What are you looking for when you buy a cycling book? For the most part, cycling books deliver facts, some more coldly than others. By and large they tend to be somewhat utilitarian, you read them for the stories they tell, more so than for the way the story is told. A few authors do stand above the crowd and serve up books that are worth reading for the way the story is told as much as the story itself.

What are you looking for when you buy a cycling book? For the most part, cycling books deliver facts, some more coldly than others. By and large they tend to be somewhat utilitarian, you read them for the stories they tell, more so than for the way the story is told. A few authors do stand above the crowd and serve up books that are worth reading for the way the story is told as much as the story itself.

Paul Fournel is very much of this later order, that rare breed: a cycling author who serves up something you can actually enjoy reading. That something isn’t a how-to manual or techs-mechs porn. It isn’t about heroes or villains, biography or autobiography. It isn’t about roads or races. It’s neither novel nor poem. What it is is Vélo and the story it tells is a mix of all the things that it isn’t.

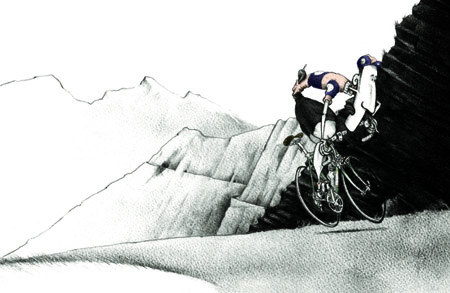

The essays that make up Vélo have gone through an interesting publishing history. They first appeared in Fournel’s native France in 2001 as Besoin de Vélo. In 2003 they got a North American publication when Allan Stoekl translated most of Besoin de Vélo – leaving out Sur le Tour de France 1996, seventy-five pages about following the 1996 Tour – and published them as Need For The Bike (University of Nebraska Press). In the UK, after Rouleur magazine appeared on the scene six years back, the essays began to be serialised there, with translation tweaks from Claire Road. Fournel began to add new essays to Rouleur, translated by Graeme Fife, and the two – the fifty-five essays that appeared in Besoin de Vélo and Need for the Bike plus the more recent Rouleur essays – are now collected in Vélo. As well as the essays themselves, Vélo serves up Jo Burt’s illustrations which accompanied the essays in their Rouleur appearances.

Martin Ryle in a recent essay – Vélorutionary, collected in The Bicycle Reader – has criticised Fournel’s essays by saying this of them:

A dispiritingly ‘hard’ ethos of competition as much as conviviality, and speed rather than ambling […] is also present in Paul Fournel’s Need for the Bike, many of whose sketches celebrate the pains and rewards of close-to-the-limit physical exertion, in a virtually all-male French subculture whose unquestioned heroes are the coureurs of the gruelling long-distance stage-races. Fournel is associated with Oulipo, the French avant-garde writers’ collective whose best-known member was Georges Perec. Reading Need for the Bike, I thought of Perec’s W, in which obsessional and ruthless athletic competition is the basis of a fascistic social order; and then I thought of the Olympic Velodrome in London. Here is the bike as fetishised speed-machine, not the antithesis but the very sign of turbo-culture’s conquest of mind and body: flesh is imagined as steel, rather than vice versa. For every potential cyclist who might be encouraged onto the roads by such images, a dozen must be put off.”

Paul Fournel as a champion of a fetishised turbo-culture? Let’s try this excerpt and see what you think of that:

The speed of a cyclist forces you to select what you see, to reconstruct what you sense. In this way you get to the essential. It’s the title of a book or a cover which your gaze brushes against, it’s a newspaper which catches your eye, a potential gift in a shop window, a new bread at the baker’s. That speed is the right one for my gaze. It’s a writer’s speed, a speed that filters and does a preliminary selection.

Or try this:

For me, road maps are dream machines. I like to read them as one reads adventures stories. As a driver, I use them to find the shortest route, to find the long roads which join towns without going through the countryside. As a cyclist I use them for everything else. If I know the area, every centimetre of the map is a landscape laid out before me. If I don’t know it yet, every centimetre is an imagined landscape that I will explore. For example, I like maps of Brittany, which is cycling country where I’ve never ridden. It’s my storeroom, my wine cellar. It’s the masterpiece that you have in your library and which you still haven’t read.

Paul Fournel as a champion of a fetishised turbo-culture? Bollocks to that.

Paul Fournel as a champion of a fetishised turbo-culture? Bollocks to that.

What Fournel’s essays really are is an exercise in mapping the geography of cycling. Geography is not just limited to the physical world and Fournel’s explorations encompass the whole landscape of cycling: from the outer world of roads travelled to the inner world the cyclist’s mind. And, like the road maps Fournel reads, the essays collected in Vélo are dream machines, transporting the reader into his or her own inner world of cycling. This is the real joy of Fournel’s essays: from the particular of his own cycling experiences Fournel is exploring universal truths which readers can relate to through their own cycling experiences. If, for every reader who finds truth and beauty in Fournel’s essays, a dozen are put off cycling by them then those dozen are no loss, for they can only be soulless, heartless creatures.

That Fournel’s essays are dream machines makes Vélo something of a oddity: a book you can claim you kept putting down and mean as praise. An example for you. Here’s Fournel talking about wind:

The strongest wind that I can remember having faced is the wind of the extreme west of Ireland. I pedalled along the coast, somewhere south of Galway, and I saw to it that I always set off riding against the wind to be sure that I could get back. I was alone, and it was a bitter flight. There was no forgiveness. All the things that can, elsewhere, allow you to cheat and to shelter yourself are not welcome here: no tress, no houses, no hedges, no hills. Nothing but the ocean wind – wet, powerful, inexhaustible. Flat out on my bike, I had the feeling I was going dead slow, condemned to using the gears of high mountains on a road that was flat.

Reading that, you effortlessly empathise with Fournel as you recall your own experiences with the wind. For me, I remember an Easter away, trying to get from Enniskillen to Killybegs and being blown to a virtual standstill as we crossed the Pettigo Plateau. Even the wheel in front seemed to provide no shelter. By the time we made it into Donegal – half as far again still to go – the thought of suffering more into that wind blowing in off the Atlantic was too much and we just stayed where we were. If, back then, I’d known about Costante Giradengo and the 1921 Giro, I’d have scuffed a line in the road with the toe of my shoe and said no further.

It isn’t always empathy that made me put Vélo down and slip off into memory. In 2000 Fournel was appointed France’s cultural attaché to Cairo:

In Cairo – where I’ve written some of these pages – I’ve had, after forty-five years of continuous cycling, my first experience of cycling severance. I just couldn’t see where I could slip a bike into this city, nor do I see – between the overburdened valley of the Nile and the deserted desert tracks – any shady countryside I could explore. […] So I’m biding my time. My bike’s wrapped up in the cellar in Paris, ready to go. I stay seated and wait, heavy and immobile.

I’m watching my thighs melt and me belly get round. I write about the bike while alternately flexing my legs under the table. I plan out routes in the desert; I read maps that show straight, arid lines stretching three-hundred kilometres between oases. I ask myself where on my handlebars I could attach compass and GPS.”

I can empathise with watching thighs melt and belly round – the real subject of Fournel’s Cairo essay – but of Cairo itself I can only say that in my experience, it’s an amazing city to cycle in. Seen from the pavement or the passenger seat of a taxi, Cairene traffic can seem like the dodgems, but once you get in between the cars its sense opens itself up and you quickly adjust to its rhythm and ways. Out of the traffic, riding along rutted Nileside tracks – or up the Sinai peninsula from Moses’s mountain to the Israeli border – were like slipping into another world, silent and beautiful. In later years I have gone back to Cairo, to explore the desert west and south of the city in a four-by-four, and each time have kicked myself for not having had the good sense to bring a bike with me.

You, obviously, won’t find the same thoughts creeping into your mind about Cairo. Maybe what Fournel writes of Paris or San Francisco will fire some mental fuses for you, make you agree with or question his experiences. Or maybe not. Not everything Fournel writes will send you off into a reverie. But you will find such launching pads in most of his essays.

The places that crop up the most in Vélo are French: the roads of the Haute-Loire where Fournel grew up, or roads defined by the Tour de France and other bike races. Martin Ryle is wrong to write Fournel off as a champion of turbo-culture but he is not entirely wrong when he says that Fournel writes of the pains and rewards of close-to-the-limit physical exertion and the heroes of bike races. Fournel himself says that “to get on a bike is to enter into a history and a legend that you’ll discover in thousands upon thousands of copies of L’Équipe.” He goes on:

The places that crop up the most in Vélo are French: the roads of the Haute-Loire where Fournel grew up, or roads defined by the Tour de France and other bike races. Martin Ryle is wrong to write Fournel off as a champion of turbo-culture but he is not entirely wrong when he says that Fournel writes of the pains and rewards of close-to-the-limit physical exertion and the heroes of bike races. Fournel himself says that “to get on a bike is to enter into a history and a legend that you’ll discover in thousands upon thousands of copies of L’Équipe.” He goes on:

It’s to forge your own fork in Saint Marie-de-Campan; it’s to jump into an air taxi after having won the Dauphiné to catch the nighttime start of Bordeaux-Paris; it’s to win the Tour de France five times; it’s to drop Merckx on the climb to Pra-Loup; it’s to keep Poulidor at bay on the Puy de Dôme; it’s to enter the vélodrome in Roubaix alone and for the second time; it’s to win the Giro d’Italia in the snowstorm of the Gavia; it’s, whether you like it or not, to fall into the chasm of the Perjuret and to die every time you climb the Ventoux on the Bedoin side … The divine solitude of the cyclist is peopled with shadows that the sun lengthens on the grain of roads.

Where Ryle is wrong in the way he writes off Fournel is to miss the soft edges of this ‘hard’ ethos Fournel – and many of us – subscribes to. Ryle is wrong to miss the conviviality of competition. All those memories Fournel recalls – of Eugène Christophe, of Jacques Anquetil, of Eddy Merckx, of Bernard Thévenet, of Marc Madiot, of Andy Hampsten, of Roger Rivière and Tom Simpson – what they’re really about is a sense of belonging, a shared heritage.

This shared heritage is one of the treats of Fournel’s essays. The real treat, though, is the effortless ease with which Fournel sucks you into his world: as I said at the start of this, Fournel is one of those rare cycling authors who you can take pure reading pleasure from, as everyone who has read Need for the Bike – which is often paired with Tim Krabbé’s The Rider when cyclists recommend books to one and another – will attest.

If you’ve already read Need for the Bike, should you want a copy a Vélo? The updating of cycling books is one of oddities of cycling publishing, how every few years an old book gets another couple of dozen pages stuck into it and you’re expected to buy it one more time. As an updated version of Need for the Bike, Vélo adds eleven new essays and some textual changes in the translation. But it also adds Jo Burt’s illustrations, the text and images combining to produce a book that is a pleasure simply to own. Of the new essays themselves, they are markedly different from the old, both in style and content and this – in a way – has the unfortunate result of upsetting the thematic unity of the original text (which tends to be the case with virtually every cycling book that gets the update treatment).

If you’ve already read Need for the Bike, should you want a copy a Vélo? The updating of cycling books is one of oddities of cycling publishing, how every few years an old book gets another couple of dozen pages stuck into it and you’re expected to buy it one more time. As an updated version of Need for the Bike, Vélo adds eleven new essays and some textual changes in the translation. But it also adds Jo Burt’s illustrations, the text and images combining to produce a book that is a pleasure simply to own. Of the new essays themselves, they are markedly different from the old, both in style and content and this – in a way – has the unfortunate result of upsetting the thematic unity of the original text (which tends to be the case with virtually every cycling book that gets the update treatment).

A few of those new essays do stand out, though. In one Fournel attempts to climb inside the mind of Jacques Anquetil. In another he offers a self-portrait of Abdel Kader Zaaf. The two that really stand out are further autobiographical sketches, Fournel once more revisiting his past. In one he revisits a incident that made up a brief paragraph in an earlier essay and this time spins it out to three pages. In the other Fournel writes of his father whose cycling life had come to a close while his other life carried on:

The bike left my father one Sunday morning ten years ago. It happened between Bas-en-Basset and Aurec in the Haute-Loire region of France, in solitude. He was climbing a small hill which I would not describe as laughable because cyclists – even those who are used to the Ventoux or Izoard – well know that you can explode in a two kilometres hill which doesn’t go up that much.

Let’s just say that this incline should not have been sufficient to end his riding.

‘Something’ tightened in his chest, imperiously letting him know that the bike was leaving him after seventy years of companionship.

He went home without saying anything, at the pace of his pain.

The rest of the essay picks up the story a decade on, Fournel’s father still able to recall the roads he once rode over. That, one day, the bike will leave all of us is not something we tend to give much thought to. But it will and all we will have are our memories. If nothing else, Fournel’s essays as a lock-pick for those memories, opening up for everyone who reads them memories parked from days gone by. If that’s not a good enough reason to read a good book then I don’t know what is.

Paul Fournel’s Vélo is published by Rouleur (2012, 159 pages)

No Comments