This piece originally appeared on irishpeloton.com on 3 April 2013

Earlier this year I had an online conversation with an editor of a popular cycling news website. The exchange involved the idea that journalist David Walsh should have his integrity questioned for not tackling the doping issue earlier in his career. The editor said the following: “David Walsh has done some fantastic journalism down the years, especially on Lance Armstrong. But [he] started covering cycling in 1979-1980. Why did he not pursue the drugs issue pre-Armstrong?” He continued, “the guy was part of the problem for 20 years. His integrity needs to be questioned. When it suited him to look away, he looked away. I know he has done great work, that’s not in dispute. But he pretty much ignored the drug issue for two decades. That needs to be said. It’s not about heroes and villains, it’s not black and white like that. And massive periods of Walsh’s career don’t stand up to scrutiny on the drugs issue”. And he concluded “we need to examine his full contribution, not just the years when he decided to man-up. Drugs in cycling have been very public since Tom Simpson died after using them in 1967. The Festina affair in 1998 came after years of massive drug taking in the peloton. Your refusal to even let someone else question Walsh is very curious. I think he cosied up to Kelly and Roche for years and squeezed the maximum out of them for his own career and decided not to rock the boat to keep everyone sweet. Then when they were gone and he didn’t really need access to riders any more because he was writing about other sports too, only then did he decide to tackle the story he’s been sitting on for 20 years” As the paragraph above suggests, I was in complete disagreement with him. The editor in question suggested I write an article underlining my argument, which is what follows. Walsh’s admission that he was complicit in his early years does not excuse him for it, but in my opinion, it was his actions in the proceeding years that rendered his prior neglect to be rather insignificant…

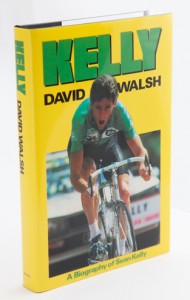

There aren’t many people who could have felt as vindicated as David Walsh did when the Reasoned Decision containing details of the doping practices of Lance Armstrong and his US Postal team was released last December. Finally, the truth had caught up with Armstrong and he eventually admitted to Oprah Winfrey in a televised interview that he had cheated to win all seven of his Tours de France and had been lying about it ever since. Having watched an unbelievable performance from Armstrong, climbing to victory in Sestriere on Stage Nine of the 1999 Tour, Walsh had spent many of the proceeding moments of his life pursuing this story when most others were happy to let it lie. He wrote two books, ‘L.A. Confidential’ and ‘From Lance to Landis’, which contained many of the details which have since been confirmed to be true by the Reasoned Decision. He has now written a new book called ‘Seven Deadly Sins’ which recounts his dogged pursuit of cycling’s most prominent cheat. But Walsh has been writing about cycling since the late 1970s. Why did he not pursue the drugs issue in the years between then and the Armstrong era? Did it suit him to ignore the tough questions and to use the success of Stephen Roche and Sean Kelly so that he could further his own career as a journalist? Was he actually part of the problem for 20 years? Of course, Walsh was not always a doping pariah. In a public appearance in February at The Pavilion in Dun Laoghaire at an event called ‘Whistleblowers’ where he sat with Paul Kimmage and was answering questions from Alan English, Walsh discussed his attitudes in his early years writing about cycling in the 1980s.

“I was born in Slieverue in County Kilkenny just 18 miles from Kelly’s home town of Carrick On Suir. I was a huge Sean Kelly fan at that time.”

At The Pavilion, the topic was raised of the 1984 edition of Paris-Brussels where Kelly tested positive for the banned substance Stimul and was handed a one month suspended sentence and a fine of one thousand Swiss Francs. Walsh wrote a book about Sean Kelly in 1986 and English asked Walsh to comment on the accusations that he glazed over the doping issue in that book.

“I didn’t glaze over it” said Walsh with a self-deprecating chuckle, “I completely ignored it. I didn’t want to contribute to the story that Kelly was doping.

“At that time, I still found a way of thinking to myself that if I interview guys and I ask about doping, I will not question their answers. I didn’t want to go there.”

When writing the book, simply titled Kelly, Walsh sought the opinions of Roche and Robert Millar about Kelly’s  positive test. Millar suggested that Stimul, as a drug of choice for cyclists, would have been absurd as it was ‘ten years out of date’. Roche said “How can they do this to Sean? He has been easily the best rider in the world this season and they accuse him of taking something in a race like Paris-Brussels. I know Sean well enough to know that it is nonsense”. The Irish Cycling Federation also seemed to think it was nonsense as the secretary at the time Karl McCarthy travelled over to Belgium from Cork to attempt to help in absolving Kelly of any wrong doing. Procedural irregularities were blamed in order to get Kelly off the hook. The UCI bought the excuse but they needed the Belgian cycling federation to agree in order to reverse the punishment. The Belgians refused and the fine and sentence were upheld. Walsh defended Kelly in his book. He suggested that because Stimul is a drug which always shows up in tests, surely Kelly would not have taken this drug for a relatively minor race like Paris-Brussels. At the time the top three finishers in a race were guaranteed to face the drug testers, Kelly finished third in that 1984 edition of Paris-Brussels, so Walsh also suggested that if Kelly had actually taken the drug that he would surely have made certain he did not finish in the top three. This twisted logic came at a naive time in Walsh’s career where he admits now that he was willing to ignore evidence which was right in front of him. He writes in ‘Seven Deadly Sins’:

positive test. Millar suggested that Stimul, as a drug of choice for cyclists, would have been absurd as it was ‘ten years out of date’. Roche said “How can they do this to Sean? He has been easily the best rider in the world this season and they accuse him of taking something in a race like Paris-Brussels. I know Sean well enough to know that it is nonsense”. The Irish Cycling Federation also seemed to think it was nonsense as the secretary at the time Karl McCarthy travelled over to Belgium from Cork to attempt to help in absolving Kelly of any wrong doing. Procedural irregularities were blamed in order to get Kelly off the hook. The UCI bought the excuse but they needed the Belgian cycling federation to agree in order to reverse the punishment. The Belgians refused and the fine and sentence were upheld. Walsh defended Kelly in his book. He suggested that because Stimul is a drug which always shows up in tests, surely Kelly would not have taken this drug for a relatively minor race like Paris-Brussels. At the time the top three finishers in a race were guaranteed to face the drug testers, Kelly finished third in that 1984 edition of Paris-Brussels, so Walsh also suggested that if Kelly had actually taken the drug that he would surely have made certain he did not finish in the top three. This twisted logic came at a naive time in Walsh’s career where he admits now that he was willing to ignore evidence which was right in front of him. He writes in ‘Seven Deadly Sins’:

“I tried to make the case that it was hard to believe Kelly had used a substance so easily detectable. I chose to see the ridiculous leniency of the authorities as proof that, at worst, it was a minor infraction. It wasn’t how a proper journalist would have reacted.”

At this point in the 1980s, Walsh had formed a friendship with Kimmage who was busy attempting to forge a professional career of his own. When Kimmage’s own book, ‘A Rough Ride’ was released in 1990 containing stories of doping in the professional peloton, much of it was not news to Walsh. But still, as Walsh admitted in The Pavilion back in February, he was willing to turn a blind eye.

“In the early 1990s, the allure of cycling was very much alive for me. I didn’t want to let go of the Tour de France as a dream. I still had a dream that I would write a Canterbury Tales type book about the Tour” [which he did – ‘Inside the Tour de France’].

Even though Walsh’s interest in the doping had already been piqued in 1988 when Pedro Delgado tested positive on his way to winning the Tour de France, it wasn’t until an incident in 1996, which took place outside the sport of cycling, which would see Walsh’s journalistic radar fully spin toward the direction of the cheats. Michelle Smith had just won four Olympic medals (three gold) for Ireland, swimming at the Atlanta games and stories began to emerge that she had doped in order to do so. Walsh was pursuing the story for the Sunday Tribune while Kimmage was also on the trail for the Sunday Independent. Walsh is careful to acknowledge the role of the sports editor when pursuing controversial stories. He remains grateful to his editors at the Sunday Tribune and Sunday Times who allowed him to pursue these topics when others may not have had the courage. He provides RTE as an example of a media outlet at the time that was unwilling to pursue the Michelle Smith story. An RTE sports reporter had spoken to Walsh about Smith and had decided that she also wanted to report the doping details. However when she approached her RTE sports editor, she was asked ‘do we really want to interfere with the national mood’?

It takes a certain kind of editor and a certain kind of journalist to decide ‘yes, let’s do it’. Walsh had, eventually, become that kind of journalist.

Not long afterward, the Festina affair erupted at the Tour de France and what had long been left unspoken in cycling was finally emerging. Instead of being buried in back pages and footnotes, doping was suddenly front page news. This gave even more credence to journalists who were willing to write about the difficult stories. What had previously been a taboo subject was now very much on the agenda. Finally, the 1999 Tour de France arrived and Walsh, hardened by the cynicism which had by now escaped from within and materialised, was ready to disbelieve and question what Armstrong was doing on those Alpine inclines. Walsh said in a recent interview with cyclingnews.com

“Maybe I was lucky that Armstrong came along in the right time in my journalistic life. If Armstrong had been there in 1984 would I have asked questions? Probably not.”

There are countless characters in the Armstrong soap opera that require their integrity be questioned. David Walsh is not one of them. To cast aspersions now on Walsh’s probity for not tackling doping in the 1980s is applying the standards of today to an era when the landscape of sports journalism was completely different. He admits that it took him time to see the light on doping, that he was a fan with a typewriter and that he was young and naive.

None of us are naive now, thanks to David Walsh.

No Comments