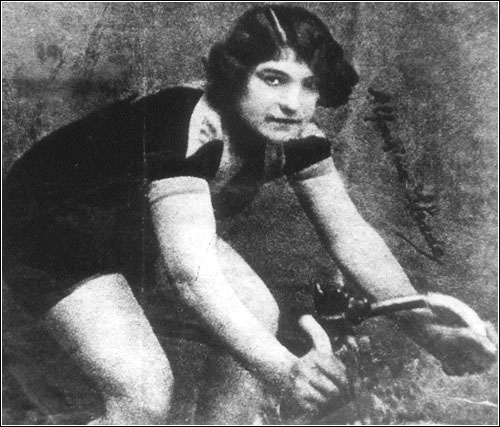

Before moving on to the other Grand Tour, we pause the story of the 1924 cycling season to consider what happened to Alfonsina Strada next.

Alfonsina Strada, the woman who had helped save the 1924 Giro d’Italia, was buried in 1959. Ottavia Bottecchia, Henri Pélissier and Albert Londres – the other three names most remembered from the 1924 cycling season – were already in their graves. There are some races you’re happy to finish behind others in. Strada was sixty-eight when she died. Not a bad innings for someone born in the last decade of the nineteenth century.

Cycling was Strada’s escape from a peasant’s existence. While many of her male contemporaries appreciated and applauded her, cycling was then very much a male-dominated sport. It still is, I suppose, but more and more people are beginning to wake up to the existence of the distaff peloton and who knows, maybe within our own lifetime the publicity scales may even balance out and it will receive the media attention it deserves. But the way it is today is far, far better than it was in Strada’s time. The women who rode bikes in those days were too often seen as little more than vaudeville acts, not treated as athletes. Cycling itself, though, was – to some extent – itself a vaudeville act. Men like Henri Pélissier wanted to turn it into a sport about athleticism, men like Henri Desgrange wanted it to be about who could endure the most suffering and still ride into his vélodrome.

From the age of ten, when she first rode her father’s newly-acquired bike, to her dying day, Strada was a cyclist. The fame her cycling exploits earned her enabled Strada to travel, to Russia, to Spain, to France, to Luxembourg, and earned her a better income than her parents had known, and more too than she would have earned had she followed their advice and become a seamstress. As late as 1937 and 1938 Strada was still racing, and still winning.

Cycling may have enabled her to escape poverty, but nothing could save her from a hard life. Her husband, Luigi Strada, the man who gave her a racing bicycle as a wedding present, suffered a mental collapse and was institutionalised. The 50,000 lire Strada won at the 1924 Giro went to the Milanese mental institution to which he had been confined. He died in 1946.

Four years later Strada remarried. Her second husband was Carlo Messori, the cyclist from her native Emilia who had encouraged a teenaged Strada – then still Alfonsina Molini – to continue with this cycling lark. He himself had by then retired from cycling and was running a bike shop in Milan. During their marriage Messori tried to put together a biography of his wife’s life and cycling career, but no publishers showed an interest in her story.

Messori died in 1957 and Strada was widowed for a second time. She continued to run the bike shop herself and continued to support the sport she loved, even though she herself was increasingly being forgotten by a sport which each year churns out new heroes for us to get excited about. In September 1959 Strada returned from a day at the bike races, the Tre Valli Varesine, where Dino Bruni had won. She told the porter at her apartment house that she’d had a wonderful day. She then suffered a fatal heart-attack. Another page of cycling history had been turned.

Strada’s story though was too good to be forgotten for long. In 2004 Paolo Facchinetti was able to publish his Gli Anni Ruggenti di Alfonsina Strada (The Roaring Years of Alfonsina Strada) and when the Giro started from Amsterdam in 2010, a publisher in the Netherlands published a Dutch version of it, Het Roerige Leven van Alfonsina Strada. An English-language publisher has yet to show an interest in the book. Strada’s story has been put on the stage, in Italy – a version of which is playing in London this year – and featured in an album of cycling tracks by the band Tete de Bois. And, if you visit the chapel of the Madonna on the Ghisallo, you can see one of Strada’s bikes among the other relics of cycling’s glorious past.

But does Strada’s story matter today? I think it does. First, and foremost, it’s a good story, a story that deserves to be told and retold. But cycling is full of good stories that deserve to be told and retold. And Strada’s is, at least, told: there are many names in the forgotten history of our sport who have yet to have their stories told.

And of course, yes, the cycling of those days is now anachronistic; we can’t even imagine bikes that weighed twenty kilograms and didn’t have gears, let alone get our heads around the condition of the roads over which the riders of the day raced. But that’s just detail: look at the big picture and see that what was happening in 1924 is still happening in 2012. The big teams are still pleading with the Giro and other race organisers for a bigger slice of the pie.

And why should we bother with the retelling of a story from the past when – for female cyclists especially – the story of the present is only barely being told in the mainstream media and even in the main cycling journals? Would we not be better just forgetting all about Alfonsina Strada and telling the stories of the women racing today? If it was simply a choice between one and the other, than yes, forget the past, talk only about the present.

But can’t we do both at the same time? Cycling’s past is, after all, what makes its present seem so alive. The riders of today are not just racing against one and other, they are racing against the legends of the past. This is one of the areas where women’s cycling still needs help: its past is being forgotten and, without its past, its present doesn’t shine as brightly as it should. Connect the stars of today with the stars of yesterday and both will shine brighter. Maria Canins, Beryl Burton, Connie Carpenter, Keetie van Oosten-Hage, Yvonne Reynders, Petra de Bruin, Ingrid Haringa, Elsy Jacobs, Hélène Dutrieux, Oenone Wood, Louise Armaindo, Anna Millward, Leontien van Moorsel, Yvonne McGregor, Jeannie Longo – all of those names should be as recognisable as any of the giants of the road from Coppi to Anquetil, Merckx to Hinault, Kelly to Cavendish. How many of them are?

Help people undertand who they are, what they did, and you do actually help the current peloton, by providing a yardstick against which it can be measured. And that’s why Alfonsina Strada’s story still matters. It’s not just about the past. It’s also about today.

* * * * *

Sources: If your Italian is up to snuff and you’d like to learn more about Strada, seek out Paolo Facchinetti’s Gli Anni Ruggenti di Alfonsina Strada (The Roaring Years of Alfonsina Strada), which has also been translated in the Netherlands as Het Roerige Leven van Alfonsina Strada.

Strada’s story is also touched upon in the three Giro-related books to land last year: Bill and Carol McGann&’s The Story of the Giro d’Italia – A Year by Year History of the Tour of Italy, Volume I, 1909-1970 (McGann Publishing), which is a valuable source of year-by-year race data; John Foot’s Pedalare! Pedalare! – A History of Italian Cycling, which succeeds in its attempt to try and see Italian cycling of the campionissimi era in a wider cultural context; and Herbie Sykes’ Maglia Rosa – Triumph and Tragedy at the Giro d’Italia, which is filled with wonderfully told stories of the men whose legends were made by the Giro and who have in turn forged the legend of a race that is often far more fascinating than its over-exposed French cousin.

Those three books are the main sources for the above, with additional information on Strada drawn from the Italian Cycling Journal and Radio Marconi blogs.

3 Comments

[…] that sparked the teams’ boycott of the 1924 Giro d’Italia and opened the door for Alfonsina Strada to become the only woman to ride a Grand […]

And differing judgments serve but to declare That truth lies somewhere, if we knew but where….

Toll for the brave, The brave! that are no more: All sunk beneath the wave, Fast by their native shore….

[…] (part 1), the 1924 Giro d’Italia (part 2 + part 3), what happened to Alfonsina Strada (part 4) and the role played by the Giro in the revenue-sharing debate (part 5). We now turn to the other […]