With introductions out of the way, we now turn to one of the key issues affecting cycling in the 1924 season: the demand by Italian teams that the Giro d’Italia organisers pay appearance fees.

* * * * *

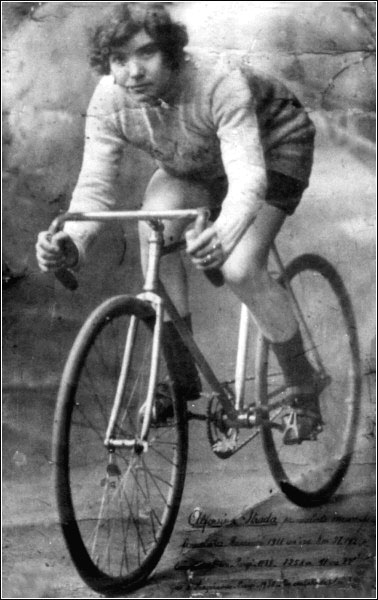

The reason Emilio Colombo and Armando Cougnet invited Alfonsina Strada to ride the 1924 Giro d’Italia was simple: the big teams were pressing the Giro organisers to pay appearance fees simply for starting the race. The Giro was refusing their request. So the big teams were threatening to boycott the Giro.

Appearance fees were – still are – a part of cycling. If you can’t count on the stars to willingly ride your race, sometimes you just have to cross their palms with silver in order to ensure their presence. When Lance Armstrong returned to the peloton in 2009, his palm was greased generously by the organisers of many races, including the Giro d’Italia. But there’s a world of difference between paying off a star or two to grace your race with their presence and having to pay off whole teams who should be entering your race as a matter of course. There is also a world of difference between buying in a star now and then and having to fork out for both stars and bit-part actors every single year.

One can presume that, once the teams had won their battle with the Giro d’Italia, they would soon turn their attention to La Gazzetta‘s other races, particularly Milan-Sanremo and the Giro di Lombardia. Colombo and Cougnet were in no mood to meet these early revenue-sharing demands. The Giro was already paying generous prize money. When it was launched, the race was trumpeted (hyperbolically) as the richest in the world, with a prize fund of 25,000 lire. By the mid-twenties, that was up around 100,000 lire annually between 1923 and 1926. In the same period, the Tour’s prize fund had grown from 25,000 French francs in 1909 to 100,000 in 1924. (Exchange rates in 1924: approx 87 French francs to the pound, 19 to the dollar; 102 lire to the pound, 23 to the dollar.) As far as Colombo and Cougnet were concerned, they were already being more than generous when it came to paying people to ride the Giro. In the pages on La Gazzetta dello Sport, race director Cougnet accused the teams of “behaving like spoilt theatre actors.”

This, of course, wasn’t the first time the teams at the Giro could be accused of behaving like spoilt theatre actors, and it certainly wouldn’t be the last. Bianchi, in particular, had a reputation for throwing strops at the Giro. In the second race, 1910, the whole Bianchi squad had withdrawn on the second stage, for reasons unknown. And 1922 saw one of the best strops in Giro history.

It’s a long and somewhat convoluted story, but at its heart is the simple rule that technical assistance was, back then, outside the rules. So Legnano’s Giovanni Brunero was clearly breaking the rules when, having flatted, he took a wheel change from teammate Alfredo Sivocci (who then took a wheel change from teammate Pietro Linari, who took a wheel from the next Legnano rider to turn up, Franco Giorgetti, who had to wait for Ruggero Ferraro in order to get a crossbar to the next control station).

Maino, who were expecting Costante Giraradengo to do the business for them, and Bianchi, who were resting their hopes on Gaetano Belloni, both leaped at the chance to get a serious threat like Brunero turfed off the race. They both complained about his illegal wheel change. The commissaires listened to them. Brunero was out. Legnano appealed. Not for nothing was their DS, Eberardo Pavesi, known as l’avvocat. Pending his appeal, Brunero was back in the race. It was like an Italian hokey-kokey.

It took the Italian cycling fed another two stages to decide Brunero’s fate: a 25-minute time penalty. With the hills still looming and Brunero a scalatore of some skill, that time penalty was little more than a slap on the wrist. Realising they were about to get their arses kicked again – Brunero had won the previous year – both Maino and Bianchi used the affair as an excuse to pull out of the race, muttering loudly about the unfairness of it all as they left.

With the teams having incidents such as these in their past, and now threatening to not even take the start unless they got what they wanted, you can see why Cougnet was minded to call them spoilt theatre actors.

The teams, of course, couldn’t imagine Colombo and Cougnet not bending to their will. They themselves had been there at the birth of the Giro: Atala got word that Bianchi, along with the Corriere della Sera, intended to launch a Tour of Italy, and took the news to La Gazzetta dello Sport, who then gazumped their rivals by pre-emptively announcing the birth of the Giro d’Italia.

From the outset the Giro had declared itself a race for teams, unlike the Tour de France, where Henri Desgrange was fighting a long and losing battle with the mighty marques. The Giro had even once been run purely for teams, in 1912, when (technically) there was no individual winner. But while that race was won by Atala, it was Carlo Galetti who was the real star and still gets the credit for the victory. La Gazzetta quickly realised that the tifosi cheered for riders, not teams and reverted to individual winners thereafter. Even so, the teams, figured they had the weight of history on their side and stuck to their guns: appearance fees, or else.

Colombo and Cougnet were having none of this and dug their heels in: no appearance fees, no matter how big the stars. The race made the stars, not the other way round, a point many race organisers had proved down through the years, especially Pierre Giffard (at the 1891 Paris-Brest-Paris) and Henri Desgrange and Géo Lefèvre (at the Tour). If the stars of the day didn’t want to ride their race, then Colombo and Cougnet would just have to create new stars to replace them.

The teams continued to withhold their stars, figuring Colombo and Cougnet would cave, that they simply had to be faking their moral indignation. They weren’t. Thumbing their noses at the teams, Colombo and Cougnet called on Strada. The Queen of the Cranks was in and the stars were out.

That the teams were willing to pass up the biggest publicity opportunity of the season demonstrates that they did at least believe in what they were arguing for, that this wasn’t just about petty posturing and silly name-calling. The fact is, cycling was turning into a very expensive sport, and the people who funded it were being bled dry by the demands it was putting on them.

Back at that first Giro in 1909, Atala hadn’t just spiked the guns of Bianchi in the birth of the race by taking the news to La Gazzetta. They had also snatched Luigi Ganna from under Bianchi’s nose, topping the 200 lire a month Bianchi were paying him with an offer of 250 lire. Ganna signed on the dotted line and then went on to win the inaugural Giro for Atala. (Ganna actually finished the race 37 minutes behind Bianchi’s Giovanni Rossignoli – who was still racing in 1924 – but the early Giri were based on points, not time, and the Bianchi rider placed fourth on GC.) The next year it was an Atala lock-out on the Podium (Bianchi had thrown a hissy-ft and left the race), with Ganna finishing third, behind Eberardo Pavesi and Carlo Galetti. Bianchi had to wait until 1911 before they got their first Grand Tour victory, they having lured Galetti away from Legnano (who had lured him away from Atala) by offering him yet more money. A year later Atala upped the ante and had Galetti back on board. In Italy in those days, the best riders were very mobile and regularly changed teams.

Throughout the sport, salaries had spiralled before the war as teams, awash with cash from a booming bicycle trade, outbid one and other for the stars of the moment. The world was rich and the riders reaped the reward. The war brought all that crashing down. Coming out of the war, the main French marques – Alcyon, Automoto, La Française, Labor and Peugeot – banded together under the title La Sportive, which was ruled over by the man they called the Marshal, Aphonse Baugé. No longer capable individually of financing strong teams, collectively they were able to exert a stranglehold on French cycling and keep the lesser lights of the French bicycle industry in their proper place. Most riders signed to La Sportive rode for expenses, only a select few receiving a salary. Even for those who were paid monthly, what they received was tiny compared with what was being paid before the war. Henri Pélissier, for instance, was earning 3,000 francs a month before the war at Peugeot. After the war La Sportive were paying him just 300 francs a month.

La Sportive lasted for three years, before being broken up in 1922. Or partly broken up: the member marques created a cartel, setting salary and budget caps. For a cartel to work, though, two things need to happen: the members need to abide by the rules; and the cartel has to be strong enough to strangle non-members before they can become a threat. In France, La Sportive’s members failed first at the latter, the Pélissiers helping JB Louvet rise to power, and then at the former, when Automoto broke ranks – and the salary cap – and outbid Louvet for the services of the Pélissiers. By 1924, the French cartel had more or less crumbled.

In Italy at this time Bianchi and Atala were relatively weak on the road, their best riders having been lured away from them. But they still carried political clout. The real teams of the moment were Maino and Legnano. The argument with the Giro organisers over appearance fees was being led by Bianchi and Atala and was supported by Maino. Legnano … well Legnano managed to hedge their bets by both supporting and not supporting the boycott.

The man behind the Legnano marque was Emilio Bozzi. He had bought the Legnano marque from Vittorio Rossi shortly after the end of the war. In 1924 he was one of the rising men of Italian cycling. And with Pavesi as his DS he was writing the name of Legnano into Italian cycling’s history books. In 1924, Bozzi and Pavesi were fielding a team of champions: in their pay at this time were the winners of the 1920-22 Giri – Gaetano Belloni (1920) and Giovanni Brunero (1921 and 1922) – as well as Pietro Linari, who was Italy’s sprinter par excellence. They also had Giuseppe Enrici, an American-born Italian who, in his first season just two years earlier, had finished on the bottom step of the Giro’s podium.

Bozzi and Pavesi withheld Brunero, a two-time winner, from the Giro. Were they supporting the boycott? Obviously that position could be argued. But the reality is that Brunero was being saved for a serious tilt at the Tour de France, which so far no Italian rider had been able to win (the best Italian riders typically having ridden the Giro before the Tour). A large number of Bozzi’s riders did turn up for the Corsa Rosa, including Belloni, Enrici, Bartolomeo Aymo, Arturo Ferrario, Alfredo Sivocci, Ermano Vallazza, and Adriano Zanaga. Belloni wouldn’t figure in the race after the opening stage but Aymo, Enrici, Ferrario, Sivocci, and Zanaga would all feature prominently.

Also absent was one of the stars of the 1923 Giro, Ottavio Bottecchia, who was riding for the French Automoto squad. Automoto had signed the Italian the previous year partly because they were making a move on the Italian market, and having a native rider in their ranks would help them get column inches in the Italian press. But they were still a French team at heart: the Tour was their race, not the Giro.

In the absence of the major stars – Girardengo, Brunero, Bottecchia – La Gazzetta sought to encourage individuals to enter the race. Technically, all the riders in the 1924 Giro were isolati, riding without the support of a team network, but many riders – including the lads from Legnano – were still sponsored and the sponsor would still get a boost from whatever success they could achieve in the race. But, without the major riders from the mighty marques, the Giro organisers still needed to find a way to entice the lesser lights of the sport to enter their race. Other race organisers before them had already faced similar problems in cycling’s short history.

Back in the nineteenth century, Véloce Sport organised the first Bordeaux-Paris race, a 575 kilometre jaunt for the two-wheeled stars of the day. The real stars of the day happened to be British, and they managed to knobble the opposition early by insisting they wouldn’t race against professionals. The British sense of fair play, the fabled Corinthian Spirit and all that what, what, what? Hardly. The British just knew the power they held over Véloce Sport: if they demanded that the race exclude pros, Véloce Sport would bow to their will. They also knew that their real opposition – the French riders – all rode as pros. Defeating them before the race even got underway was far, far easier than defeating them on the road. And once the French riders were barred from riding their own race, the British were able to sign them up and set them to work on pacing duty (most early races featured some form of pacing: Paris-Roubaix was still being paced as late as 1909, and – of course – pacing was a feature of Bordeaux-Paris right through to its demise in the 1980s).

When Pierre Giffard at Le Petit Journal saw the success of Bordeaux-Paris, he decided to launch his own race: Paris-Brest-Paris, a mere 1,200 kilometres of pedalling. But Giffard had seen the way the British riders had bent Véloce Sport to their will and he decided he wasn’t going to let the teams and the riders hold him over a barrel. Giffard figured he actually held the upper hand: he was a media man who didn’t just believe in the power of the pen, he knew full well the power of the printing press. He appealed to one of his readers’ most base instincts: patriotism. Paris-Brest-Paris would be a French race for French riders. Giffard then proceeded to talk up the fact that rank amateurs would probably outride the stars of the day. Not only did this ensure that the stars of the day would have a point to prove, but it also encouraged a lot of amateurs to suffer delusions of grandeur. Paris-Brest-Paris’ entrants topped 600, with 200 of them actually turning up for the start. And at the end of it Charles Terront – one of the French pros the Brits had sought to knobble in Bordeaux-Paris – won the race. As he steamed over the Porte Maillot, 10,000 people cheered his progress. Giffard had played a blinder: the public loved his race and a real star had won it.

Skip the story forward a couple of decades. When Géo Lefèvre hit upon the bright idea of the Tour de France, L’Auto Vélo had to face up to the fact that their race might be too tough for the stars of the day, most of whom rode short distances on the track. Not a problem, they decided, they would make the men who did ride it into stars. But they still had to entice enough men to get on their bikes for such a crazy endeavour as a race around France. In the end, the only way they could do this was by lowering the entrance fee, shortening the race, and raising the per diem that was being paid to all participants.

History, then, was affording Colombo and Cougnet at least two examples for dealing with their problem: patriotism and filthy lucre. Neither was really a runner in 1920s Italy, so they found a third way: they figured that the quickest way to a man’s heart was through his stomach. As part of their lure they published details of how much food they were providing for participants: chickens (600), other meat (750 kilograms), eggs (7,200), bananas (4,800), bottles of mineral water (2,000), and butter (50 kilograms) along with assorted bread, jams, biscuits, chocolate, apples, and oranges.

On a daily basis, each rider was getting 250 grams of meat, a quarter of a roasted chicken, two sandwiches of prosciutto and butter, two jam sandwiches, a hundred grams of biscuits, 50 grams of chocolate, three eggs, two bananas, and a litre of mineral water. Today, you might question whether you’d be willing to ride to the shops for such fare, but in 1924 Italy, that was a veritable feast for the cycling classes. The Giro got its desired number of entrants. Ninety riders, all officially riding as isolati, would leave Milan on May 10th, with Alfonsina Strada among them.

Next: The 1924 Giro gets underway.

* * * * *

Sources: If your Italian is up to snuff and you’d like to learn more about Strada, seek out Paolo Facchinetti’s Gli Anni Ruggenti di Alfonsina Strada (The Roaring Years of Alfonsina Strada). , which has also been translated in the Netherlands as Het Roerige Leven van Alfonsina Strada.

Strada’s story is also touched upon in the three Giro-related books to land last year: Bill and Carol McGann’s The Story of the Giro d’Italia – A Year by Year History of the Tour of Italy, Volume I, 1909-1970 (McGann Publishing), which is a valuable source of year-by-year race data; John Foot’s Pedalare! Pedalare! – A History of Italian Cycling, which succeeds in its attempt to try and see Italian cycling of the campionissimi era in a wider cultural context; and Herbie Sykes’ Maglia Rosa – Triumph and Tragedy at the Giro d’Italia, which is filled with wonderfully told stories of the men whose legends were made by the Giro and who have in turn forged the legend of a race that is often far more fascinating than its over-exposed French cousin.

Those three books, along with Benjo Maso’s Sweat of the Gods: Myths and Legends of Bicycle Racing (Mousehold Press), are the main sources for the above.

3 Comments

[…] cycling season, the first Grand Tour of the year, the Giro d’Italia, finally gets underway, without most of its major stars and with Alfonsina Strada among the ninety starters. The Giro d'Italia, circa […]

[…] cycling season, the first Grand Tour of the year, the Giro d’Italia, finally gets underway, without most of its major stars and with Alfonsina Strada among the ninety starters. The Giro d'Italia, circa […]

[…] parts we’ve looked at the the 1924 peloton in general (part 1), the 1924 Giro d’Italia (part 2 + part 3), what happened to Alfonsina Strada (part 4) and the role played by the Giro in the […]