In part two of our ongoing series addressing some of the key issues in the revenue-sharing debate, we consider the next phase in the history of one of that argument’s key-players: the Amaury family. In this episode we sprint quickly through the second half century of the Tour’s history and consider how the Amaury dynasty coped with the handover to the next generation of the family empire.

Having talked his way into co-ownership of the Tour de France in 1947, Émilien Amaury put one of his own men inside the Tour to watch over his interests. That man was Félix Lévitan, the editor of Le Parisien Libéré‘s sports pages.

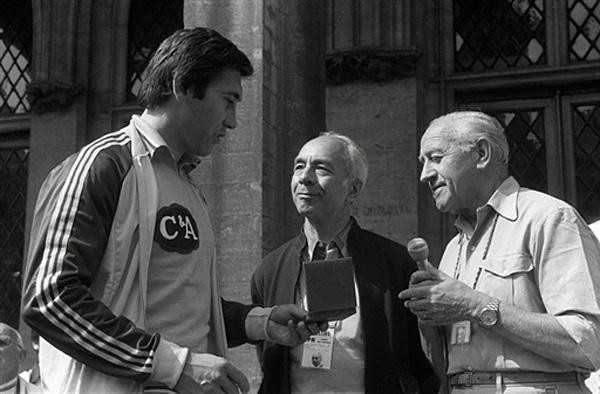

Eddy Merckx talks with TdF race organisers Lévitan and Goddet Photo: © AFP Photo courtesy of CyclingNews.com

The Tour’s Godfather

Félix Lévitan had begun his working life at the magazine, La Pédale, in the late thirties before taking up a position with L’Auto. During the war, amid the various round-ups of Jews, he was interned first in a military camp in Paris, then later in Dijon. After the Libération, Amaury appointed him as head of sport at the newly launched Le Parisien Libéré.

Amaury charged Lévitan with turning the Tour into a business and not just a circulation-boosting stunt. Given that L’Équipe and Le Parisien Libéré were not the only ones whose circulation got a boost from the Tour, this was the sensible thing to do. Lévitan’s role in the development of the Tour into a self-sufficient commercial enterprise was vital. “The Tour would not have become what it is today without Lévitan,” claimed Hein Verbruggen. “He developed the sponsorship agreements with the host towns and realized the economic potential offered by television.”

In 1962, Lévitan officially became co-director of the Tour, Goddet ceding a share of the limelight. In 1975 Lévitan was the instigator of two major changes to the Tour: the introduction of polka-dot jersey for the best climber and switching the finale of the race to the Champs-Élysées.

That same year, Émilien Amaury was showing how much of a hard-nosed businessman he really could be. With Le Parisien Libéré‘s circulation in decline in the early seventies, in 1975 he set about firing several hundred staff. Most of them were printers. If you know anything about the newspaper industry the world over you will know the power of the print unions and the manner in which they wield it. Amaury’s cut-backs led to a lengthy and vicious dispute with the sacked printers, which lasted for more than two years. During this time Amaury was able to continue printing and distributing Le Parisien Libéré, using workers from the socialist Force Ouvrière union instead of the communist Fédération du Livre.

The dispute led to protests at the Tour de France, but pointing that out seems a little self-centred when you consider what else happened during the strike. An attempt was made on the life of Le Parisien Libéré‘s editor, Bernard Cabanes, in the form of a bomb outside his home. But the people who planted the explosives picked the wrong Bernard Cabanes and murdered instead the editor in chief of Agence France Presse, who happened to have the same name. André Bergeron, the leader of the socialist print union whose workers were helping Amaury break the strike, was injured in a second attack that same night.

Émilien Amaury died in 1977, aged 67, after falling from his horse and before the dispute with the printers was settled. Peace was finally achieved in the late Summer of 1977 – in the interregnum between the death of Amaury and the arrival of his heir – when the striking workers were given jobs at the Nouvelles Messageries de la Presse Parisienne (NMPP, now Presstalis), the company which distributes newspapers in the Île-de-France area. The NMPP was half owned by the French publishing house Hachette, with the member journals owning the rest of the shares. In effect, the salaries of Amaury’s surplus printers were taken up by his rivals. The cost to Le Parisien, though, was not cheap: before the dispute it had enjoyed sales of more than 700,000 copies daily. Afterwards, that figure dropped to 350,000.

The Step-Father of the Tour

It was just as well that no one waited for arrival of Amaury’s heir before settling the dispute with the printers, for the death of Émilien Amaury was followed by a long battle for control of his empire between his daughter, Francine, and his son, Philippe. The daughter was the preferred successor, the son being overlooked by his father. Finally in 1983, after six years of legal battling, an amicable arrangement was reached. It saw the daughter taking control of the group’s weekly titles – Marie-France and Point de Vu Images Du Monde – with the son retaining the dailies. And, through them, control of the Tour de France. What happened to the Tour in the eighties was his handiwork.

Before coming to that, though, it is worth first looking at what happened at Le Parisien Libéré under its new owner. Working with Martin Desprez and Jean-Pierre Courcol – two of his colleagues from the marketing agency Havas – Philippe Amaury radically altered the editorial line of the newspaper his father had created. Under Émilien Amaury the paper had been, not unlike many tabloids, xenophobic and chauvinistic. Philippe Amaury put in place a new editorial directive and the paper became softer, less radical. In 1986, the title changed to Le Parisien. In 1994 – in response to the introduction of InfoMatin – Amaury launched a national edition of the paper, Aujourd’hui en France. The combined sales of the two titles make Le Parisien-Aujourd’hui en France France’s most popular daily newspaper.

Philippe Amaury’s legal battle to secure his inheritance did not come cheap. At the end of it, not only did he have a large legal bill to pay, he also had a not-insubstantial bill for death duties on his share of his father’s estate. And, after its long union dispute, the Group was not exactly flush with cash. To raise funds, Amaury sold 25% of his shareholding in the media group he had just fought so hard to inherit. The initial buyer was the publishing house Hachette, then headed by the Gaullist Jean-Luc Lagardère. Today, those shares are owned by Lagardère Active, part of Arnaud Lagardère’s media to munitions empire.

The Tour itself initially saw no impact from the change in ownership of its parent papers. That changed in 1987, when Félix Lévitan came unstuck, caught breaking a cardinal rule of business: he lost money. Worse, he’d buried the loss in the Tour’s books. The basic story of what happened is straightforward enough: Lévitan had dreamed of organising a Tour in America for several years. In 1980 he had punted the notion of a Tour of Florida. The next year he had the crazy dream of a Tour of California. Then the company responsible for selling the Tour’s TV rights in the States – Broadcast Rights International Corp (BRIC) – came up with the idea of a Tour of America, a three-stage race from Virginia to Washington, to be held in 1983. Lévitan was brought on board as an adviser.

Unfortunately, for all concerned, BRIC’s race ended up losing money. A not insubstantial sum of money. Lévitan – bless his cotton socks and kind intentions – decided to subsidise BRIC’s losses. To the tune of $500,000. Without consulting his bosses. This being the case, he couldn’t just write BRIC a cheque for half a million dollars. So he engaged in a little creative accounting. It was hardly the most clever accounting fraud I’ve ever seen, but it was – until it was discovered – effective. We’ll go into in more detail in a future part of this series of articles.

Lévitan’s little financial irregularity was discovered in the Spring of 1987 and he was unceremoniously booted out. He turned up for work one morning to find his offices locked. After that he went into a long sulk and didn’t even turn up at the Tour again until 1998.

The period between Spring 1987 and Autumn 1988 – the eighteen months following the ouster of Lévitan – was one of the rockiest in the Tour’s long history from an organisational point of view, with three different men taking charge of the race in the space of a year and a half.

The first of these was Jean-François Naquet-Radiguet, a 47-year-old businessman with a Harvard MBA, formerly the manager of the Cognac company, Martel, and their Latin American interests. In 1963, while a young Turk with 3M, he had followed the sticky-tape company’s cars in the Tour’s tacky publicity caravan. That was, more or less, his sole previous connection with the race. He was a total outsider.

Naquet-Radiguet managed to upset a lot of people with reforms he planned for the Tour. The who and the how isn’t clear, all that is clear is that a month before the start of the 1988 Tour – just twelve months into his reign – Naquet-Radiguet departed the scene. Jean-Pierre Courcol – who had helped Philippe Amaury change the editorial line at Le Parisien Libéré and was by then an editor with L’Équipe – was parachuted in to take over from him. He only lasted through to the Autumn of that year, choosing to stand down after becoming disillusioned by the mess of the Delgado affaire. Courcol was replaced by Jean-Marie Leblanc, whose tenure lasted through to the new millennium.

Out of those three men, Courcol is the one we want to pay attention to next. Unlike Naquet-Radiguet, Courcol stayed within the Amaury Group after standing down as director of the Tour, and became instrumental in the next step in the Group’s evolution. It was Courcol who introduced the idea of the Tour being the jewel in the crown of a sport events company. Thus was ASO born in 1992. ASO inherited L’Équipe‘s existing events – which included Paris-Roubaix and the Tour de l’Avenir – and added new events.

At this point Jean-Claude Killy was brought on board. A former skier – triple Olympic champion in 1968 – Killy had successfully turned his sporting fame to his financial advantage. He retired from sport at the age of 25 and became a client of Mark McCormack’s global sports marketing agency, International Marketing Group (IMG). With IMG’s help he became a star of Madison Avenue, ‘loaning’ his name and image to clients like Canon, Chevrolet, General Motors, Moët et Chandon, Rolex, Schwinn and United Airlines. By the time he joined ASO his personal wealth was estimated at 120 million French francs. As co-chair of the Organizing Committee of the Olympic Games in Albertville in 1992 (think, perhaps, Seb Coe, only with sex appeal), he had a Rolodex to die for. Philippe Amaury wasn’t quite ready to die for it, but he was willing to pay for it, generously.

With the aid of Alain Krzentowski, Killy took the Tour by the scruff of the neck and shook it. In just seven years ASO went from being worth 30 million francs to 60 million. Killy, though, refused to share the spoils of war. Growth of the Tour’s prize fund lagged behind, going from 10 million francs in 1992 to 15 million in 1999. By the end of the nineties, though, the good times seemed to be running out.

Among the various probable and improbable excuses offered for the eruption of the Festina affaire in 1998 is the role of Philippe Amaury and the Amaury Group. One version has it that Amaury’s public support for Jacques Chirac set opposing political factions against him. Thus, it is claimed, the Communist Party sports minister, Marie George Buffet, gladly seized on the opportunity to muddy Amaury’s face when it presented itself. Alternatively, it is also claimed Buffet was driven by the conflicts between Amaury’s press group and print unions, the latter being supported by the Communist Party.

One man who was not responsible for the Festina affaire was Killy. In fact, while much of it was unfolding, he was in the States, attending a Coca-Cola board meeting in Atlanta. When he did express a view on the events unfolding at the Tour, he dismissed the whole thing as being minor and of no great consequence. Coca-Cola – who had entered into a twelve-year sponsorship contract with the Tour in the mid-eighties and extended that annually when it ran out – didn’t quite agree with Killy and decided that, in the wake of Festina, they would immediately reduce their financial involvement with the race by 80%.

In 2000, Philippe Amaury felt that Killy and co had grown too powerful within the Group. An amicable parting of the ways was agreed. Killy departed ASO with a golden parachute of 50 million francs (circa €7.6 million). Krzentowski left with him, trousering 32 million francs (circa €4.9 million).

The year 2000 also saw Amaury extend his Group’s interests in another direction, paying €42 million to purchase the Futuroscope theme park, situated near Poitiers and which has hosted the Tour on a number of occasions since its opening in 1987. Within two years of having invested in it – having already lost a small fortune on the project – Amaury cut his losses and ran. In the Autumn of 2002, he sold the majority of his share-holding (the minority stake he retained was finally sold in 2006). For the princely sum of €18.5 million local representatives took the theme-park off Amaury’s hands.

The €23.5 million capital loss – plus an estimated €12 million in operating losses – kind of puts Félix Lévitan’s American troubles into perspective. And, as with Lévitan, a head had to roll. Jean-Pierre Courcol – whose bright idea the Futuroscope investment had been – was shown the door. Nearly two decades of loyal service to Philippe Amaury meant nothing when set against such a financial cock-up.

Perhaps Courcol’s biggest fault, in the end, had been a sense of invincibility which drove him to take an aggressive approach to problem solving. Between imitating Amaury’s catastrophic investment in Futuroscope and the Group’s eventual withdrawal from the ailing themepark, Courcol turned his attention to the NMPP. Courcol decided to orchestrate Le Parisien‘s withdrawal from the newspaper distribution entity, cutting the paper’s links with the troublesome print workers who had gotten jobs there following the union dispute of 1975-77. The short-term pain of another dispute with the Fédération du Livre, Courcol argued, would be offset by gains in the paper’s circulation. Those gains never materialised and, to many observers, Courcol looked like he was merely settling an old score.

If anyone thought that the aggressiveness of Amaury executives would be curbed by the dismissal of Courcol they had a rude awakening when the man who was appointed in 2000 to lead ASO into the new millennium declared war with the UCI over the latter’s attempt to impose the Pro Tour on the cycling calendar. It was a war that had been brewing since Félix Lévitan first argued with Hein Verbruggen over the introduction of the World Cup in the eighties. Under the leadership of Patrice Clerc, ASO and the UCI faced off in a dispute that would push cycling to the brink of destruction, with ASO threatening secession and the UCI trying to bring down the Tour.

In 2006, with the Pro Tour Wars dragging on, Philippe Amaury died of cancer at age sixty-six. Unlike the tussle for succession that followed the death of his father, there was a smooth transition after Philippe Amaury’s death: his widow, Marie-Odile Amaury took the helm of the Amaury Group.

Next: The widow Amaury: the Tour’s wicked step-mother?

Previously: The Man Who Sold The Tour.

3 Comments

FMK, bravo.

That is journalism.

luc

[…] The Rise of the Amaurys. Tags: Alain Krzentowski, Amaury Sport Organisation, ASO, Marie-Odile Amaury, Pat McQuaid, UCI […]

[…] The rise to power of a cycling dynasty. Tags: Emilien Amaury, Henri Desgrange, Jacques Goddet, Tour de France function fbs_click() […]