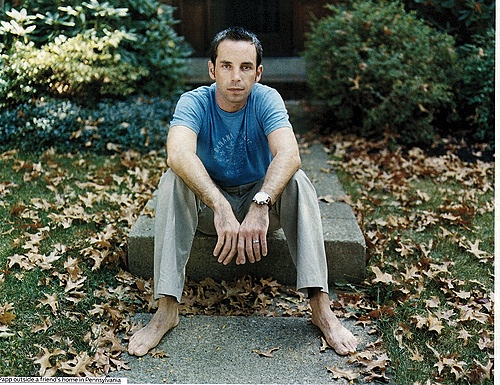

I am sitting in Joe Papp’s front room. It’s a nice room, pleasantly decorated and homey. I ask myself how pleasant and homey it will feel after several months of imposed house arrest, though. I decide against asking Joe this. No point spooking the poor bastard yet. Let him find out for himself that a bottle of Tequila is the best defense for when the demons start seeping out from the patterns in the wallpaper.

Chamfort’s dictum states that a person should swallow a toad every morning to be sure of not meeting with anything more revolting in the day ahead. It’s good advice, which I recall having given to Joe when I bumped into him a couple of years ago (Don’t ask. It involved Herman Cain, a high-class call girl and a prominent member of the IOC, but I don’t want Papp getting into any more trouble). Joe replied that his batrachian breakfast was simply looking in the mirror each morning. Christ, and I thought I was dark.

I skirt the issue and ask him how he’s doing? “I’m fine, Winston,” he replies. “Sure, being under house arrest is no fun. Did you know that the last tin of beans I opened had 452 beans in it?”

Jesus H. Merckx, I think. This kid’s gone ga-ga already! I think about asking him if he has any brandy and wonder if I have any Ketamine in my bag. Best no, I conclude. Last time I did Ketamine and brandy was with Pantani. And we don’t want any repeats of that shit.

I ask him about his future and where he sees himself going from here. Papp tells me that he wants to help and that he has been helping the authorities over the past few years to use what he knows in order to catch other cheats in the sport.

“How many?” I inquire. He says he believes it’s somewhere in the region of about 20. I laugh and when Joe asks me what’s so funny, I point out to him that this is probably more than Pat McQuaid has achieved in a similar period. His face cracks a smile at that, but he positively bellows when I suggest that he should run for UCI President. “I don’t think the world would ever want to see that – once a cheat, always a cheat, right?”

I suggest to Joe that I tell him a story and he eases back in his armchair a little, accepting my request. “In 1975,” I begin,

I was working as a sports reporter for some shitty London rag thast, frankly, didn’t deserve my services (nothing new in that, though). Since no one else could be bothered sitting on a plane for upwards of 12 hours, yours truly was dispatched to South Africa to cover the contentious Rapport Toer. This race had been set up a couple of years earlier and was sponsored by the country’s Department of Sport and a national Sunday newspaper. It ran from Cape Town to Johannesburg, covering about sixteen-hundred kilometres over three weeks of racing. Teams from Europe came and raced in unofficial national teams and raced against local squads. The reason they were unofficial was, of course, that racing in South Africa had been banned by the IOC because of the apartheid regime.”

Everyone knew that the European riders in the race were prominent racers. These guys were looking to keep their race fitness up to par ahead of the Olympic Games in Montreal the next year. But as long as no one rocked the boat, everything would be OK.”

“Doesn’t that sound familiar?” I ask Joe. He smiles again, before asking me to go on.

I recognised Sean Kelly immediately when I saw him on the start line of the opening stage. Sean is a likable guy and I was impressed by him even as a 19 year old – like a drink too, of course. I also recognised Keiron and Pat McQuaid. All the McQuaids were self-important, jumped-up little shits. Their father, Joe, had seen fit to instill a troubling sense of entitlement in his boys and Patrick, especially, wandered about the départ trying to make himself look like Merckx himself to all the local South African riders. I could tell you some stories about Joe, too, but we’ll save them for another time.”

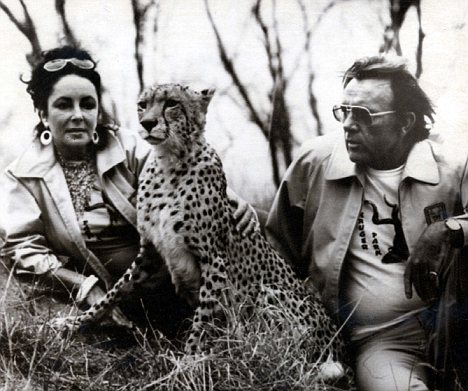

A reporter from the Daily Mail was also in South Africa at the time. His name was John Hartdegen but he wasn’t there to cover some poxy bike race. John was there to follow Liz Taylor and Richard Burton who just so happened to be on honeymoon. John and I had known each other for a while – nice guy, calls a spade a fucking shovel and can handle both drink and women with ease and grace. Sorry, I digress.”

John asked who he should speak to about getting some photos of some of the British riders with Liz Taylor, as he thought this might make a good story. Knowing full well that this would be the last thing they would want, I suggested that Hartdegen talk to British team’s manager, Tommy Shardelow. I did find it funny when John came back saying, “There’s something weird about this British cycling team. First of all their team manager didn’t want them to be photographed with Liz Taylor, and then when I did finally manage to get them to appear a few of them spoke with South African accents!”

Johannesburg 1975: Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton made a friend in the African bush during a visit to South Africa's Kruger Game Park

That stupid bastard Shardelow had tried to fob a reporter off by sending members of other teams to the photoshoot. In fact, far all I know they may just have been some South African blokes plucked off the streets and shoved hastily into tracksuits. I told John, rather mischeviously, that he should go and have it out with Shardelow as his journalistic integrity was on the line here.”

As soon as this happened, Shardelow caved and admitted that these weren’t the real British riders and that he couldn’t risk the real riders being photographed as they were riding in the country illegally. Besides, three of them weren’t even British. The McQuaids and Kelly were Irish and the other two, Henry Wilbraham and John Curran, were Scottish.”

John showed me the photograph that had been taken and the list of names he had been given. After I stopped laughing I told him who they really were but he should send this to London to get it confirmed.”

The result of all this was that the Daily Mail ran a full-page story on the riders’ little escapade, the McQuaids and Kelly were handed a seven-month ban (commuted to 6 months on appeal) by the Irish Cycling Federation. They felt that they had gotten off lightly and that the dreams of competing at the Olympics were still intact. As Pat McQuaid said to Paul Kimmage later, “Going to South Africa was even then considered a major crime in cycling. But, deep down, I thought we were too good for them to fuck us out.”

The UCI had other ideas and through its amateur arm, the FIAC, it compiled a list of the real identities of as many of the Rapport Toer riders as it could identify. That file was passed to the IOC, who decided on May 29th, 1976 that sixteen riders from seven countries who had been identified should be given lifetime bans from Olympic competition. Kelly and McQuaid were among them.”

I conclude my yarn by telling Papp that Pat McQuaid continued as an amateur cyclist but eventually turned his hand to the organising the sport instead. Family connections and the aforementioned air of entitlement helped Pat become a board member of the Irish Cycling Federation in 1985 and then its president in 1994. “No, I’m not sure how many bottles of fine Irish Malt were involved in that one,” I tell Papp. In 1998, the conniving little bastard moved on to the UCI, where, as we all know, he became president in 2005.

I lean over to Joe and ask if he wants to know the supreme irony in all this. There’s a glint in Joe’s eye now. One I haven’t seen in a long time. “Sure,” he says. Well, in 2010, despite never again being allowed to throw his leg over a top tube within a 50-mile radius of the Olympic flame, old Patrick became a member of the International Olympic Committee.

“It’s a funny old world,” I tell Joe as I get up to leave his house. You never, never know. We might yet be asking a sign-writer to the paint the name Joe Papp on the President’s door in Aigle. Stranger things have happened.

1 Comment

[…] more on this story over at the Cyclismas blog. Thanks to Cillian for flagging it […]