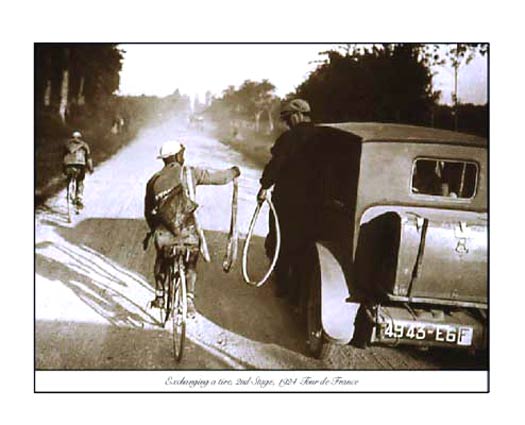

Our look at the 1924 cycling season continues with the second part of the Tour de France, in which Albert Londres has some fun with one of the true stars of pre-War French cycling, Alphonse Baugé.

As the Tour completed its first week of racing, the peloton completed the 412 kilometre stage four haul from Brest to Les Sables d’Olonne, sixteen and a half hours of saddle time. The peloton again finished together, Ottavio Bottecchia (Automoto) finished two places behind Théophile Beeckman (Griffon) but still retained the yellow jersey, the two still tied on time. Nicolas Frantz (Alcyon) finished outside the top ten and the third place was now a tie between Hector Tiberghien (Peugeot), Marcel Huot (Griffon), Giovanni Brunero (Legnano), and Léon Scieur, all still 2’36” behind Bottecchia and Beeckman.

Londres’ report from that day’s racing mainly concentrates on the quality of the roads the riders raced over, the journalist drawing particular attention to the amount of dust kicked up by the passage of the race. His report of the race into Les Sables d’Olonne could easily have been called Eat The Dust:

There are certain freaks who swallow bricks, others who eat live frogs. I’ve seen fakirs tucking into molten lead. These are normal people. The real nutters are certain lunatics who left Paris on 22 June to tuck into dust. I know them well: I’m a member of the club. We’ve scoffed 381 kilometres between Paris and Le Havre, 354 kilometres between Le Havre and Cherbourg, 405 kilometres from Cherbourg to Brest. It didn’t satisfy us. When you’ve got a taste for it, you can’t get enough. Even the waiter at the hotel in Brest, registering what an appetite we had, was sympathetic. An hour after midnight, he knocked on our bedroom door. ‘It’s 1 am,’ he called. ‘Time to eat your dust.'”

Londres’ reporting generally displays a sense of the ridiculous, humour used gently to press home his points. Here he is comparing the quality of the dust in the different départements the race crossed:

We crossed Finistère and on through the départements of the Morbihan, the Lower Loire and the Vendée. The dust of the Morbihan is poor stuff compared to Finistère’s and the Lower Loire dust is a bit more tangy. As to the Vendée dust, it’s a real delicacy. I only have to think about it and my mouth waters. I just hope that the dust in Landes – next Monday – is as good.”

At Landernau, which the peloton whizzed through in the dead of night, Londres noted the silence of their passage:

It’s the only town since the start where there’s no noise to be heard. It’s 2.30 in the morning, Landerneau is asleep. It’s cold. Châteaulin is asleep. The wheels of 100 bicycles crunch over the ground.”

By Quimper, though, the crowds were once again out to greet the passage of the men of the Tour. Londres used a comment from a local to draw attention to the poor pay earned by the racers, a theme he would soon be returning to:

One Breton, thrilled by the sight of them, said: ‘It’s sad. We lay out 250,000 francs on a horse for a 2 ½ minute race and men who work a lot harder than any horse get chicken feed.'”

While much of Londres’ reporting can correctly be classed as colour, painting the broad picture around the race more so than the picture of the race itself, he does occasionally comment on some of the racing action:

We pass a wild beast at the side of the road, ferociously devouring rubber. It’s the maillot jaune, Bottecchia. He’s punctured. To get the tyre off more quickly he’s tearing at it with his bare teeth. [Peugeot’s Romain] Bellenger remounts after puncturing. He calls out as he goes past: ‘They’re blowing it apart at the front.’ It’s [Peugeot’s Philippe] Thys shaking things up. He escapes with two accomplices. Frantz and [Jean] Archelais riding elbow to elbow. A touch of drama. Frantz has been instructed to keep the tempo high. I don’t really know why Archelais is here. He’s a shadow man [a touriste routier], a rider without a stable, riding for himself since the start, no manager, no thighs, no calves, no nothing. At the finish of each stage he’s in such distress he weeps like a child, but he’s always in at the finish with the ‘aces.’ You feel like giving him a push on the bike, whereas Frantz is brutally strong. If Frantz dared to say ‘I’m tired’ the telegraph wires by the road would convulse with laughter. Result? We wouldn’t be able to telegraph our reports through from Brest to Nantes.”

The next day’s racing, the fifth stage and the second Monday of the Tour, saw the peloton riding a mammoth 482 kilometres from Les Sables d’Olonne to Bayonne, more than nineteen hours in the saddle. Omer Huyse (Lapize) slipped away from the peloton, taking the stage with an advantage of 1’11” over the group behind, which was led home by Bottecchia. Beeckman, who had started the day second overall, slipped down the rankings. Hector Tiberghien (Peugeot) and Giovanni Brunero were now in second, tied on time. For the Legnano rider, Brunero, this was a bonus, he having been one of the riders to miss the Giro earlier in the year, either in the dispute over appearance fees or to save himself for the Tour, choose for yourself whichever you think the more likely. A good ride in France would more than make up for shunning his home Tour.

The 1924 Tour entered the Pyrénées on Wednesday July 2nd. A 326 kilometre haul from Bayonne to Luchon, taking in the Col d’Aubisque (1,709m), the Col du Tourmalet (2,115m), the Col d’Aspin (1,489m), and the Col de Peyresourde (1,569m). It was here that Bottecchia put his rivals to the sword and won the Tour de France. The Italian ace led the race over all four climbs and arrived into Luchon 18’58” ahead of his Automoto team-mate Lucien Buysse bagging another three minutes in bonifications to cushion his lead. Buysse leaped up to second overall in the race, 30’21” down on his team-mate. Third in GC, 42’185″ behind Bottecchia, was Nicolas Frantz, who finished the stage in fourth, two minutes behind his Alcyon team-mate Louis Mottiat and 35’34” behind Bottecchia.

The next day’s racing, Friday, saw the Tour tackle another four Pyrénean climbs: the Col des Ares (797m), the Portet d’Aspet (1,069m), the Col de Port (1,249m), and the Puymorens (1,915m). Buysse led the race over the Ares, Beeckman over the Portet d’Aspet, Bottecchia and Arsène Alancourt (Armor) crossed the Port together, while Thys led over the last of the Pyrénean summits, the Puymorens. Racing into Perpignan, 323 kilometres after leaving Luchon behind them, Bottecchia, Thys, and Alancourt were 3’48” clear of a group of five, Bottecchia taking his third stage on the Tour and another three minutes in bonifications. Frantz, who finished first in that chasing group of five, moved up to second overall, with the third place now held by Marcel Huot, 55’54” behind Bottecchia. Bottecchia’s team-mate, Buysse, who’d started the day second and led the race over the first climb, finished more than half an hour down on the day. Exiting the Pyrénées, only 20 of the 46 first class riders were left in the Tour.

With now two weeks of racing under their wheels the peloton started into week three of the race, Sunday’s stage eight serving up a testing 427 kilometres from Perpignan to Toulon. Alcyon’s Louis Mottiat led the race home on his own, 2’25” ahead of Giovanni Brunero and 4’21” ahead of Bottecchia. The Italian Automoto rider now had a 50’56” lead over Frantz, with Brunero taking third place on GC, 58’32 behind his compatriot.

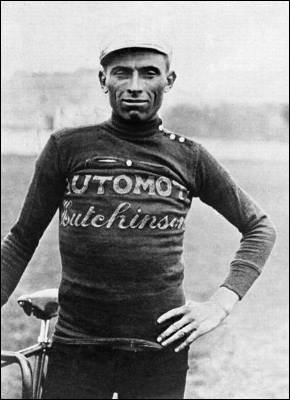

At Toulon, the Pyrénées behind the peloton, Londres’ report concentrated on the role of Alphonse Baugé, the directeur sportif of La Sportive:

“The Marshal is Alphonse Baugé. He is commander in chief of racing cyclists … those of the Tour de France, those of the Six Days, those of the classics, road-riders and track cyclists. Alphonse Baugé leads French cycling. He is the only man who, nowadays, I think is capable of accomplishing a miracle. He could mount a boy on a bicycle that had neither saddle nor handlebars! Alphonse Baugé will one day be canonized!

“His uniform is dark blue and cut in the form pyjamas, a red woollen braid borders the jacket. Baugé is particularly recognizable by his toothy smile, like the actor Mistinguett. He follows the race in a closed car, and it s not just the car that is closed, but also his mouth.

“At the départ the secretary general secretary of the event sows shut his lips with brass wire. The other day, out of pity, I wanted to push a straw into the corner of his mouth and send him some air; he refused to let me do this: he’s a stickler for the regulations.

“At the arrivée, the secretary general takes from his pocket a pair of shears and cuts the brass wires. Then Baugé breathes three times, finds that his heart is still beating, pauses for thought and then seeks out the hotel of the riders.”

Good knock-about stuff from Londres there, a fun caricature of one of the true characters of French cycling. Londres here is, in some ways, using Baugé as a stand-in for Henri Desgrange, or the way cycling is run in general. Like Desgrange Baugé epitomised the authoritarian nature of the Tour and cycling in general. A former rider himself – he was French amateur national champion in 1896, the year of Teddy Hale’s win in the Madison Square Garden Six – Baugé covered the 1903 Tour as a journalist for L’Auto-Vélo‘s great rival, Le Vélo. When François Faber won the Tour in 1912 and 1914 for Peugeot it was with Baugé as his directeur sportif.

Londres then reports an exchange of words he’d witnessed in Brest, at the end of the third stage. Baugé is talking to one of the riders, Joseph Curtel, who wanted to abandon the race, having only earned 650 francs in 1,200 kilometres of racing:

– So it does not bother you, whether you sing at the Operá or at the Batignolles? [a music hall in Montmartre]?

– In [a race at] Marseilles, I got 5,000 francs for 300 kilometres.

– So, no, you’re not a great artist you only see yourself as a provincial baritone who plays comic scenes?

– Hey! I prefer a hundred francs at the Batignolles to pennies at the Opéra!

– So you have no pride? You have not even that? You do not think about the pride your elderly parents have in your?

– Hey! My parents are not that old …

– You do not want to know, your mind is closed. Here, I’ll take an example, you know Kubelik, the great violinist? Good! Do you think Kubelik would stop playing the violin if he got only 650 francs? No! Kubelik is an artist. Well! You too are an artist, an artist of the pedal. For the first time, you have the honour of riding the Tour de France, the beacon of cycling, and because of some story about 650 francs, you would let that go?

– If I’m dying for 650 francs, how am I going to earn a living?

– Well then, you’re just a labourer, a bungler of plaster, a bootblack, a dish washer. You do not understand the beauty of the handlebar. Do what you want … You disgust me …

A later exchange, from the fifth stage, the race readying itself for its assault on the Pyrénées, is next reported. Another rider was preparing to abandon when Baugé chimed in with his patented pep talk:

– You’re going to abandon, you who have a system for the Pyrénées?

– But I have no system for the Pyrénées, Mr. Baugé!

– Yes you do have a system for the Pyrénées. You will abandon, you who everyone is expecting on the cols.

– No, Mr Baugé, nobody is waiting for me on the cols.

– Everyone is waiting for you, I tell you, you know that as well as I do, you whose ancient Pyrenean grandmother will offer you flowers at the summit of the Tourmalet!

– I don’t give a fuck for flowers, Mr. Baugé! I tell you I have no tendons.

– It’s not about the tendons.

– With what will I push then?

– Go to your masseur, he’ll make tendons for you. Listen, my boy, have you heart?

– Yes, but I have no tendons.

– Do not think about that, think about your success, your name in the big newspapers of Paris, the band who will welcome you at the station when you return home if you finish the Tour.

– But, good Lord, Mr Baugé, I tell you …

– Yes, you tell me that you have no tendons … that is understood … Well then! Become an undertaker and not a racing cyclist, you hear me, farewell!

And then in Luchon, after the first stage in the Pyrénées, Londres had witnessed yet another exchange of words between Baugé and a group of riders. The riders this time are questioning whether cycling is any kind of trade, when Baugé chips in:

– Do you believe it’s a trade?

– It’s not a trade, it’s a mission.

– [Henri Collé] Our mission is to be with our wives, and not to work like slaves rowing a galley.

– Your wife is your bicycle.

Hector Tiberghien, the playboy of the peloton, interrupted Baugé to say that bikes and women had nothing in common but Baugé was in full flow, banging on:

– If it’s a trade, what a great trade! In what other trade would the whole of France spend a month crying out ‘Alavoine! Thys! Sellier! Mottiat! Bellenger! Jacquinot!’ and so on?

– [Alavoine] When you’re puking your guts up that’s not going to make you stronger.

– Here, take Bottecchia; do you suppose that, if Rockefeller had offered him fifty big ones at the top of the Tourmalet, Bottecchia would have quit? No. Because Bottecchia has an ideal.

– Yes, to buy land in his native Italy to build a house, since he is a mason, and plant his spaghetti …

– But no …

– [Bottecchia] Yes, yes, it is so.

In Perpignan at the end of the following stage Baugé had commiserated with Robert Jacquinot (JB Louvet) and Félix Sellier (Alcyon), who had quit the race, complaining it was too tough:

– I understand that, my children, but know that there are no great riders without great suffering.

In Toulon the riders were complaining about crashes, particularly riders being taken down by cars following the race, when Baugé chipped in:

– My friends, I too have fallen, I too have been knocked down by cars. I am a child of the game, I know what it is. There are wooden cross in our business as in others. Do you know what I would do? I would read Duhmael’s Lives of the Martyrs. After that, you’ll have the courage for tomorrow’s stage. It is I who tells you this.

– It is found in Toulon?

– It is found everywhere

– Well, we will buy it then …

* * * * *

From Toulon the peloton had 280 kilometres to cover before getting to the Côte d’Azur and finish of stage nine, in Nice. One of the stories of that stage concerns one of the shadow men, a touriste routier by the name of Jules Banino, a fifty-one-year-old policeman from Nice who, it is said, rode the Tour during his vacations. Roger Dries, in Le Tour de France de Chez Nous, offers this picture of Banino:

You saw him in all the sports events ever organised. There was a swimming meeting? He’d be the first to turn up, perched on his bike, and he’d dive into the sea and take part. A pole-climbing contest? Banino would be there. He once even took on the same wager as the Count of Monte Cristo, tying himself in a sack and being thrown into the Mediterranean, at Tabau-Capeu. He nearly drowned. He had to be pulled out in a hurry and was hardly breathing when they got to him.”

On the ride into Toulon, Banino – it’s reported – had been caught by the cut off and forced to leave the race. He decided to make the most of the rest day before setting off home for Nice. Banino just happened to set out for home an hour or two ahead of the peloton.

At some point after the stage got underway word reached the peloton that, somehow, a rider was ahead of them. The pace was ratcheted up and soon enough the headlights of the cars leading the way were illuminating the figure of a cyclist ahead. The peloton couldn’t work out what was going on, everyone was either present or accounted for: who was this rider up the road ahead of them? They chased hard to close in on Banino. When they finally closed in on him they demanded to know who he was and how’d he’d slipped ahead of them.

Banino gave them his story: that he was a touriste routier who was out of the race and just happened to be riding home along the same roads as the Tour. The stars were less than pleased with Banino’s story and the energy he’d caused them to waste. Bottecchia – it’s claimed – landed a thump on him. And then a few more. Other riders joined in the melee, including Peugeot’s Jean Alavoine. Alas for Banino, some fans of Alavoine were nearby and – without understanding what was really going on – decided their man must have been attacked and was simply defending himself. Acting first and thinking later, they leapt to his defence, joining in on the assault on Banino, beating him with sticks. (The fanaticism of some fans hasn’t changed down through years, though today they’re slow to reach for sticks and stones in defence of their idols. Tossing names at those who pick on their heroes is the best they can manage. Thank God.)

That’s the accepted version of the story of what happened on the road from Toulon to Nice, as it appears in various Tour texts. How true is it? For a copper, Banino seems to have been slow to press charges against those who assaulted in him. Certainly in the standard stories of Bottecchia’s life there’s no mention of the incident. And there’s one very big problem with this story: while Jules Banino did start the 1924 Tour de France, he was a DNF on the first stage. But this is what happens in cycling: stories get added to the legend, get repeated, become fact. And when the legend becomes true – such and such is the most tested rider in the peloton, such and such is the most successful directeur of all time – it is the legend that gets printed. Only sometimes do we bother to stop and check the legend against the facts.

Whatever really happened on the roads between Toulon and Nice in July 1924, Thys and Bartolomeo Aymo (Legnano) slipped away from the peloton to finish first and second, Thys taking the stage and the bonifications. Six minutes behind them Alavoine led home Bottecchia, Brunero and Frantz, leaving the GC unchanged.

The Tour took another rest day as the riders gathered their breath before their assault on the Alps. In the previous year’s Tour Bottecchia had seemed to climb effortlessly until he came to the Col d’Izoard and its Casse Déserte. Would that again be the site of his downfall or was the Italian set to make history and become the first Italian to win the Tour de France?

1 Comment

[…] The 1924 Tour continues. Tags: 1924, Albert Londres, Henri Pelissier, Tour de France function fbs_click() […]