He is half-man, half-bike.”

~ Lucien Bodard

It could have all been so very, very different.

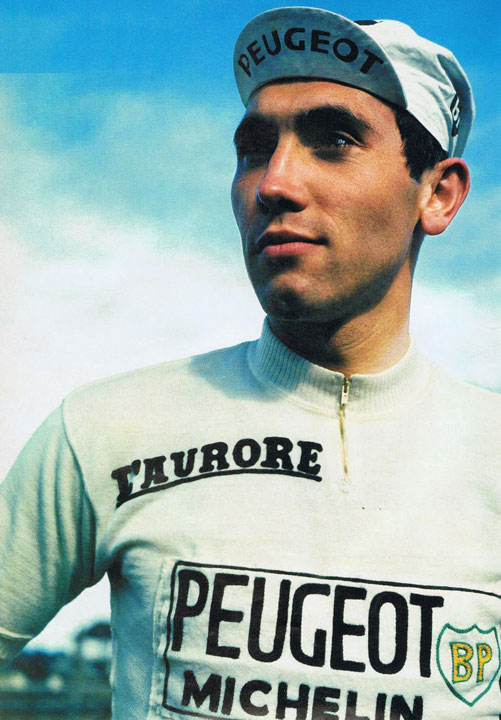

Ward Merckx was born on June 17, 1945, in the Belgian village of Meensel-Kiezegem, south-east of Brussels, in the heartlands of the Brabant. A Flanders boy, born and bred. A strong junior, when he moved up to the pro ranks it was in the service of Rik van Looy. A member of the Red Guard, a disposable sprint train component, his role nothing more than to deliver his leader to the sprint zone and then fade away. After a brief stint in France, with Peugeot, Ward Merckx returned to Belgium, where he served a string of Flandrian lions, up-and-coming stars of the future from Roger de Vlaeminck to Freddy Maertens, ending his career helping the young Sean Kelly learn the secrets of la métier. No books have been written about Ward Merckx and his is not a name recalled by many. For most he’s just another Jos Bruyère or Ronny Onghena, one of the many whose careers were dedicated to being spear carriers for the stars of their day. But some in Belgium today think of Ward Merckx as the one that got away. They wonder what place in cycling he could have carved out for himself if he’d just given his all to himself and not to others. If he’d just broken away and carved out his own career.

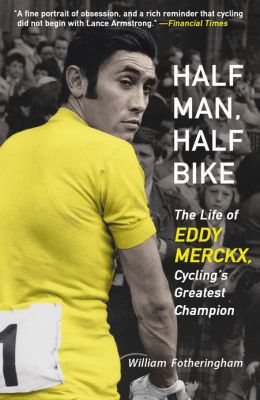

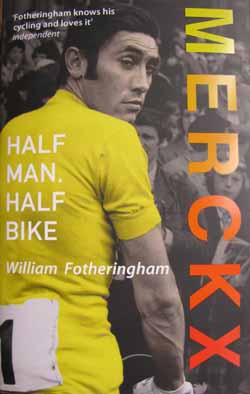

It wasn’t like that, though. And understanding how the boy who was born Edouard Merckx grew up to become Eddy instead of Ward – grew up to become a robotised half man, half bicycle – is one of the key strengths of William Fotheringham’s Merckx: Half Man, Half Bike. At the heart of that explanation is the split within Belgium between Flanders and Wallonia, a split which is probably best exemplified by Belgium’s most famous bike race, the Ronde van Vlaanderen, the Tour of Flanders.

In his Fausto Coppi biography, Fallen Angel (Yellow Jersey Press, 2009) Fotheringham noted how the Giro d’Italia – not unlike the Tour de France and the Vuelta d’España – became a symbol of national unity. In Half Man, Half Bike Fotheringham this time notes how the Ronde is a symbol of national disunity, of regional separateness. And while Merckx was Flanders born and is a two-time winner of the Ronde, he is no Flandrian. By virtue of his parents having moved from Meensel-Kiezegem to Woluwe-Saint-Pierre – having moved from the heart of the Brabant to the suburbs of Brussels, having swapped their working class roots for a middle class life, having swapped Flemish for French – Merckx became an assimilated Walloon, one who tried to site himself above either regional identity and set himself as a symbol of unity in a disunited country.

Fotheringham’s explanation of the role regional identity plays in Belgian cycling leaves the reader looking forward to a project the author hints at in his introduction to Half Man, Half Bike, research he has been undertaking for a future book on Flandrian cycling. There is, though, something in the way Fotheringham handled this subject that leaves you feeling that Half Man, Half Bike is an offshoot of a greater project, and consequently that little bit weaker for that.

Fotheringham is, it ought go without saying, an experienced commentator on our sport: he has written the book on Tom Simpson, Put Me Back On My Bike (Yellow Jersey Press, 2001). His chronicle of the British contribution to the Tour de France, Roule Britannia (Yellow Jersey Press, 2001), is brilliantly researched and wonderfully told. And his Coppi biography went far beyond the usual guff written about il campionissimo in the capsule biographies to be found in other books or which appear in cycling magazines with the regularity – and illumination – of eclipses.

That Coppi biography offers some good points of comparison with this biography of Merckx. The subtitle of the former – The Passion of Fausto Coppi – could equally be used for Half Man, Half Bike. When interviewed by Fotheringham in 1997 Merckx answered the question of why – why the years of focus? why the need to win so often and so much? – with a simple soundbite: “Passion, only passion.”

In his Coppi biography Fotheringham took two very different images of the Italian champion of champions, one from early in his career and one from later, and asked how Coppi went from one to the other. Here the question Fotheringham seeks to answer is the one Merckx has explained away as being all down to passion: why? Merckx’s answer obviously needs explication, the soundbite needs to be explored in greater depth. So Fotheringham adds another question: how did Merckx become the greatest?

The “how” allows Fotheringham to identify key moments from Merckx’s career. As well as the oft told tales from the Tour – tales which are told and retold in most of the capsule biographies of Merckx that have appeared down through the years – Fotheringham also talks about many of the other races that help illuminate Merckx’s character. One of the strengths of Half Man, Half Bike is that it contains a lot of racing action, drawing fully from a palmarès that contains notches for just about every important race on the calendar. It moves the story beyond the overly familiar Tour-centric version so often told in the capsule biographies. The depth and breath of Merckx’s palmarès, though can itself be problematic for any biographer of Merckx: space is limited. Fotheringham himself acknowledges this problem:

Capturing the essence of such a visual, sporting and human icon poses particular issues for a journalist. Ours is a reductive art: stripping what we are presented with to an immediate bite. The issues have to be explored within a limited window of time. You can’t cover them all.”

This, at times, can leave the telling of the tale somewhat matter of fact. Interviewees are reduced to soundbites, stripping some of the depth from the tales they have to tell of Merckx. My own personal preference in such things is for the author to allow his interviewees to speak, even when they go off piste and don’t seem to be talking directly to the topic. As a rule, it is the men and the women who were there and saw things firsthand who I want to hear from. My own personal preference in such things is for the author to act more as a choir master, shaping many voices into a greater whole.

Fotheringham does quote extensively from secondary sources – contemporary journalism from the likes of Marc Jeauniau and Geoffrey Nicholson and other biographers of Merckx, such as Théo Mathy, Jean-Paul Ollivier and Roger Bastide – but, by and large, the dominant voice in Half Man, Half Bike, is that of Fotheringham himself. For me, giving the interviewees the space in which to breathe, to tell the story in their own words, would have added colour to the tale, even if that would have required a bigger canvas or a reduced focus on particular events in Merckx’s riding career. At the same time, having borrowed from a quote about a robotised Merckx perhaps there is method to Fotheringham’s manner: colour would only humanise Merckx.

Fotheringham – like many others – has placed Merckx on a pedestal. The Merckx story, he says, is about competition pure and simple. Try to tell the lives of Coppi, of Jacques Anquetil or of Lance Armstrong and you must necessarily also talk about the women, the drugs, the cancer. With Merckx, we’re told, it’s all about the bike:

A lack of ‘reason’ is the only side to Merckx, whose story was described by the French writer Philippe Brunel as ‘a vocation fulfilled in exemplary style.'”

In order for that to be true, though, certain parts of the Merckx story need to be, well, tidied up. And here comes my main disagreement with the manner in which Fotheringham tells Merckx’s story: in short, he takes a bucket of whitewash to Merckx’s use of performance enhancing drugs.

Merckx tested positive during his career on at least three occasions: the 1969 Giro d’Italia, the 1973 Giro di Lombardia and the 1977 Tour of Belgium. Only two of those cases are discussed in Half Man, Half Bike. The first – Savona – is well known. Fotheringham’s view is simple: the tests were illegal, therefore Merckx was innocent. The second – Lombardia – is explained away by an experienced team doctor (the same Angelo Cavalli who carried out the tests at Savona four years earlier) not knowing that a cough medicine he prescribed for Merckx contained ephedrine. Having explained away both of those cases – and thus left the reader with the impression that Merckx rode à l’eau – Fotheringham barely even alludes to the third fail, Merckx’s 1977 Stimul bust at the Flèche Wallonne.

For me, as I have said elsewhere, such matters matter. Acknowledging that Merckx didn’t always play by the anti-doping rules doesn’t mean that you invalidate any of his more than 500 victories. It merely acknowledges the reality of his era, the reality of our sport. And the reality is that Merckx, while undoubtedly a superior cyclist both in terms of his physical and mental strength, was not unlike most of his peers. Alas, unlike greats that came before him, unlike Coppi and Anquetil, this aspect of Merckx’s riding career is something that he – and far too many of the people who write about him – would prefer to airbrush from history.

Does this invalidate everything else within Half Man, Half Bike? As with the impact on Merckx’s palmarès of his use of doping the answer is obviously no. But the manner in which Merckx’s doping record has been wiped clean tells you something about the story Fotheringham has spun about the man. Having declared Merckx to have been exemplary, facts have been marshalled to support that declaration, inconvenient truths ignored where they show that the fulfilment of Merckx’s vocation was not quite as ideal as some would like to suggest it was. But isn’t that the way all biographies are written? What then is the real problem here? Théo Mathy – the Belgian journalist who was in that hotel room in Savona when Merckx was ejected from the 1969 Giro, and who has chronicled Merckx extensively – said of his compatriot one time that he is a prisoner of his legend. Maybe the real problem with Half Man, Half Bike is that it fails to move beyond the legend and see the man hidden beneath.

* * * * *

William Fotheringham’s Merckx: Half Man, Half Bike is published by Yellow Jersey Press (2011, 308 pages).

2 Comments

[…] Cyclismas: Last year we had three books about the Giro all arriving within a few weeks of one and other, this year we get two Merckx books. I guess it must have been a bit of a surprise when you realised that William Fotheringham was also working on a Merckx biography. […]

Merckx dominated in the worst doping era ever, the seventies.

Synacthen Direct, Celestone to get the system working again and nandrolone every month. On top of that, to get the ‘moral’, they did amphetamines. Hormones were classified and authorized as vitamins untill 1978.