn’t exactly renowned for its track stars. We do have some history; there’s Teddy Hale‘s exploits in America’s Grand Tour and Shay Elliott‘s early years, when he set […]