“As a human being … Merckx is a human being. He is not a saint. He was treated like one from the age of twenty-one – and after that you have to be superhuman to be human, extraordinary to be ordinary. You have to be bigger than bigger than big to be beyond that kind of adulation.”

~ Walter Pauli

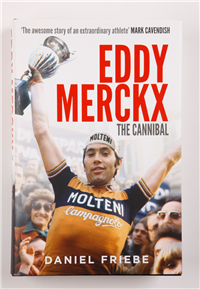

Within the first 300 words of Daniel Friebe’s biography of Eddy Merckx the words ‘different’ or ‘difference’ appear four times. Over the next few pages one or other word keeps reappearing. Is it that Friebe simply has a limited vocabulary and no thesaurus? No. The choice of words is quite deliberate:

Higher, faster, stronger, said the Olympic ideal, its three pillars the very synthesis of sporting advancement – but nowhere did it mention difference. For when as early as 1968, newspapers started saying that Merckx was ‘in another league’ and ‘racing against himself,’ they weren’t only saying that he was much better than the rest. ‘No, at times it was actually like a different sport,’ observes former opponent Johnny Schleck. Different from the past, from the sport Anquetil had dominated before Merckx, and the Italian Fausto Coppi before him. Different from the one now practiced by his contemporaries.”

That word then can be taken as one of the key themes of Friebe’s Eddy Merckx – The Cannibal. Friebe isn’t just offering a portrait of Merckx himself, he offers portraits of some of the men Merckx raced with and against, the men to whom Merckx was different. Understand them – understand the era they raced in – and maybe you can begin to understand Merckx himself. (And, by the by, maybe you can also better understand the sport we know today.)

Merckx himself declined a request to be interviewed by Friebe; he’s contractually tied to his own, official project and thus not offering assistance to anyone else. But, as Friebe correctly notes, Merckx is probably the last person you should speak to in trying to understand the enigma that he has become. After all, Merckx himself only knows Eddy Merckx, and thus “can’t quite understand the fuss because his life is the only one he has ever known.”

Merckx’s palmarès, as noted elsewhere, are impressive, touching just about every race of note in our sport. Almost wherever you turn in cycling, you run into Eddy Merckx. It’s funny, then, that having declined to participate in Friebe’s attempt to tell his story, the two – Friebe and Merckx – can’t seem to avoid one and other. Like Alfred Hitchcock – or the ghost of Banquo – Merckx just has to make an appearance.

In one cameo Friebe is talking to Felice Gimondi during the 2011 Giro d’Italia, in a VIP enclosure overlooking the finish line in Macugnaga. Paolo Tiralongo is about to pip Alberto Contador to the stage win, but Friebe and Gimondi are a world away, discussing the 1968 Volta a Catalunya. In walks Merckx himself, over to the table being shared by interviewer and interviewee, and takes a seat next to Gimondi, who immediately incorporates Merckx into the story being told:

Gimondi: Eddy, when was it that we first met? Bruxelles-Anselberg in 1963, when we were still amateurs?

Merckx: You beat me. You made me suffer like a beast. [Laughter.]

Gimondi: It was the only race he let me win! All the others you won after that […] That time trial in the Volta a Catalunya still burns. I still think about it now. At midnight, I was still down on the beach, the Playa de Rosas – walking up and down, up and down – trying to figure out how you’d beaten me in a time trial…

Merckx: I’d broken my wheel. I broke two spokes. I had to change a wheel.

Gimondi: You? In that one, too? I didn’t know that … Anyway, it took me two years to swallow what happened that day and finally understand why he’d beaten me. He was just stronger. But do you remember that Volta a Catalunya? This huge battle, knives out in every stage. One day, I had a problem after five or six kilometres, and on they all went, into battle. The next day, you had a problem, and off we all went. The jersey went back and forth two or three times that week. And then, in the end, as always, you won.

At which point in the conversation Merckx gets up and walks away, as silently as he’d arrived.

Ok, I know, that story should come with a spoiler alert, bite me. But, for me, it helps highlight one of the strengths of the story Friebe is telling. It’s not so much what Gimondi says that matters – ‘Merckx whipped my arse, it hurt at the time but I can laugh now’– but the scene itself and the way he tells his story. What the telling of that tale says about Gimondi. And what that scene says about Merckx.

* * * * *

Because Merckx touches so much in cycling, the basics of his story are familiar to almost anyone who has read a couple or three of the better-selling cycling books, or read a couple of cycling magazines for a year or two. Because Merckx is the rider against whom just about everyone else is now measured, elements of his story are constantly being told and retold. One of the curiosities of this is that Merckx’s story still feels like it happened in the recent past, isn’t yet a tale being excavated from history. But, as Friebe notes early in The Cannibal, the past is catching up with Merckx’s era:

I never saw Merckx race, and neither, in too long, will anyone have witnessed him in action. Merckx’s generation is getting older, dare we even say, old. […] The truths they never told, the memories they never shared, are nearing expiry. As this happens, a new and less gilded recollection of their era begins to take hold.”

It’s now forty-six years since Merckx took the first major victory of his professional career, the 1966 Milan-Sanremo, and thirty-six years since the last (poetically, also Milan-Sanremo). In three years’ time Merckx will have got to the end of his allotted three score years and ten, and who knows how many bonus laps he’ll have in store after that (if it’s true that a good Tour takes one year off your life and a bad one three, then Merckx – who started seven Tours – is already past his sell-by date in cycling years). It’s worth spelling out here just how much the past has already caught up with Merckx’s generation: men like Tom Simpson (his team-mate at Peugeot), Vincenzo Giacotto (his directeur sportif at Faema and Faemino), Jean van Buggenhout (his agent and manager), Jacques Anquetil (whose decline coincided with Merckx’s rise), Louis Ocaña (one of Merckx’s few true rivals in the Tour), Enrico Peracino (the Faema team doctor), Maurice de Muer (directeur sportif to Ocaña and later to Bernard Thévenet, the man who ended Merckx’s reign of terror in the Tour), and a host of others have all already passed away. If that seems rather morbid, so be it. But it’s still the truth. Whatever those men had to say about Merckx has already been said, their contributions to the Merckx story are fixed in the books they wrote and the interviews they gave. But there’s still time to hear from the men who survive. Time to see if, as Friebe suggests, the march of time has loosened their tongues, to see if distance has added clarity to their view of that era.

So what do those who knew Merckx from within the peloton have to say of him today? Consider these recollections of Merckx’s arrival on the cycling scene and his early run of victories:

Felice Gimondi:

I mean, how were we supposed to know? I had won the Tour de France in my first year as a pro [1965], I was about to win another Giro [1968]. Everything was going well … Who knows how many more Giri d’Italia I’d have won if he hadn’t come along. But he did come along. And we didn’t realise for months, years.”

Dino Zandegù:

We were all intimidated. We were. This kid just arrived, this big, handsome Belgian kid with high cheekbones – the face of an immense athlete – and pretty quickly we all realised that on the bike he was a brute. I say quickly but it wasn’t straight away. It took a while, a couple of years. We, we didn’t know, we didn’t …”

Italo Zilioli:

No wonder I looked miserable as sin when a photographer asked me to pose with Eddy just after I’d seen that [Merckx’s stage win at Blockhaus in the 1967 Giro]. Of course Eddy won again two days later. With hindsight, that should have been the penny dropping …”

Walter Godefroot:

We were too immersed in our own careers to see what was going on. To an extent, we only realised what had happened when it was too late …”

We didn’t realise… We didn’t know… That should have been the penny dropping… We only realised when it was too late … All comments that bear repeating, because they help paint a picture of the cycling scene as it existed back then, as it was seen back then, not how it has come to be seen with hindsight. Yes, Merckx blasted onto the scene, but it took a while for people to realise it. And, as Merckx’s decline set in, it took them longer, still, to notice that too.

You can count Merckx’s period of domination as either being between 1966 and 1976, his first and last major wins as a pro, or between 1968 and 1974, his first and last Grand Tour victories. In the latter instance Merckx left others to fight it out for just two Tours de France, two Giri d’Italia and all bar the one edition of the Vuelta a España he took part in: that’s nine Grand Tours in all for the others, compared to the eleven that went to Merckx. The picture is slightly different when you look at his reign of terror in the Monuments: nineteen to Merckx, thirty two to be shared out among his rivals. Yes, Merckx put his fellow professionals in the shade, but they had their days in the sun too. But – in the longer term – it’s racing against Merckx, being defeated by Merckx, that has added the most to their stories. Look, for instance, at Louis Ocaña. More is written about the Tour de France he lost (1971) than the one he won (1973). Or consider this comment from Felice Gimondi, the man who twice benefited from Merckx’s doping busts (the ’69 Giro and the ’73 Lombardia) and who described his time in the peloton alongside Merckx as being both friendly and beastly:

Today, I look back and I’m glad that my generation and I had Merckx. I’d have won more without him there, earned more, but life isn’t just about money. The respect, the rivalry, the memories … they’re all more valuable. Even three million euros more doesn’t have the same impact on your life as that stuff, some of the battles I had with Eddy.”

Friebe suggests that a less-gilded recollection of Merckx’s era is taking hold. Of some riders this is true, and new truths emerge in The Cannibal – one in particular from Martin van den Bossche, the Faema teammate Merckx attacked before the summit of the Tourmalet on that memorable day in the Pyrénées in the 1969 Tour. For other riders, though, the past is just getting more gilded, with an even more golden light shining on it: when Johnny Schleck (father of Fränk and Andy) raced alongside Ocaña in the seventies Merckx was le grand con, today he has become le grand. Friebe is alive to this, referencing incidents where he is aware his interviewees may be gilding the lily, maybe being a little bit diplomatic (Merckx still wields considerable power in our sport). Ultimately, then, it is up to others to strip back some of the gilt and show the lead that lies beneath. And this is where those who chronicle Merckx’s era enter the equation. This is where they, in particular, need to pay proper heed to the role doping played in our sport back then.

When it comes to doping, Friebe takes an adult aproach to the subject, not hiding it (the first reference to the subject appears on page three) but rather discussing it a frank manner. Merckx came along just as the sport was taking its first tentative, half-hearted steps toward cleaning itself up. He arrived as cycling was moving out of what Pierre Dumas – the Tour’s doctor and an early champion of the struggle to clean up sport – called ‘the semi-scientific era,’ and into an era more and more governed by science. Cortisone arrived in the late sixties (though it wasn’t banned until the late seventies and couldn’t be tested for until the late nineties), and Jacques Anquetil made no secret of the super-ozone therapies he underwent in the late sixties, while blood-doping became a part of all sports, even cycling, as early as the seventies.

From early in his career rumours of doping surrounded Merckx, rumours as laughable as most of the stories you’ll read in The Clinic immediately following a surprise victory today: Merckx must have had access to some secret rocket-fuel that was undetectable; Merckx was using a mystery Mongolian plant extract. Such rumours can be dismissed. But they shouldn’t ignored. They help show the sway doping held over the peloton, that it has always been an arms race, that some riders have always suspected their rivals of having something they, too, wanted to get hold of.

Friebe considers the post-EPO rose-tinted view of that era’s doping – an era, we’re supposed to believe, of pop-guns compared to the howitzers that came along later – and considers the question of how, or whether, doping contributed to Merckx’s impressive palamarès. His conclusion will probably end up pleasing few – neither those who prefer to air-brush the subject from history, nor those who want to wipe from history everyone who ever dabbled with anything on the banned list – but seems to me to be a fair appraisal of the known facts.

The Cannibal is not without its faults. A few tpyos [sic] which its editors should have picked up have slipped through [You’re one to talk! – ed.], Friebe’s dislike of the Col d’Éze – which he unconscionably omitted from his Mountain High – is now stretched to calling it the Col de la Turbie (what he has against this little bit of Ireland on the Côte d’Azur I don’t know), and the book lacks an index, which serves to makes life hellish for people like me who mine such books for stories. To be fair, though, most of these quibbles I didn’t notice on my first read, and only saw the second time round.

Why? Because The Cannibal is a fun and engaging read. Friebe races along at thriller pace, but still has time to notice the symbolism of the gladioli to be found in the hotel reception that Monday morning in the 1969 Giro, or drop in comedy moments like Roger de Vlaeminck demonstrating how to mop up spilled coffee (‘Dab! Dab, don’t wipe. Dab.’). By sitting back and acting as choir-master to the massed voices of his interviewees, Friebe allows them to tell the story in their own words. Even when he’s talking as himself, Friebe is using the voices of others, echoing, for instance, Dino Zandegù’s reference to Merckx’s team-mates as ‘Ven Den this’ or ‘Van Ben that’ (as the ghost in the machine for Mark Cavendish’s biography, Boy Racer, I guess Friebe has to be alive to the language used by others). What you get from all this is a book that’s up there with Richard Moore’s Slaying the Badger and Laurent Fignon’s We Were Young and Carefree: a book not just for die-hard cycling fans. A book that reads like a novel.

What to make, then, of the portrait of Merckx we’re left with by the last page of the book? Friebe’s Merckx is imperfect – this no God sent among us, to show a better way and be idolised. Rather he’s a man like everyone else: an outstandingly gifted athlete who was at times fragile, at times supremely confident; a man who was at times still a child, loving his sport; and at times a cold, hard despot surrounded by lieutenants who ruled with an iron fist. He’s like a lot of the people he rode with and against. But at the same time, he’s different: both Italo Zilioli and Louis Ocaña shared Merckx’s mental fragility, as did a lot of other riders, but somehow – unlike them – Merckx turned weakness into a strength.

Friebe’s portrait of Merckx is one of light and shade, one that helps to redefine Merckx for a twenty-first-century cycling audience. An audience not necessarily in thrall to a rose-hued portrait of the past, but at the same time one which knows that it is actually true – compared to today it was all a lot harder back in Merckx’s day. Not necessarily better. But definitely different.

* * * * *

Danel Friebe’s Eddy Merckx – The Cannibal is published by Ebury Press (2012, 344 pages).

1 Comment

[…] Eddy Merckx – The Cannibal is published by Ebury Press (read our review). […]