By the time Marty Nothstein hung up his wheels in 2006 he was the most decorated American track cyclist of all time. In his time he had won thirty-five national championships. He’d won gold in the Pan-American Games four times. He was a triple World Champion. He was the first American to win the professional sprint World Championships in eighty years. He was the first American to win a Six Day race in half a century. And he was an Olympic gold medallist.

It’s said that one of the key benefits of hosting the Olympic Games is that the host nation pours a ton of money into sport in the hope of showing the world just how brilliant they really are. The investment starts as soon as the host city is announced and the legacy is supposed to last for years after. Host the Games and, across a range of sports, you should produce a generation of talent.

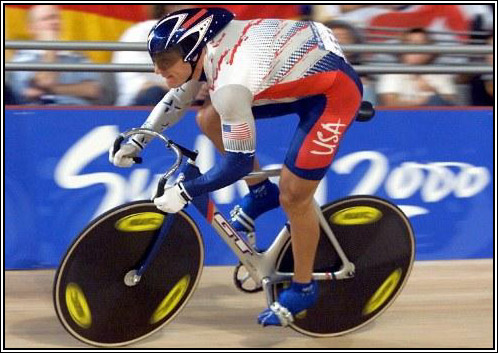

At the 1996 Atlanta Games US cycling threw a pot full of money – hundreds of thousands of dollars – at the Games in the hope of buying gold. EDS and GT Bicycles teamed up to produce the Superbike, a state-of-the-art light-weight carbon-fibre speed machine. Like many Superbike projects – think, perhaps, Lance Armstrong’s infamous F-One project – it was money down the drain. Going into the last day of the track competitions all USA Cycling had to show for their effort was one lump of metal: Erin Hartwell’s silver in the kilometre time trial. And then came Marty Nothstein’s shot at glory in the individual sprint.

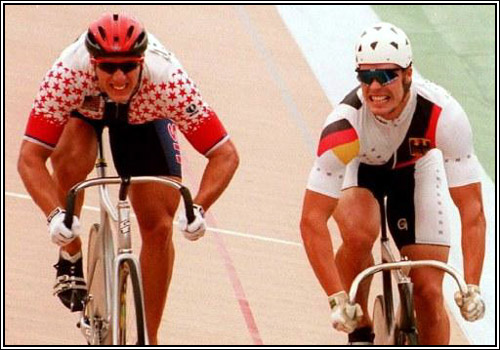

Nothstein is up against the reigning Olympic champion, Jens Fiedler, a product of the East German medal factory. Fielder’s a protégé of Lutz Hesslich, himself the Olympic champion in ’80 and ’88 (the East Germans boycotted the LA ’84 Games, payback for the Western boycott of Moscow ’80). Nothstein himself has his own Eastern Bloc coach, USA Cycling’s sprint coach, the Pole Andrzej Bek, a tandem bronze medallist at Munich ’72.

In a test of pure speed, Nothstein should be able to beat Fiedler. But sprinting isn’t just speed. It’s nerve and tactics too. And tactically the German is the superior rider.

I say a prayer, as I do before every race, not to crash. I pray my competitor and I will stay safe. I’m not especially religious, but if there’s a time to believe in God, this is it. […] I prayed we won’t get hurt, but I want to kill him. I want to rip his fucking throat out. I want to win this race, and I want to make his death quick, decisive.”

In the first heat Fiedler leads off. Nothstein tries to take the lead and the two go elbow to elbow. The American backs down first and resumes his place in the German’s slipstream. The he tries a feint, moving to come around Fiedler on the outside before dipping on the in. The German blocks him, leaves Nothstein trailing in his wake. In the final lap Fiedler starts to wind it up to top speed. Out of turn one and into the back straight Nothstein’s closing on the German’s rear wheel. The he starts to pull out of the slipstream and fight though the dirty air.

Through the last turn he’s pulled level with Fiedler’s rear wheel. Fiedler pushes him high on the banking, taking the long way round, forcing Nothstein to go even longer. Fiedler’s above the sprinter’s red line, he tries to flick Nothstein. But the American’s ready. He’s well used to roughhousing it. They may be clocking seventy but Nothstein’s not backing off. In the home straight he’s up to Fiedler’s hip. Fifty metres out and every ten metres Nothstein’s closing on Fiedler’s front wheel a foot at a time. Five feet: he’s not down yet. On the line the American and the German are side by side, arms outstretched, heads down, arses up.

Photo finish. Say cheese and smile for the birdie.

The camera, shooting 10,000 frames per second, decides my faith. But I don’t need a camera to know I crossed the line first. Every racer knows whether they won or lost, no matter how close the finish. It’s instinctual. I’m my own camera. Even NASCAR drivers travelling 200 miles per hour can tell if they won or lost by an inch. But my victory is in the hands of the officials.”

After twenty minutes of scrutinising the photos the blazers call the sprint in Fiedler’s favour. One thousandth of a second. One centimetre. One nil, advantage Germany.

In the second heat it’s Nothstein’s turn to take the lead. That’s where he wants to be, where his turn of speed can leave Fiedler standing. Except the German jumps him on the start. In three pedal strokes he’s half a wheel up and again Nothstein is on the back foot. Again Nothstein is stuck in Fielder’s slipstream. Again the German holds off all the American’s attempts to take the lead as they lap the Stone Mountain track.

One lap to go. Fiedler’s weaving all over the track as I charge toward his rear wheel. He’s above the sprinter’s lane, below the sprinter’s lane. Never flagrant enough to draw the ire of the officials, just enough to keep me at bay. I’d do the same thing if I had the front. We round the last corner, and again I’m gaining ground on him. I’m the faster rider. I reach his hip, his shoulders, there’s the line. Fiedler beats me by half a wheel. He wins the gold medal. I lose.”

Note the “I lose” bit. Note that it’s not “I won silver.” Who really wants to be the first loser? Who really goes to the Games just to pick up one of the baser metals? To celebrate being given a consolation prize? If it was really the taking part that mattered, everyone would be on the podium. It’s only the winning that counts.

Confession time: I like sprinters. I like their self confidence. Maybe that’s a product of discovering this sport through Sean Kelly. You know what they say about your first love being the deepest? Maybe that’s me and sprinters. A lot of people, though, don’t like sprinters. They see them as arrogant, cocky bastards. Self confidence and arrogance, there’s a thin line between the two. Most of the sprinters I like fall on the right side of the line. Nothstein, in The Price of Gold, falls comfortably on the right side of the line. Take this bit, right after he’s been defeated by Fiedler:

As we let the gears spin out on our bikes, I ride next to Fiedler. I shake his hand. I rub his round white helmet. He pumps his fist in the air, triumphantly. It was a fair fight, a good match. I lost to a worthy competitor, one of the greatest Olympic track cyclists of all time.”

The day after his defeat in Atlanta, Nothstein started preparing for his second bite at the Olympic cherry: Sydney 2000. The day after his defeat in Atlanta, Nothstein reset his sights on the only colour that matters in the Olympics: gold.

The meat and two veg of The Price of Gold is the story of the four years between Atlanta and Sydney, and the sacrifices made along the way. The story of the years before Atlanta and after Sydney are the hors d’oeuvre and dessert.

Starters first. Nothstein comes from Pennsylvania Dutch stock, his family roots tracing back to the German-Deutsch immigrants William Penn enticed to Lehigh Valley in the years before the Revolutionary War. Typically, the PA Dutch are blue collar through and through. They understand the value of hard work. But the Protestant work ethic hasn’t turned them into Puritans. They drink and they brawl. Nothstein’s father was a drinker. The son became a brawler. Through brawling he became a cyclist.

In the 1970s Lehigh Valley became a Mecca for U.S. cycling when a former Olympic skeet shooter, Bob Rodale (of Rodale Press, publishers of Bicycling magazine and of The Price of Gold), donated twenty-five acres of farmland near Trexlertown – T-Town – to the county and built a vélodrome on it. Rodale had been bitten by the cycling bug and this was his gift to the local community: an outdoor concrete oval, a third of a kilometre round. Jack Simes – scion of one of America’s cycling dynasties – was appointed one of the new track’s directors. Friday nights at Lehigh Valley became cycling night. Even Eddy Merckx strutted his stuff in T-Town’s vélodrome.

The story of Lehigh Valley is something I’m only vaguely familiar with. Reading Bill Strickland’s Bicycling pieces, it’s a place that crops up time and again. It’s become somewhat familiar, though still somewhat vague in my mind. Nothstein’s description of the Valley fleshed the picture out a lot for me. Added focus. Made me want to learn more.

There’s a part of the way Nothstein sketches the history of Lehigh Valley that reminded me of Tom Wolfe’s description of the early days of Andrews Air Field in The Right Stuff. This is – no doubt – me carrying baggage to the table here. (Fact is, we all carry baggage with us to the table every time we pick up a book.) But there is something about the history of cycling in Lehigh Valley that recalls the early devil-may-care drinking-and-driving-and-flying years of the Andrews test pilots. Except in Lehigh Valley it was drinking-and-driving-and-cycling.

There’s a story Nothstein tells, a piece of Valley folklore, about the way T-Town drew in the best of the best, which recalls Wolfe’s description of the way Andrews drew in the flyboys. One night in 1980 a couple of SoCal cyclists, Gil Hatton and Pat McDonagh, climbed into a Plymouth Champ and headed east. Along the way they crashed, rolling the car in the desert after falling asleep at the wheel. They put the car back on the road, kicked out the shattered windscreen, tied bandannas round mouth and nose as bug shields, and continued on their way. When, days later, they pulled up in the gravel parking lot outside the T-Town vélodrome they looked a sight, dust-covered and in their thrashed car.

Another story for you:

One day in high school, I’m washing cars at my dad’s dealership, earning money for bicycle equipment, when a blue Ford Torino blows into the parking lot and launches off a three-foot slope separating the dealership from the house next door. The Torino slides to a stop in the neighbor’s gravel driveway.

From the plume of white dust the car kicks up, out steps a bike racer with a scraggly handlebar moustache and a shaggy head of red hair. I look at him in awe. That’s Whitehead. The Outlaw. Whitehead’s antics at the Friday night races inspire even reserved fans to boo and hiss. And he loves every minute of it. He flips the bird after crossing the finish line. He’s been ejected for hocking loogies at hecklers. And the louder the boos, the more Whitehead seems to win. […] I’ve never met Whitehead before, but I know that when he’s in town, stunts like this tend to occur regularly.

“Whitehead lives in California and is in T-Town for the wedding of his best friend, Gil Hatton. Together they’re the Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid of cycling. They’re crazy as hell, but calculated too. They don’t win bike races by accident. […] These are the bike racers I aim to emulate.”

All the regular’s in T-Town’s track nights earned nicknames. As well as the Outlaw there was the Bear. The Animal. The Torch. Art the Dart. Nothstein earned his nick in the keirin, slicing through the field to win from the back. He became the Blade.

T-Town’s races taught Nothstein a lot about track racing. But there was a problem with Nothstein learning his metier in the Valley’s Friday night bear-pit. In T-Town’s track races rules were seen as more like guidelines as the riders thrilled the crowd, throwing hooks, elbows, shoulders and head butts in the race for the line. Old school rough-and-tumble sprinting.

Problem is, the rules aren’t just guidelines in National and World Championships: they’re the rules. There to be enforced. Time and time again the young Nothstein lost because the aggression – the hooking and slicing – that helped him win in T-Town got him DQ’ed. And – again – here is something good about Nothstein’s telling of his tale: he recognises his own errors. Here he is after getting dumped out of the 1989 junior Worlds in Moscow after the second round:

I’m inconsolable. I worked so hard. I wanted a medal so badly, and it’s over just like that. Tears stream down my face and won’t stop. If I’d ridden clean, I could have won. But I didn’t control my aggression.”

The Price of Gold is all told in the first person present tense. That’s not just a tricksy stylistic flourish, a way of adding intensity to the story. You quickly feel that these aren’t memories being dragged up from the past for Nothstein. You quickly feel that the past is very much alive for him. That the pain and the pleasure is an ever-present vivid feeling. You quickly realise just how intense Nothstein himself is.

One of the benefits of the present-tense telling of the story is that Nothstein sucks you into his world, puts you there on the bike with him. This is something only a few cycling books pull off. The race descriptions The Price of Gold are well worth reading. Yes, they’re macho, testosterone-fuelled depictions of bike racing. Cycling as a boxing match. Cycling as hunting. But that’s track sprinting at its best: it’s the physicality of it that impresses the most. This is, after all, the side of cycling that attracted Ernest Hemingway in his Paris years.

Physicality doesn’t mean hooks and head butts and crashes (though let’s be honest here – hooks and head butts and crashes are part of the attraction): it’s about the explosive nature of sprinting after all the tactical foreplay. Some of that foreplay has been lost in recent years as track sprinting has commoditised itself into, repackaged itself for TV schedulers, all but banning track stands. But enough of it is still there for the best sprint matches to be a magical mix of balletic beauty and athletic ability.

So how did Nothstein get hooked on his single-minded pursuit of Olympic glory? That would have been with the 1976 Games. On the TV Nothstein watched Nadia Comaneci, Bruce Jenner, and Greg Louganis win golds in the Montréal Games:

I’m enthralled with the pageantry of the Olympics, the intensity of the competition. I’m only five and the Olympic dream is becoming my dream, already. An athlete bends forward as the gold medal is draped around his neck. The national anthem plays. I jump up on the coffee table and raise my arms, ‘I’m going to win the Olympics someday,’ I shout. Cute, my family thinks.”

It was years later, though, that the role the Olympics could play in Nothstein’s life really came home to him. As a kid Nothstein would go on hunting trips with his father and his father’s PA Dutch friends. Around the campfire, stories would be told. War stories, often. This was the 1980s and the men Nothstein’s father hunted with were veterans of America’s perpetual war for perpetual peace:

‘Listen to and respect these men,’ my father told me. ‘Serving your country is a great honor.’ I’m no soldier. But when I see Ken [Carpenter], dressed head to toe in the U.S. colors, it occurs to me that I can serve and honor my country by representing the United States at the Olympics.”

This, for me, is one of the curious things about Nothstein’s story (bearing in mind my somewhat skewed view of the Olympics). For sure, yes, there is a national pride thing going on with Nothstein, the lure of the Cold War’s five-ring circus is partly about doing Uncle Sam proud. But much of what seems to have driven Nothstein seems much closer to home. He’s more community focussed. The Olympics, when he says they were a way of serving and honouring his country, I get the feeling they were more a way of honouring his father and his father’s friends. Of honouring the community – the family and extended family – he grew up in.

The community thing comes back at the end of The Price of Gold, after the Sydney Olympics and after Nothstein’s stint on the European Six Day circuit and on the road in the States. In all his years Nothstein never left Lehigh Valley. Trexlertown was always his home. Post-retirement Nothstein went on to take over the vélodrome he learned his trade in, handing on to others that which had been handed on to him. And this is the hook for me in Nothstein’s picture of Lehigh Valley: it’s a living, breathing, real community. A cycling community:

The vélodrome [in Lehigh Valley] is my second home. The track served as my childhood playground; the lush, green infield grass, an immaculate front lawn; the concession stand, an always stocked pantry, an expansive living room seating my extended family – the fans.”

Nothstein was, largely, a product of his own drive and of the support structures that grew up around Lehigh Valley. Yes, he had the Fed’s sprint coach, Andrzej Bek, in his corner. But his personal coach was Gil Hatton, that guy who turned up in T-Town one day dust-covered and in a thrashed Plymouth. Not being a product of the U.S. Cycling Fed, Nothstein worked out his own training programmes. In preparing for the 2000 Games he looked at the time between Atlanta and Sydney as one big training block. Rather that gearing his schedule around World Cups or National and World Championships, everything was focused on Sydney:

I know this training plan will likely cost me dozens of World Cup wins, and probably a few world titles, but I don’t care. I train right through World Cup races without resting (in training lingo, tapering), so that I’m fresh for competition. Let my competitors rest and beat me now, I think. They’ll pay in Sydney. […] I’m cognizant of the risks of this training plan. If I don’t win gold in Sydney, I will surely regret the potential World Championship wins I gave up by not tapering.”

At a USOC training camp in Colorado Springs in early ’98, Nothstein watched a group of weight lifters playing basketball. The way the weightlifters burst off the ground to slam a basketball home amazed him:

I know the Olympic lifters are strong, but the explosiveness they display boggles my mind. It’s the same type of strength I use during a sprint, power combined with quickness. I need to know what they’re doing in the gym.”

Nothstein starts to incorporate Olympic weight lifting – clean and jerk – into his training programme. Later, in Lehigh Valley, he hooks up with a coach who’s studied the old Soviet way of training and who helps him hone his reaction time and work on his fast-twitch muscles by getting him running short sprints, sometimes held back by elasticated ropes, sometimes pulled by them. Today, these are the sort of innovative counter-intuitive training techniques you’d expect a national federation to be on the lookout for. For Nothstein, he had to find them himself.

Ok, isn’t it about time the D-word cropped up here? This is, after all, the height of Gen-EPO, these are the years BALCO was on the rise. Here, sadly, I have to offer the one big regret about The Price of Gold: the manner in which it which it skates over the doping issue leaves an awful lot to be desired. Nothstein manages to be blunt and forthright on a lot of other issues. On the issue of race fixing on the track he doesn’t try to hide the fact that it goes on. On doping, though, I really felt he could have done a better job.

Who was paying for all of this if Nothstein wasn’t being handsomely remunerated by his fed to bring home international pride in the form of Olympic bangles and baubles? EDS. Ross Perot’s little company had turned an employees’ cycling club into “perhaps the most talent-laden track cycling team in the world.” As well as funding a track team – for which Nothstein rode – EDS had invested heavily in a $4 million state-of-the-art vélodrome in Frisco in the suburbs of Dallas. They funded a nationwide series of track meets. And they were funding the U.S. Fed to tune of about a million dollars a year. As well as paying Nothstein to ride for their team, EDS also took Gil Hatton on board as coach.

Then one day in 1999, the cycling-loving CEO of EDS got the chop and his replacement took the axe to the sporting side of the company’s marketing operations. Bye bye the Superdrome and the EDS Cup. Bye bye Marty Nothstein and Gil Hatton. Bye bye USCF. Nothstein got lucky quick enough, AutoTrader.com picked him up, albeit on a much-reduced salary. I guess you know what happened with the USCF. (Later it was revealed that the guy who ran the cycling side of EDS, Nick Chenowth, was lining his own pocket: he got ordered to repay $1.3 million to the company, and then got more than two years in the big house.)

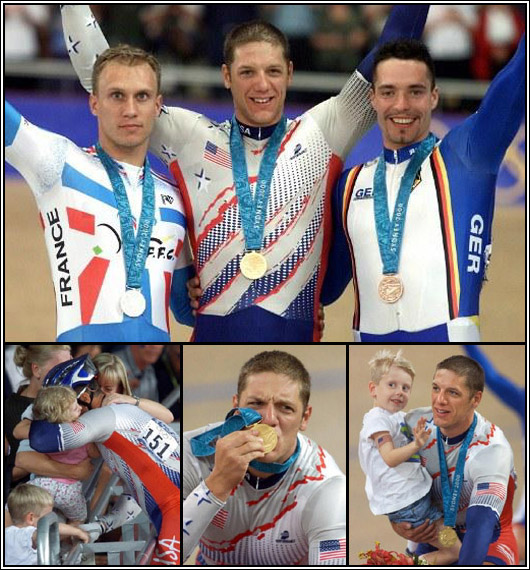

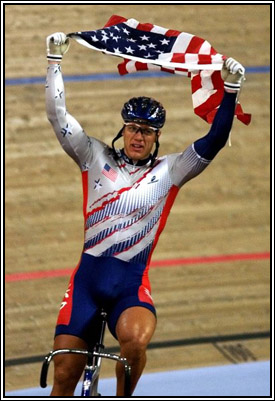

What it’s all about, Marty? Top: Nothstein on the podium in Sydney, flanked by Florian Rousseau and Jens Fiedler. Bottom: Nothstein with his wife Cindi, daughter Devon and son Tyler.

The price of gold can be measured in dollars. It can be measured by hours in the gym. But the real price is personal. With Nothstein, it’s not just the world titles foregone (and widening your focus here a moment, whether an over-emphasis on the Olympics diminishes World Championships). It’s the sacrifices he made on the home front. And the sacrifices his wife and children made on the home front.

After the medal ceremony, someone hands me an American flag. I ride another victory lap. I wave the flag above my head. Six thousand people stand and clap and cheer for me. But they’re cheering for me alone, and I didn’t win a gold medal by myself. I stop in front of my family again. I lift Tyler up like a lion carrying a cub.”

So, was it all a price worth paying? What do you think?

* * * * *

The Price of Gold, by Marty Nothstein (with Ian Dille), is published by Rodale Press (2012, 256 pages).

1 Comment

Having to use banned performance enhancing drugs to win is definitely not worth the price.